Big Red Book

Celebrating television's This Is Your Life

22 November 1975

a brief biography

The Legend That Was Eamonn Andrews

a celebration to mark the presenter's centenary year

'Some people can't cope with being a superstar. But Eamonn, it's as though it's his divine right'

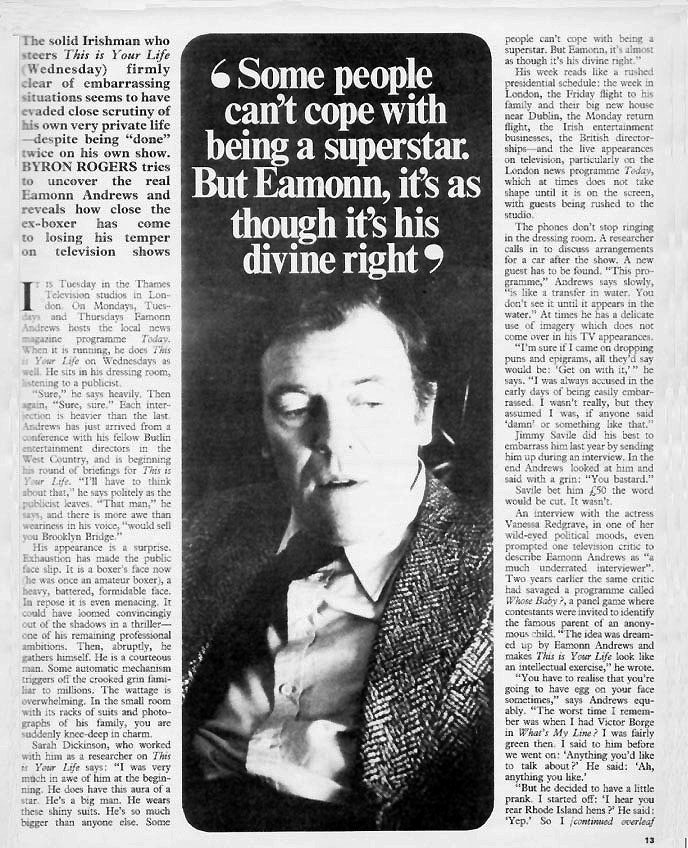

The solid Irishman who steers This Is Your Life (Wednesday) firmly clear of embarrassing situations seems to have evaded close scrutiny of his own very private life – despite being "done" twice on his own show. BYRON ROGERS tries to uncover the real Eamonn Andrews and reveals how close the ex-boxer has come to losing his temper on television shows.

It is Tuesday in the Thames Television studios in London. On Mondays, Tuesdays and Thursdays Eamonn Andrews hosts the local news magazine programme Today. When it is running, he does This Is Your Life on Wednesdays as well. He sits in his dressing room, listening to a publicist.

"Sure," he says heavily. Then again, "sure, sure." Each interjection is heavier than the last. Andrews has just arrived from a conference with his fellow Butlin entertainment directors in the West Country, and is beginning his round of briefings for This Is Your Life. "I'll have to think about that," he says politely as the publicist leaves. "That man," he says, and there is more awe than weariness in his voice, "would sell you Brooklyn Bridge."

His appearance is a surprise. Exhaustion has made the public face slip. It's a boxer's face now (he was once an amateur boxer), a heavy, battered, formidable face. In repose it is even menacing. It could have loomed convincingly out of the shadows in a thriller – one of his remaining professional ambitions. Then, abruptly, he gathers himself. He is a courteous man. Some automatic mechanism triggers off the crooked grin familiar to millions. The wattage is overwhelming. In the small room with its racks of suits and photographs of his family, you are suddenly knee-deep in charm.

Sarah Dickinson, who worked with him as a researcher on This Is Your Life says: "I was very much in awe of him at the beginning. He does have this aura of a star. He's a big man. He wears these shiny suits. He's so much bigger than anyone else. Some people can't cope with being a superstar. But Eamonn, it's almost as though it's his divine right."

His week reads like a rushed presidential schedule; the week in London, the Friday flight to his family and their big house near Dublin, the Monday return flight, the Irish entertainment business, the British directorships – and the live appearances on television, particularly on the London news programme Today, which at times does not take shape until it is on the screen, with guests being rushed to the studio.

The phones don't stop ringing in the dressing room. A researcher calls in to discuss arrangements for a car after the show. A new guest has to be found. "This programme," Andrews says slowly, "is like a transfer in water. You don't see it until it appears in the water." At times he has a delicate use of imagery which does not come over in his TV appearances.

"I'm sure if I came on dropping puns and epigrams, all they'd say would be: 'Get on with it,'" he says. "I was always accused in the early days of being easily embarrassed. I wasn't really, but they assumed I was, if anyone said 'damn' or something like that."

Jimmy Savile did his best to embarrass him last year by sending him up during an interview. In the end Andrews looked at him and said with a grin: "You bastard."

Savile bet him £50 the word would be cut. It wasn't.

An interview with the actress Vanessa Redgrave, in one of her wild-eyed political moods, even prompted one television critic to describe Eamonn Andrews as "a much underrated interviewer". Two years earlier the same critic had savaged a programme called Whose Baby? a panel game where contestants were invited to identify the famous parent of an anonymous child. "The idea was dreamed up by Eamonn Andrews and makes This Is Your Life look like an intellectual exercise," he wrote.

"You have to realise that you're going to have egg on your face sometimes," says Andrews equably. "The worst time I remember was when I had Victor Borge in What's My Line? I was fairly green then. I said to him before we went on: 'Anything you'd like to talk about? He said: 'Ah, anything you like.'"

"But he decided to have a little prank. I started off: 'I hear you rear Rhode Island hens?' He said: 'Yep.' So I asked him: 'Do you like doing that?' 'Nope.' And so it went on. It would have been funny for 30 seconds, not so funny for 60. After two minutes it wasn't funny at all. I had to wrap it up in the end. But I had to keep laughing."

"I had a bit of it with the American actor Michael J Pollard, and with Andy Warhol. 'Yup. Nope.'" He says the words with bitter emphasis. "You start off in interviews like that by trying to survive. You think it'll end. But it's like pushing your face into sponge." Again, the sudden, accurate image.

"You have to avoid being desperate. I've often thought about what could happen, and about hitting somebody. Your mind is rushing around in a cage. But I don't easily get annoyed. I don't think I've ever got properly annoyed. A boxer who gets annoyed gets his head knocked off. But Borge came closest to annoying me," he says with emphasis.

"I think Eamonn realises after 20 years that a person who takes sides on television gets into pretty deep water," is the viewpoint of Thames current affairs executive producer, Andy Allan.

Andrews' is a peculiar career. It depends on the fact that somewhere there must be a limitless reserve of people, ready to come forward, to be interviewed, and then to disappear. "People ask me what so and so was like. The answer is that some of the time I only saw him for as long as they did. You see him for a second, then he's gone."

As an interviewer Andrews is the professional, the grin on the old stone face, calm. But in This Is Your Life he is the superstar. He brought the programme from America to the BBC and then to ITV.

"In This Is Your Life everything is geared around him," says Sarah Dickinson. "Around him and his green felt pen. He has the veto. But he's a very good editor. He usually knows."

It is ironic seeing this slightly weary figure and remembering his own account of the insistent ambition which brought him to the business in the first place. A carpenter's son, he was working in an insurance office in Dublin and, at the same time, pestered Radio Eireann for a job. His persistence was eventually rewarded, partly because as an amateur boxer he had plenty of opportunities to interview the great boxing stars. But all the while he kept up a barrage of letters to the BBC. He wrote in his autobiography: "If anyone analyses the BBC archives I am sure that under the heading of unsolicited correspondence they will find more letters from E. Andrews of Dublin than any other pair of individuals."

But it succeeded. He was appointed as a radio commentator and the road towards What's My Line? and This Is Your Life was open to him.

"What am I?" asks Andrews, "I don't know how to describe myself. This comes up every time I have to fill in a form. I put down 'television commentator'. Or I scribble 'TV' so they can't read it. I went to a casino in Bordeaux once and did that. When I came back I found they'd filed me as an electrician."

Talking to him is not easy. There are certain things he will not talk about. Money is one. "I've never talked about money with producers. I let others do that. It means I can concentrate on discussing the programmes. It's not very adult to talk about money." He shrugs, embarrassed.

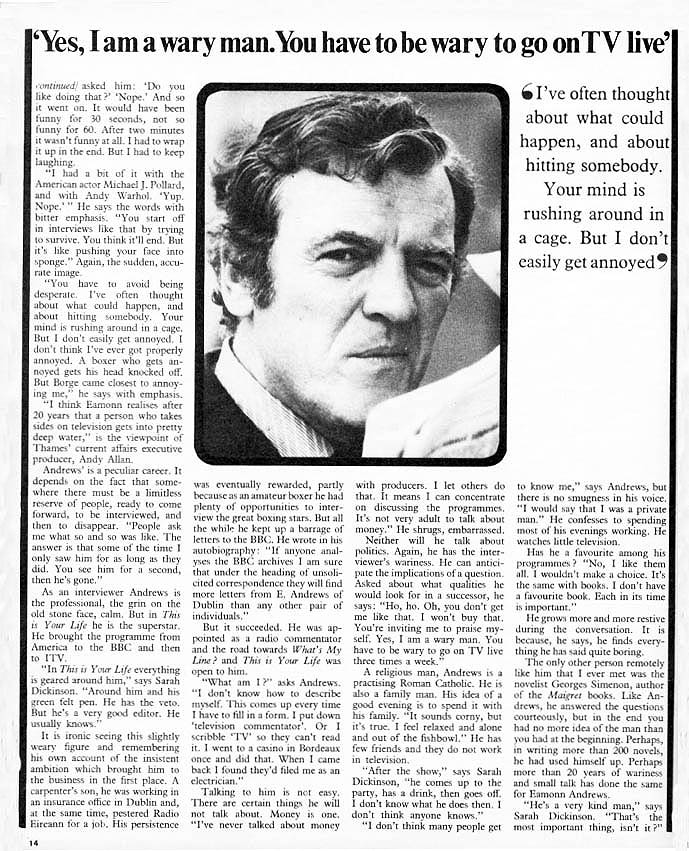

Neither will he talk about politics. Again, he has the interviewer's wariness. He can anticipate the implications of a question. Asked about what qualities he would look for in a successor, he says: "Ho, ho. Oh, you don't get me like that. I won't buy that. You're inviting me to praise myself. Yes, I am a wary man. You have to be wary to go on TV live three times a week."

A religious man, Andrews is a practising Roman Catholic. He is also a family man. His idea of a good evening is to spend it with his family. "It sounds corny, but it's true. I feel relaxed and alone and out of the fishbowl." He has few friends and they do not work in television.

"After the show," says Sarah Dickinson, "he comes up to the party, has a drink, then goes off. I don't know what he does then. I don't think anyone knows."

"I don't think many people get to know me," says Andrews, but there is no smugness in his voice. "I would say that I was a private man." He confesses to spending most of his evenings working. He watches little television.

Has he a favourite among his programmes? "No, I like them all. I wouldn't make a choice. It's the same with books. I don't have a favourite book. Each in its time is important."

He grows more and more restive during the conversation. It is because, he says, he finds everything he has said quite boring.

The only other person remotely like him that I have ever met was the novelist Georges Simenon, author of the Maigret books. Like Andrews, he answered the questions courteously, but in the end you had no more idea of the man than you had at the beginning. Perhaps, in writing more than 200 novels, he had used himself up. Perhaps more than 20 years of wariness and small talk has done the same for Eamonn Andrews.

"He's a very kind man," says Sarah Dickinson. "That's the most important thing, isn't it?"