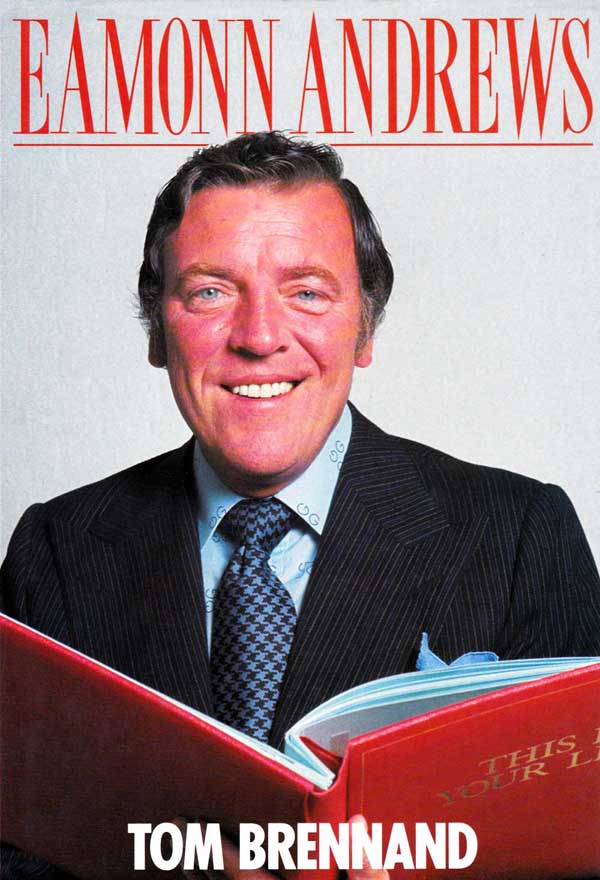

Big Red Book

Celebrating television's This Is Your Life

a brief biography

The Legend That Was Eamonn Andrews

a celebration to mark the presenter's centenary year

the programme's icon

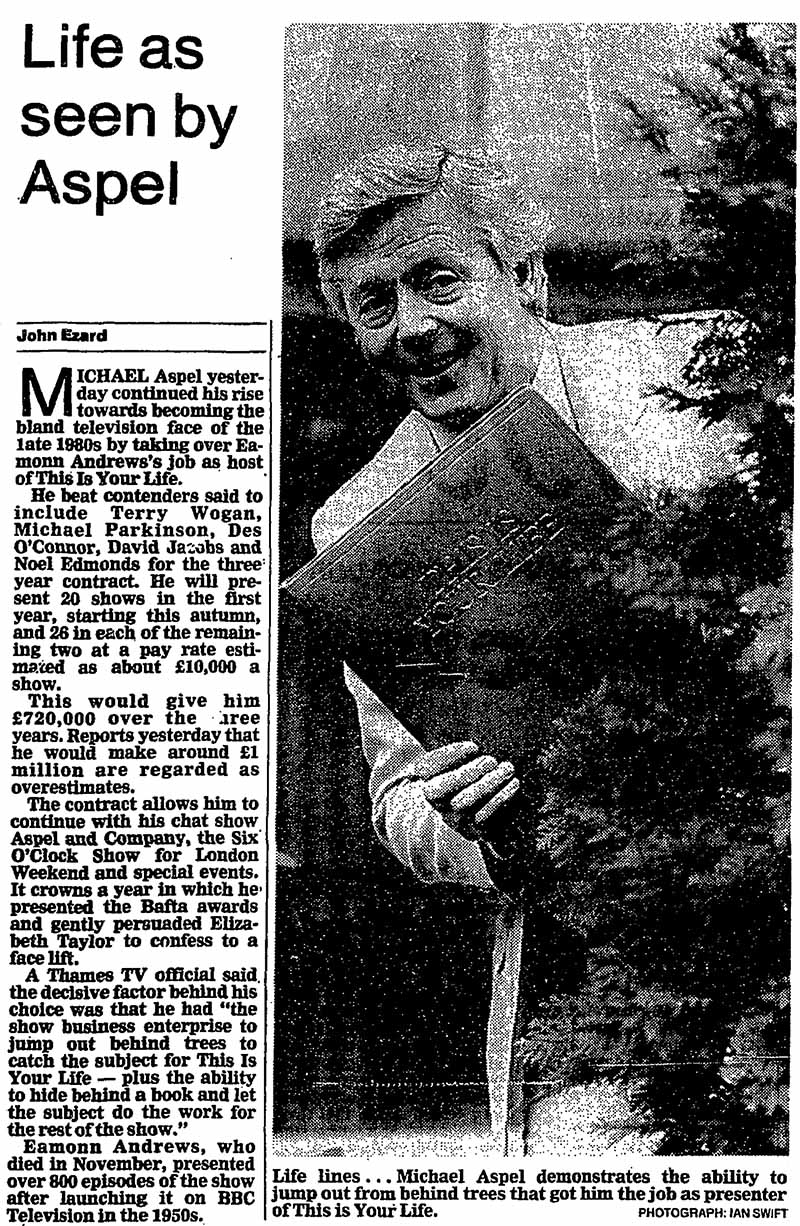

The Sunday Times 26 March 1989

Books: An attempt on his life: 'Eamonn Andrews' by Tom Brennand

BYLINE: CRAIG BROWN

Seventeen years is probably a little too long to spend as principal scriptwriter on This Is Your Life.

In Tom Brennand's case, the damage is gruesomely evident. Whirling around for 17 years in a weightless vacuum of heartfelt tributes, long-lost friends and tearful reunions, he was bound to feel dizzy at the end of it all, and now he has been sick. Every hue and shade of loathing, bottled up for so long, is pressed between the pages of this book. He loathes Eamonn Andrews, of course, and he loathes almost everyone Andrews ever met, and he loathes everything to do with television and entertainment, and he seems to loathe the English language, but the very special kind of loathing that seeps through every paragraph of this curious biography is the loathing Tom Brennand feels for himself.

But first, since it is the ostensible subject of the book, let us examine Brennand's loathing of Andrews. He believes Andrews to have been incompetent, lazy, drunken, vain, asexual, social-climbing, penny-pinching, fraudulent, heartless and autocratic. He gives a little bit of evidence for each of these accusations. Incompetent? Well, he once called Gloria Hunniford 'Gayle Hunnicutt', quite apart from the fact that when his team was talking about Harry H Corbett from Steptoe and Son he thought they were talking about Harry Corbett, the Sooty puppeteer. Lazy? Well, he 'had never grown to accept that watching television was part of the price that had to be paid for appearing on it'. Asexual? Well, 'in the 22 years I worked closely with Eamonn, I never once heard him mention sex'. Penny-pinching? Again, the evidence seems underwhelming. 'Doubtless it was a genuine oversight when, in 1971, he failed to pay his £50 annual subscription to the Royal Mid-Surrey Golf Club... but it was a fact that he washed his own hair before visiting the barber to save paying for a shampoo, and, besides putting optics on his spirit bottles... he also smoked a cheap brand of cigarettes because the makers sent them to him free.'

Having spent the greater part of his life as a television writer huffing and puffing to blow the most meagre gestures into lavish acts of bountiful kindness, Brennand is now determined to reduce every humdrum habit to a sticky puddle of squalid pettiness. Even what Brennand acknowledges as Andrews' 'ability to inspire loyalty, often a sympathetic loyalty, from his staff' is presented as 'part of his native guile'.

Had the publishers of this creepy book presented it not as a biography but as a novel in the tradition of Pale Fire, with the crazed narrator wreaking revenge on his dead subject, it might well have become a cult classic of humour. Just as Andrews seemed to exhibit the humanity of a bumbling, sweating, hard-slogging everyman, Brennand is a sort of diabolic nonentity, a black-sheep brother of Mr Pooter. 'Companions on anything but the shortest of journeys found it hard work keeping a conversation going as he contributed so little and frequently 'dried up' completely,' writes Brennand. Given that the broad term 'companions' must surely mean Brennand himself, one can begin to see things from Andrews' point of view. Would any sane person wish to be stuck with Brennand on a long journey and, if stuck, would they say anything other than the bare minimum? Brennand feigns disgust as he reveals deceits perpetrated by This Is Your Life: the red book was full of blank pages (gosh!), any unpleasantness was eradicated from celebrity biographies (gasp!), one or two subjects were in on the secret (golly!) while contriving to forget that, as he is happy to boast elsewhere, for a full 17 years he was 'programme consultant and principal scriptwriter' of the show. This means that heavily sarcastic sentences such as, 'The writers naturally believed what they had written was a vast improvement on the guests' own ideas on what the truth of the matter was' can be aimed at no one quite as certainly as himself.

Those of us who thrive on the comings and goings of bottom-drawer celebrities will be able to find a few dribs and drabs of honest-to-goodness tittle-tattle beneath all the tut-tuts of Brennand's spurious moralising. Angela Rippon, for instance, listed all the people who should have been on her This Is Your Life without realising that most had been approached and declined, and Zsa Zsa Gabor paid tribute to Eric Sykes without being able to remember who on earth he was, and plans for a programme on Michael Winner were abandoned when they couldn't find enough friends, but, really and truly, there isn't much else.

The comic possibilities of a gravel-hearted misanthropist spending a lifetime scripting This Is Your Life finally fall flat simply because the book is so badly written. Ironically this, ironically that: Brennand shares the belief with most disc jockeys and sports commentators that 'ironically' is merely a synonym for 'here's another uninteresting detail' or 'another tiny coincidence coming up'.

The Stage 10 August 1989

Eamonn Andrews, by Tom Brennand (Weidenfeld and Nicholson, £12.95).

It does not seem long since those of us who were preparing obituaries of Eamonn Andrews were using such phrases as "the greatest broadcaster of our time". It is just as well that no one consulted his close associate for many years Tom Brennand, who does a demolition job on everybody's favourite Irishman.

So far from being a man whose easy charm made him get on with everybody, Andrews actually had a fear of human contact. So far from being able to ad lib his way out of crisis, he had to go before the cameras fully briefed or else he wouldn't go on at all. So far from personally knowing all the great, famous and good he interviewed during his career, he deliberately kept himself apart from them.

The book therefore does no favours to Andrews' memory and is doubtless monumentally unfair. But if even only half of what Brennand asserts is correct, there is something vaguely worrying that somebody as ill-equipped as Andrews for the ordinary setbacks of life should have been manufactured by television into a greatly loved figure. It is not that behind the scenes he may have been a tyrant – which one does not honestly think he was – but that someone who combined gracelessness, a certain meanness and a fair degree of ignorance could reach such heights, though even Brennand pays tributes to his sports reporting.

This is a book which in my opinion should not have been published so soon after Andrews' death. In this instance what might be the truth leaves a nasty taste in the mouth.

Peter Hepple