Big Red Book

Celebrating television's This Is Your Life

Eamonn Looks Back

"The 'Life' gave me some of the most wonderful, touching and exhilarating moments I ever had on television. It made life-long friends for myself and the team because, when the show is taken in the spirit it is meant, it is a unique and touching experience for the recipient... the programme is a tribute, a salute, a happy party surprise, a nod of gratitude from a community well-served..."

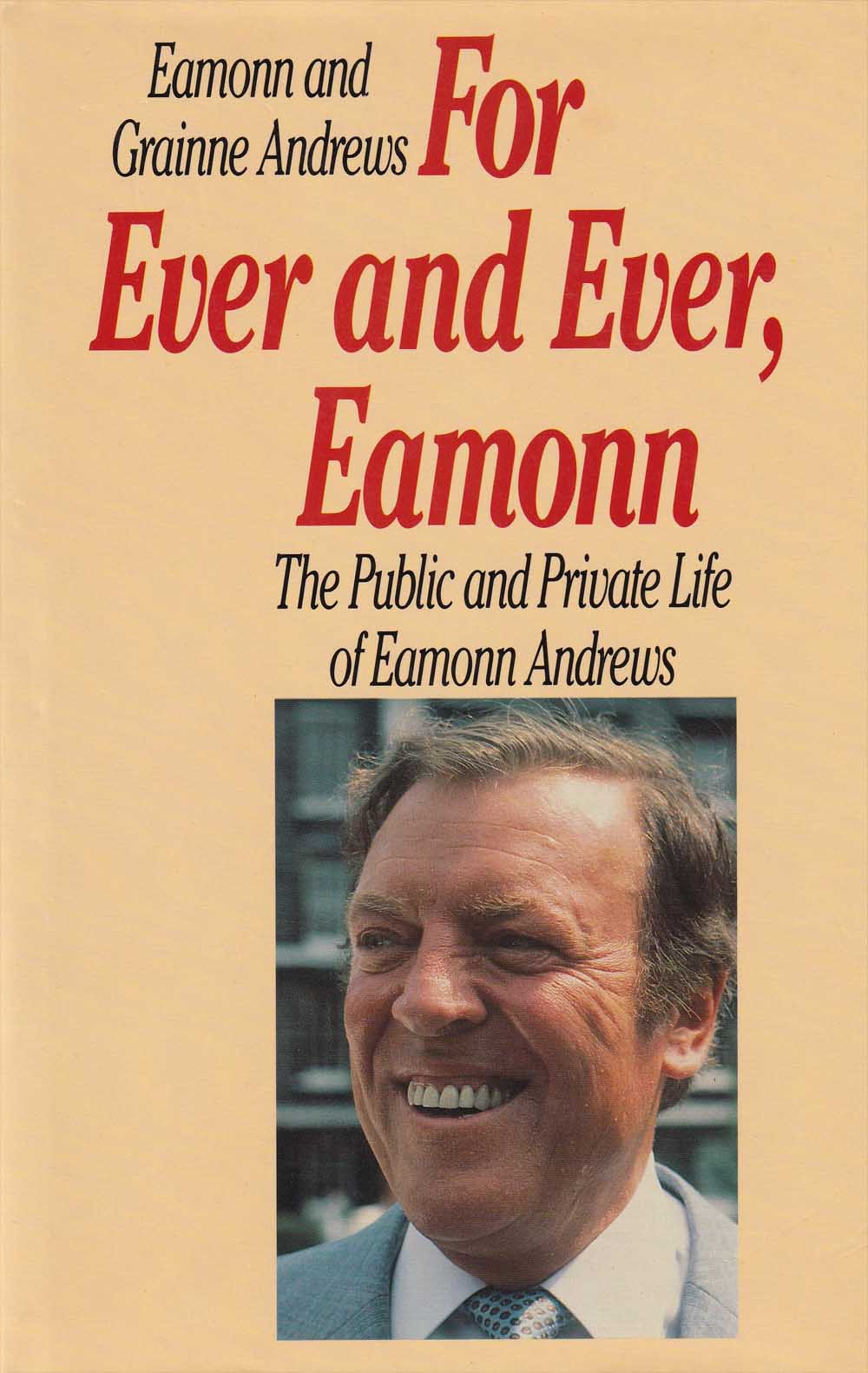

Before his sudden death in November 1987, Eamonn Andrews was writing the story of his forty-year radio and television career - the rise of a £5-a-week insurance clerk to Britain's highest-paid performer. He didn't get the chance to complete that story.

However, Eamonn's wife, Grainne, finished the story for him, and the book was published in 1989 as For Ever and Ever, Eamonn.

In Eamonn's own words, here are some extracts recalling some of the milestones in the history of This Is Your Life...

related pages...

a brief biography

tributes to the original presenter

a brief biography

the producers who steered the programme's success

the show's fifty year history

the genesis of the programme

the man who created it all

those who said 'No'

Snoopers on TV? Not on your life!

The Daily Express reports on an American import

Radio Times previews the first edition

The Manchester Guardian reviews the first edition

Press coverage of the footballer's refusal to participate

It's the show that balances on a tightrope

TV Times interviews footballer Danny Blanchflower

When I tuned into This Is Your Life on American television, my first reaction was: this is television. I thought the creator and presenter, Ralph Edwards, had pulled out too many stops and coloured too many purples, but I felt we could pitch it right for British audiences. I cabled Ronnie Waldman, telling him I'd love to do it at home.

Later, Ronnie told me that the BBC governors (why they were consulted, I never knew) recoiled from the formula as being very un-British, too sentimental and 'all-that-tosh-you-know'. All they would agree to, under Ronnie's gentle pressure, was to give it a trial on a monthly basis. If it didn't work, it could be dropped from the schedules without too much trouble.

Ralph Edwards and his production team travelled to London to launch the British version of This Is Your Life

A number of suggestions were made for a possible opening subject and finally it was decided to surprise the great footballer, Stanley Matthews, who was riding high on one of his many crests of popularity.

Most of the preliminary investigations and contacts had been made by the time Ralph Edwards and his mini-team arrived here. When I say mini-team, the outstanding member of it, in fact, was very maxi. He looked like a bear, in so far as any human being can. He was tall and soft and paunchy and spoke in a kind of European growl. His name was Axel Gruenberg. We talked with him a lot and found him a kind and gentle and helpful colleague, unlike the sharp-shooters we'd been warned to expect. He had one astonishing trait. He started to tell us about one programme in particular that Ralph had done.

He recalled a touching confrontation and what it meant to the story, and as he talked I didn't know where to look. Tears were rolling down his face. A sob was chugging at his voice. He took out a handkerchief almost as big as himself, wiped away the flow and apologised. This was to happen several times. Ralph was not at all surprised when I told him about it.

'Yes,' he said. 'Quite a problem that at times. His production assistant has had to take over once or twice when Axel's glasses got so steamed up he couldn't see the action.'

What a lovely, lovely man. I went to see him in Hollywood many years later, after he'd retired, and it was the same old story: the eyes filled, the glasses steamed and the voice wobbled and we had a wonderful time.

Everything was going to plan. There was great pre-publicity about the new programme and Ralph called what was to be the final meeting on the Wednesday before the Monday transmission – live, of course. [Bigredbook.info editor: the first edition was actually broadcast on a Friday] When we arrived at his apartment in ye olde worlde St James's all hell broke loose. Someone on the Daily Sketch tabloid newspaper had leaked the story that Matthews was to be the first subject for This Is Your Life. Stanley was up in the Lake District fishing, unaware of the hullabaloo, and Ralph wondered if we could see to it that he didn't see the offending paper. We had to remind him that our newspapers were national rather than local; and that, in any event, there would be no way of protecting Stanley from the casual comment of a fellow-fisherman, or a neighbour when he returned from his trip. The time left was shatteringly short and heads were put together immediately to think of a story that could be presented quickly.

At this point, I had a personal dilemma: I was writing an overnight column for the Star, a London evening paper, and had led my story with a piece about Ralph Edwards and This Is Your Life's debut. By now, the first edition was already on the streets and, in view of the Matthews situation, I needed to update the story. I asked to be excused from the meeting to telephone the Features Editor and redraft the column. I was some time, and when I rejoined the meeting, I sensed a coolness. It dawned on me that the Americans in the party had probably thought everyone working for Fleet Street must be tarred with the same brush; that I was no longer a good risk, so to speak. It seemed a bit wild, but all the more likely when they said they had decided to head up to Television Centre to see Tom Sloan, then boss of Light Entertainment, to see what new plans they could put into action. They said they would contact me later.

I really did feel hurt. What I didn't know was that, while I'd been on the telephone, someone had pointed in my direction and mouthed the possibility of doing me! There were two obvious reasons: one, I was available on the night; and, two, that most of the people I knew could probably be rounded up in a hurry. The big problem now was to get rid of me, which they did, of course. I went home to Maitland Court for lunch and was soon cheered up with a call from Television Centre to say they'd come up with a smashing subject for the programme: Freddie Mills, the former light-heavyweight champion of the world and a very good friend of mine.

Boxer Freddie Mills, involved with the first British edition of This Is Your Life, became a subject in January 1960

What did I think? I said it was a great idea and they suggested that, as a sports broadcaster, I could persuade him to take part in a pilot programme the following Monday. [Bigredbook.info editor: the first edition was actually broadcast on a Friday] If Freddie was free, this would be easy because I knew he was on the look-out for that sort of thing. I told them they should make a formal approach first. They did – and were back to me in a shot to say that Freddie had agreed. This meant I could occupy Freddie all afternoon at Lime Grove Studios while preparation for the programme proper went on in the Television Theatre, round the corner in Shepherd's Bush.

The big snag, of course, was that I would miss seeing how it was all done. However, it was a case of that or no show. Of course, the team had told Freddie all about it and he knew the score... although he did admit later that he started wondering at one stage if he had fallen for a double-double bluff.

I rang Freddie to tell him that, after we'd completed the sports programme, I was going to watch the new This Is Your Life programme; would he like to join me in the audience, where there were to be a number of celebrities, including Ben Lyon and Bebe Daniels and Boris Karloff? He agreed. Of course, he would! I told him we'd drop back between shows to Maitland Court, have a bite to eat and that we'd be collected there and taken straight to the theatre. Poor Grainne was petrified. She had to hide the dress she was going to wear, and pretend she was staying at home and not interested in seeing This Is Your Life that night; she thought the car would never come to take us away. Another car was immediately behind to whisk her round to the stage entrance of the old Empire while we went in the front.

The crowd was moving in as we got there. Suddenly I thought everything had gone wrong. In a corner, I spotted Don Cockell, Britain's former heavyweight champion. Convinced that he was part of the Mills story, I told Freddie to wait inside the door, then I rushed back and hissed in a bewildered Cockell's ear that he wasn't meant to be seen; and to go to the stage door – quick. Poor Don! He must have thought we were all liars on the programme. Here he was, appearing on my show, and he had, no doubt, been told that his appearance would be a big surprise for me. I rushed back to Freddie, hoping he hadn't seen Cockell! We were shown to our seats. The show started.

Ralph Edwards presented the first This Is Your Life book on British television to Eamonn Andrews

Ralph made his introductory remarks and came down into the audience, talking to various celebrities. Then he came to Freddie and me and introduced me to the audience. When he asked me who was sitting alongside me, I said, smugly, that it was, of course, the very popular Freddie Mills. More applause. Ralph gave me The Red Book, and asked me to read what was on the cover.

When I saw it, all I could say – may my Irish ancestors forgive me – was 'Oh, blimey!' There it was under my nose – EAMONN ANDREWS – THIS IS YOUR LIFE!

After that, it was a blur. I couldn't imagine how they had persuaded my mother to fly, much less walk on a stage, but there she was, and my sisters, my brother, my old pals, the amateur drama group I used to help run, one bubbly member, Maureen Wright, being flown all the way from her emigrant home in San Francisco, my old insurance colleague and later international actor, Jack MacGowran, Don Cockell, of course, and Jim Fitzgerald, the lad I'd beaten for the Irish middleweight junior title. [Bigredbook.info editor: there is no reference to members of the drama group being part of Eamonn's tribute in the script or any other documents relating to this edition]

It took me days to recover. It was an experience that would have been worth it at any time. But with me about to do the programme myself, it was gold dust.

The month's trial of This Is Your Life was successful. And the show was on its way to becoming one of the most popular on British television. For the production team involved, it was always a nerve-wracking experience keeping the identity of the subject secret and never a week went by without one drama or another. But the Danny Blanchflower episode takes some beating. It taught me that if I was not to go through life a nervous wreck I should regard the unexpected as the expected.

Northern Ireland international footballer Danny Blanchflower was captain of Tottenham Hotspur FC

When we decided to make the famous Irish International footballer a subject for the 'Life', I was convinced nothing would go wrong. Danny was a radio and TV performer as well as a soccer star and by no stretch of the imagination could I imagine him being averse to publicity. So, when I prepared to spring the surprise on him, I was quite relaxed.

Knowing we had no hope of getting the shrewd Irishman to the Television Theatre without him suspecting something, we arranged for him to go to a different venue, thinking he was doing yet another football broadcast. Without his knowledge, everything would be taped, to be played to the theatre audience and viewing millions half an hour later. A fast car would be waiting to take Danny to the theatre to watch the opening sequence and enjoy all that was to follow.

Danny turned up at the little news studio opposite Broadcasting House all right. And, as a secret camera whirred, I got as far as saying: 'Tonight, Danny Blanchflower, this is your...' But as I was about to present him with The Book, Danny fled like a greyhound from a trap. Angus McKay, the BBC's Sports Editor, lunged forward to try to stop him and caught hold of his coat. But Danny wriggled out of it and rushed through a door and down the stone steps, shouting: 'Let me out. Let me out.'

He was due to play in the Cup Final in a week or two and as I chased after him, I had this dreadful vision of him slipping and breaking a leg. He reached the main exit door safely, thankfully. It was locked. Danny was white and taut. I told him to relax; there were no cameras on him. He didn't want to know, just demanding his coat back. Outside, I tried to persuade him, but his mind was made up: he wasn't doing the programme and that was that. The theatre was full, I said; backstage, many of his friends were waiting to greet him. That was our concern, he said. He hadn't invited them.

I went upstairs and phoned Leslie Jackson to tell him he had no programme. It was a great, great disappointment; weeks of preparation had gone by the board; hundreds of pounds in fares had been wasted – and a theatre full of people now had to be told they could go home.

I couldn't let it go at that without a fight. With just fifteen minutes to go, I went back to the BBC Club where Danny had gone with Angus McKay. Again, I pleaded. Again, Danny refused. Resigned now, I told Danny that a car had been standing by to take him to the theatre; he might as well use it to take him home. But, again, Danny turned down the offer. He was taking no chances, he said. He'd take the tube.

After that, I always expected the unexpected, and never relaxed until the guest of honour was sitting on stage and the programme rolling.

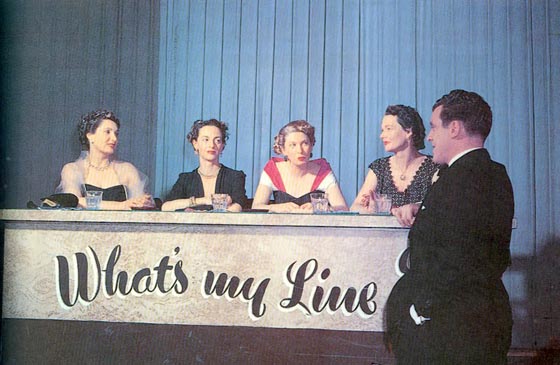

For years, I had been pestering Ronnie Waldman to let me do a late-night talk show along the lines of those in the States which had cleared the way for King Johnny Carson to become an arrogant, smiling, talking millionaire. At one stage, Ronnie told me – in all seriousness – that it would be politic to have such a late-night show in Britain as it might keep the work-force up so late they would not clock in the next morning! Two better reasons, of course, were the runaway success of What's My Line? and This Is Your Life. Since, in addition to these, I was hosting Crackerjack and Playbox, the point was easily made that it would be impossible to do yet another programme, and ridiculous to cancel such winners in favour of the unknown.

Eamonn Andrews was chairman of the panel game show What's My Line? between 1951 and 1963

The opportunity to do a chat show, however, did come – in a most unexpected way. First, Donald Baverstock decided to drop What's My Line? without warning or consultation. Till then, I had been sailing along happily with the BBC. I had got to know their ways and their prejudices; I knew most of their unspoken rules, and I liked most of the people I worked with, from stage staff to directors. The atmosphere was good, possibly too comfortable: a creeping, but happy paralysis that seems to affect all organisations where the dreaded profit motive doesn't seem to apply; where no one worries about pencils or paperclips or trips to far-away places that take three weeks, not three days.

Baverstock wasn't even aware that Teddy Sommerfield had put a clause in my contract, calling for consultation or compensatory payment in default. Baverstock probably would not have cared anyway. And it was cold comfort to me, since I have always put programmes way ahead of the rewards that go with them. This is not some piece of pious artistic junk; it is just a matter of common sense. If you're going to survive, the viewer doesn't care what you are paid, but what you do. Somewhat like a friend of mine who always tries to restrain me on the racecourse by pointing out that it really is better to have a winner at two-to-one on, than a loser at a hundred-to-one. Anyhow, Baverstock's ploy made me uneasy. There were lots of changes happening at the top in the BBC and, at last, they were becoming aware of the competition threatened by the hungry boys at ITV.

The 1964 summer break was coming up when I was asked to go to Television Centre to discuss the future with Baverstock, the steely-eyed Michael Peacock and Stewart Hood, the droll Scot I had known from his days as news editor at Broadcasting House. I had a feeling I wasn't going to enjoy the meeting and I was right. After the usual shadow-boxing, they came to the point; they thought it was time to rest This Is Your Life. I was very annoyed and felt the only reason I was being told at all was because I had kicked up a fuss about the other programme [Bigredbook.info editor: The other programme being What's My Line?].

For the first time, I began to have serious thoughts about leaving the Corporation. What a comfort we now had ITV. However, I chided myself, silently, not to be hasty and to remember how much I enjoyed the whole ambience of the BBC, and how it had become so much part of my world, even if I had not proportionately become a part of its.

Perhaps they would have something interesting to offer. I waited. I liked Stewart Hood immensely; he was an off-beat character, but, I felt, thoughtful, sincere. Bouncing Baverstock I enjoyed hugely, but felt no warmth from him; one sensed an ego as big and bleak as a Welsh mountain. Michael Peacock I never did understand; a man of recognised talent, he was distant, suspicious and somehow patronising.

Baverstock switched on the charm. Of course, they would give me a new contract. Of course, I would be guaranteed some presumably enormous – by BBC standards – sum of money. And, of course, they would think up wonderful programmes for me.

I told them I had two wonderful programmes, both of which were now being cancelled; and that I was interested only in the programme they had to offer, not in the money. They probably did not believe me about the money, but I never did or did not do a programme because of the price tag attached to it. I always said I would like to do this or that, then let my agent worry about the money.

'We have lots of ideas that would take you around the country and give you some fun as well,' Baverstock said. He had one idea, for instance, of taking a huge auditorium in Cardiff and have Huw Weldon one side of the stage and me the other, and rivet the audience. Ho, ho, ho. Everybody chortled, but, devoted fan as I was of Huw – later Sir Huw – I couldn't for the life of me see what we could do together.

There was nothing more practical suggested. Clearly, the object of the exercise was (a) to say they were not going to do This is Your Life; and (b) to offer me a three or five year contract. I repeated that programmes were all that mattered to me and that I would think it all over.

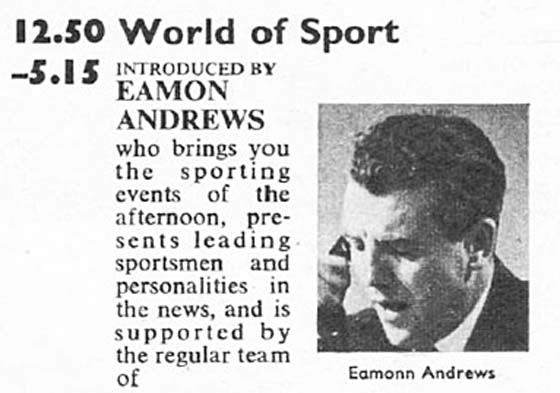

Eamonn Andrews became the original host of ITV's World of Sport in 1964

At this time, one of the BBC's executive stars, Brian Tesler, had been lured to ABC Television, the weekend contractors, as Programme Controller, and Teddy Sommerfield had gently been sounding him out about the possibilities, should I ever consider leaving the BBC. Brian, an old pal of mine, expressed a very heartening interest, because the then ITA considered ITV's weekend sport a disgrace and he was under pressure to do something to improve it. He told Teddy he was planning a Saturday show to be called World of Sport, but needed a presenter of stature, authority and appeal to give it any chance of success. Who better than Eamonn Andrews? he said. I was flattered, particularly when Brian threw in the bait of my own live weekly chat show, and I left that meeting with the BBC bosses in a daze, knowing deep down that I would not be going back.

The negotiations for my defection were carried out like some Le Carre spy plot. To ensure absolute secrecy, Brian would arrange to meet Teddy and me in a leafy London square and talk through the financial details in the back of a huge black Mercedes with tinted windows. When I shook off the nostalgia and annoyance and the fear of the freelance, I recognised Tesler's offer for what it was: a very exciting and challenging moment in my career. And, in the summer of 1964, I was being photographed with Brian and ABC's managing director, Howard Thomas, having signed a three year contract.

How This Is Your Life – or the 'Life' as the team called it – survived in Britain to be the institution it was always remained a mystery. Small boys would shout the title at me across the street. Waiters murmured it as they pushed menus under my nose. Total strangers took dares for rushing up to me in pubs, airports, theatres, with anything from a red telephone book to a red handbag, and stumble out the magic words.

Often, people wanted to know where I had the book hidden. And, just as frequently, well-known people, in the most unlikely situations, glanced over their shoulders, a trifle nervously. Once, I was in an ante-room in the Grosvenor Hotel, waiting to interview the actors and actresses in line for the London Evening Standard Awards for the Thames current affairs programme, Today. I was standing by myself, my hands behind my back, in one of which I held my radio microphone. To my pleasure and surprise, Sir Lew Grade strolled over and started chatting to me. As we spoke, I brought my hands in front of me and Lew spotted the microphone. He took a couple of steps backwards, seemed to pirouette on one toe, and glide back into the group he had just left. No wonder he had been World Champion Charleston Dancer! Anyone watching must have thought I'd eaten a lorry-load of garlic, but I knew the real reason for Lew's vanishing act.

The 'Life' gave me some of the most wonderful, touching and exhilarating moments I ever had on television. It made life-long friends for myself and the team because, when the show is taken in the spirit it is meant, it is a unique and touching experience for the recipient...

For the most part, the press gave the programme a helluva time at the beginning. Only one – dear old Peter Black of the Daily Mail – had the grace to admit, years later, that he might have gone too far. Critics come and go and new ones, from time to time, sharpen their teeth on the 'Life'. They attack its sentimentality, its alleged predictability, my own ambling idiosyncracies. And, of course, the really intellectual ones pounce on the discovery that it is only subjects of praise who were promoted, ignoring the fact that the programme is a tribute, a salute, a happy party surprise, a nod of gratitude from a community well-served...

One can imagine these critical characters organising a wedding feast and announcing that the bride's mother is in gaol, and that the groom will have a lot of catching up to do on his father who's been married ten times!

Eamonn Andrews presented 735 editions of This Is Your Life between 1955 and 1987

From the very start, the programme was handled with the gentlest care. Our researchers are as delicate as surgeons, as caring as mothers. The guest of honour was always first, the viewer second. If the guest fails to enjoy himself, the team, too, has failed. It does not follow that because a guest has a wonderful time the viewers are bound to feel the same, but we always felt we were more than half-way there. I lost count of the times I heard a guest tell the audience at the end of the show: 'I didn't think it could happen to me... I never knew a thing about it.' Even the most cynical of critics must realise now that the programme really is secret. I always regarded this as one of the essential items to the guest's enjoyment, not only because a surprise package is something everyone loves, but because, for instance, it removes any possible accusation of ego and any responsibility for the choice of guests! Apart from the programmes we have cancelled, has anyone known beforehand? Someone somewhere must have had a tip-off, but I certainly never knew of such a situation. All very well, many people said – but how did you guarantee the secret was kept? Simple. First of all, we did not make any major move until we had the permission and blessing of the nearest and dearest, the closest and strongest: wife, husband, mother, daughter, son, partner. It was never difficult to explain that the subject would enjoy the night all the more if it was a surprise. And we made no bones about saying that we would cancel the programme if the secret was blown – though it would break our hearts to do so...

As the research moved outwards, each person was warned that if they told anyone, all that they had succeeded in doing was depriving their friends of a wonderful evening, and how would they feel about that? We did not have to cancel many programmes, but one, just before the 1986 season, was a shocking blow and we were almost in tears over it...

[Bigredbook.info editor: Sadly, Eamonn never completed this section. But I can reveal that the subject was boxer Barry McGuigan, who was eventually surprised in 1988.]