Big Red Book

Celebrating television's This Is Your Life

17 December 1994

a career review

his 1980 This Is Your Life appearance

the programme's icon

the producers who steered the programme's success

This Is Your Life goes back to its birthplace

Press coverage on the return to the BBC

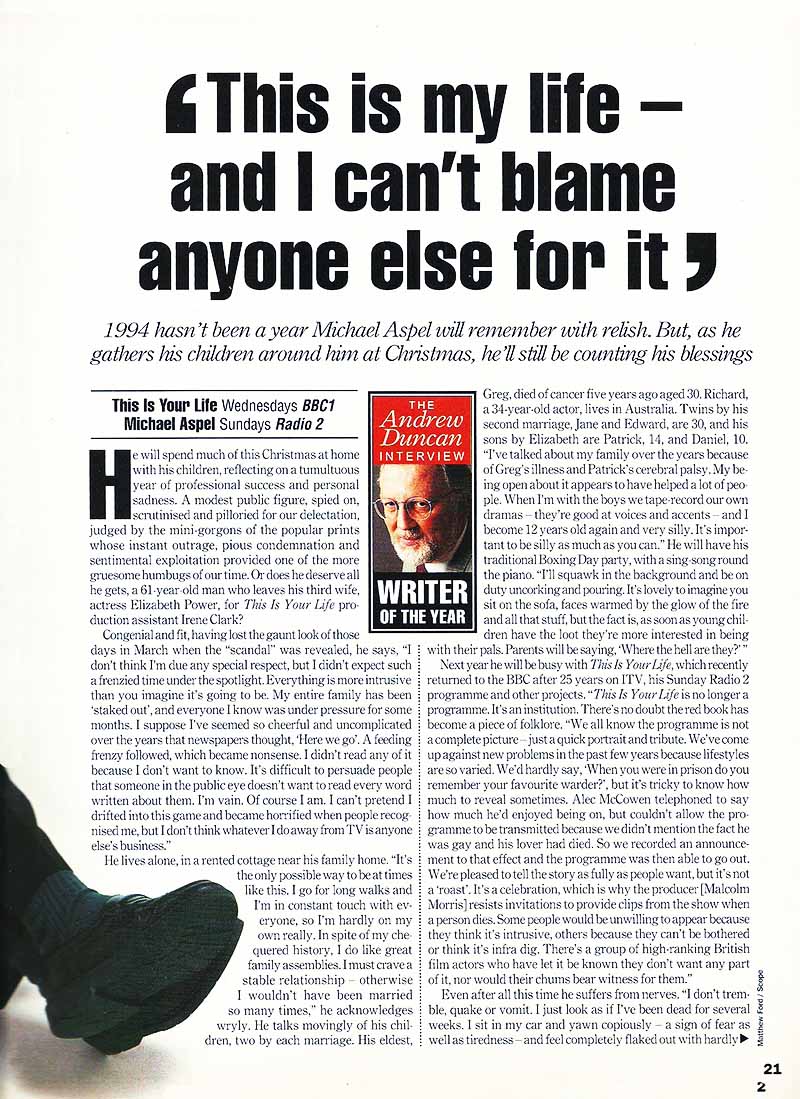

1994 hasn't been a year Michael Aspel will remember with relish. But, as he gathers his children around him at Christmas, he'll still be counting his blessings.

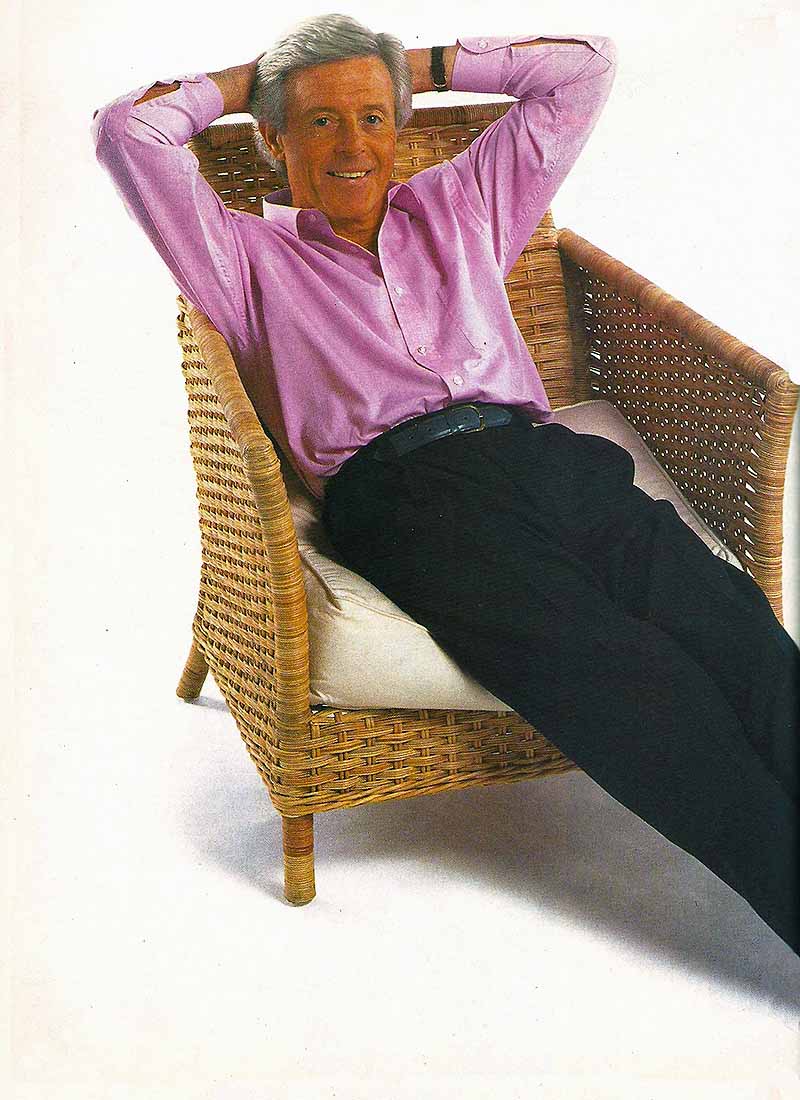

He will spend much of this Christmas at home with his children, reflecting on a tumultuous year of professional success and personal sadness. A modest public figure, spied on, scrutinised and pilloried for our delectation, judged by the mini-gorgons of the popular prints whose instant outrage, pious condemnation and sentimental exploitation provided one of the more gruesome humbugs of our time. Or does he deserve all he gets, a 61-year-old man who leaves his third wife, actress Elizabeth Power, for This Is Your Life production assistant Irene Clark.

Congenial and fit, having lost the gaunt look of those days in March when the "scandal" was revealed, he says, "I don't think I'm due any special respect, but I didn't expect such a frenzied time under the spotlight. Everything is more intrusive than you imagine it's going to be. My entire family has been 'staked out', and everyone I know was under pressure for some months. I suppose I've seemed so cheerful and uncomplicated over the years that newspapers thought, 'Here we go'. A feeding frenzy followed, which became nonsense. I didn't read any of it because I don't want to know. It's difficult to persuade people that someone in the public eye doesn't want to read every word written about them. I'm vain. Of course I am. I can't pretend I drifted into this game and became horrified when people recognised me, but I don't think whatever I do away from TV is anyone else's business."

He lives alone, in a rented cottage near his family home. "It's the only possible way to beat times like this. I go for long walks and I'm in constant touch with everyone, so I'm hardly on my own really. In spite of my chequered history, I do like great family assemblies. I must crave a stable relationship – otherwise I wouldn't have been married so many times," he acknowledges wryly. He talks movingly of his children, two by each marriage. His eldest, Greg, died of cancer five years ago aged 30. Richard, a 34-year-old actor, lives in Australia. Twins by his second marriage, Jane and Edward, are 30, and his sons by Elizabeth Power are Patrick, 14, and Daniel, 10. "I've talked about my family over the years because of Greg's illness and Patrick's cerebral palsy. My being open about it appears to have helped a lot of people. When I'm with the boys we tape-record our own dramas – they're good at voices and accents – and I become 12 years old again and very silly. It's important to be silly as much as you can." He will have his traditional Boxing Day party, with a sing-song round the piano. "I'll squawk in the background and be on duty uncorking and pouring. It's lovely to imagine you sit on the sofa, faces warmed by the glow of the fire and all that stuff, but the fact is, as soon as young children have the loot they're more interested in being with their pals. Parents will be saying, 'Where the hell are they?'"

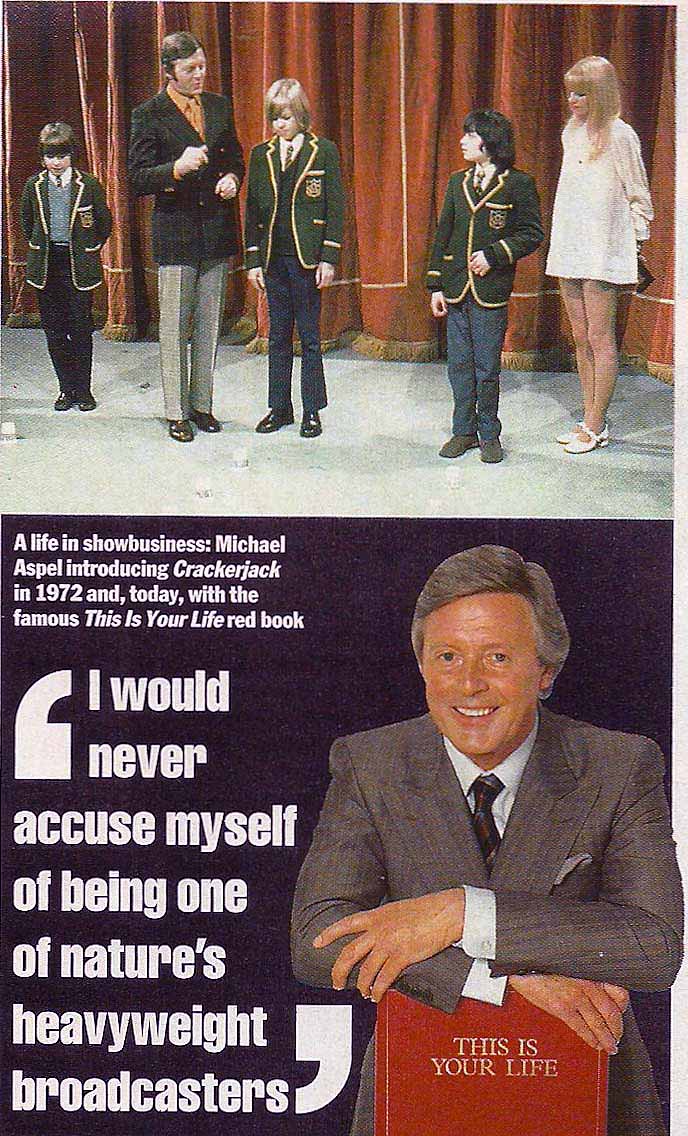

Next year he will be busy with This Is Your Life, which recently returned to the BBC after 25 years on ITV, his Sunday Radio 2 programme and other projects. "This Is Your Life is no longer a programme. It's an institution. There's no doubt the red book has become a piece of folklore. We all know the programme is not a complete picture – just a quick portrait and tribute. We've come up against new problems in the past few years because lifestyles are so varied. We'd hardly say, 'When you were in prison do you remember your favourite warder?', but it's tricky to know how much to reveal sometimes. Alec McCowen telephoned to say how much he'd enjoyed being on, but couldn't allow the programme to be transmitted because we didn't mention the fact he was gay and his lover had died. So we recorded an announcement to that effect and the programme was then able to go out. We're pleased to tell the story as fully as people want, but it's not a 'roast'. It's a celebration, which is why the producer [Malcolm Morris] resists invitations to provide clips from the show when a person dies. Some people would be unwilling to appear because they think it's intrusive, others because they can't be bothered or think it's infra dig. There's a group of high-ranking British film actors who have let it be known they don't want any part of it, nor would their chums bear witness for them."

Even after all this time he suffers from nerves. "I don't tremble, quake or vomit. I just look as if I've been dead for several weeks. I sit in my car and yawn copiously – a sign of fear as well as tiredness – and feel completely flaked out with hardly enough energy to put on the microphone. I've got close to thinking I'm entering a catatonic state, but then, thank God, the adrenaline pumps." But radio still seems to be his first love. "I was thinking this morning of my interviews on Capital [the London radio station] – 40 minutes with an international star, interspersed with records and commercial breaks, and I did my own homework. On the TV chat show [which he did for ten years] I'd be handed questions by highly educated, well-paid girl researchers. One suggested my first question to an American star should be, 'You're still an attractive man, aren't you?' I pointed out that she was 20 and a girl, and I wasn't. I once had a producer who would shout, 'Don't forget the one-liners.' Well, they either come or they don't. The greatest enemy of humour is fear, and sometimes there was a lack of rapport with guests who didn't know who the hell I was."

"You must remember I carry all the impedimenta of broadcasting in its more formal days. It's my instinct to be polite, respectful, and grab the joke when you can. American stars tend to take themselves rather seriously. Richard Gere threatened legal action if we tried to transmit a programme with references to him being a sex symbol. It seems to be getting worse, so I'm glad I'm out of it. Interviewing is an unnatural relationship and can become irksome. You meet someone you admire and in your little romantic heart you think, 'Perhaps he'll be my friend'. It seldom comes to that."

Nevertheless, his alleged income probably compensated, although he says it isn't as much as has been reported. "I'm not going to apologise for making a good living. I will be working until the day I die. Men who planned life sensibly – one marriage and grown-up children – could take months off at my age. Of all the things I've been accused of, complacency isn't one. I'm by no means secure or satisfied. I was born with a fully developed sense of guilt – all the old defensive showbiz things about money and not being worthwhile. I've not done much of the slightest importance apart from reading the news."

Self-deprecation runs through his talk, giving a "little boy lost" vulnerability said to be attractive to certain types of women. He says he never intended to be a newsreader – "I went in to help over Christmas and suddenly eight years had passed" – but there is clearly a hard core of ambition, inspired perhaps by his father.

"I was never close to him. He was an army sergeant and not home most of the time. He thought only basic jobs were for the likes of us and if you were 'artistic' you were, in his words, a poof. I only began to understand him towards the end of his life, which is something I feel quite sad about. He never gave himself, or us, the chance to get past this fairly tough relationship. Now I see myself becoming like him, particularly physically, and it's quite a shock. Although you look in the shaving mirror every day you always give a charming smile. But to catch yourself with your mouth open and your face sinking…ouch! Inside, I'm still the age I decided to be for ever more – 41. That was a very good year."

He is chirpy enough today, but admits his first instinct is not to be happy. "There's a melancholy. My mother [aged 87] is always being told, 'Cheer up. It may never happen.' Which is a silly thing to say because, so far as anyone knows, 'it' may already have happened. She worries about me in the way mums do, but she's not a natural worrier. I'm an Eeyore, who prefers to assume the worst will happen because that way life is full of pleasant surprises. I was evacuated for more than four years in the war, to Somerset, a solo kid living with older people. That might have made me want to look in the other direction whenever I see cheerful things gathering around me. I don't think people at work would regard me as a 'downer'."

It may be, I suggest, "psychology" swirling in the brain, that he is incapable of forming a proper relationship. "That sounds terribly weak and shallow, and if I admit it you might say, 'Show a bit of gumption, lad.' But it may explain things, I've lived on my own for great stretches of my life in between marriages and it got to the point where I didn't want people around me, apart from in a restaurant. There is no hint of celibacy, but I didn't let anyone spend the hours of darkness with me. I don't know why. I suffer from claustrophobia, I think."

Next year he may also do another series of Strange but True (ITV) in which he introduces stories of the paranormal. "I knew it would be well watched, but I was astonished at quite how respectful some of the snottier papers were. I thought they'd dismiss it out of hand, but we all have a little interest in the subject so they played it straight. I've had one experience myself – a girl I met filming who I dreamed of in colour, in a bright blue dress, and a week later her mother told me she'd died that night, wearing her favourite blue nightie. I'm ready to think there's nothing to it – in fact, I recently abandoned my belief in Father Christmas – but I'm sure there are areas of our minds we haven't exercised. I tried to remain detached." He accomplishes "detachment" so well that he is frequently described as bland. He shrugs. "It's a useful thing to be. If I wasn't so bland I probably wouldn't be so busy. As an actor I'd be Sam Waterston, a perpetual commentator and observer who always stands on the sidelines and never gets the girl. On form and given the right event I can shine, but I'd never accuse myself of being one of nature's heavyweight broadcasters. When I was young I thought I was God's gift to pretty well everything. But the older you get, the more you realise the real arrogance of youth is thinking you can ever crack it. What a silly boy I was."

Although he's "cracked it" more than most, there's a niggling feeling that TV isn't a job for a grown man. "It's certainly nothing I intended to do. I'd have been an adequate jobbing actor, I think. I was a very good singer as a kid, and the high point of my career was in the school opera – I've never done anything better – when I was the Firebird who transformed into the Snow Maiden, or the other way round. Then my voice broke and never returned. When I think of all the things I've pretended to want to do, singing would have been the most satisfying."

He has suffered many personal misfortunes – another son died at three days old – and I wonder if he thought fate was against him. "It sometimes seems that way, but when you start counting up, there's an awful lot of good stuff. I'm terribly lucky to be so close to my children. I know I'll grow old, but I don't think I'll ever grow up. I'll always have work, which is a very good thing. Keep the brain ticking and you're in business. I have been extremely lucky in personal relationships and have no complaints whatsoever. I can't blame anyone else for my life."