Big Red Book

Celebrating television's This Is Your Life

Elizabeth TWISTINGTON HIGGINS (1923-1990)

- The first subject to be surprised on their birthday - and to be told of the surprise in advance

THIS IS YOUR LIFE - Elizabeth Twistington Higgins, ballet teacher and artist, was surprised by Eamonn Andrews on her birthday at the Middlesex Hospital in London, having been led to believe she was taking part in a different television programme.

Elizabeth trained with the Sadlers Wells Ballet School and the Cone School, which became the Arts Educational School, where she later worked as a teacher. She made her West End debut in 1946, with the corps de ballet in the musical Song of Norway at the Palace Theatre, before appearing in Ivor Novello's musical King's Rhapsody at the same theatre.

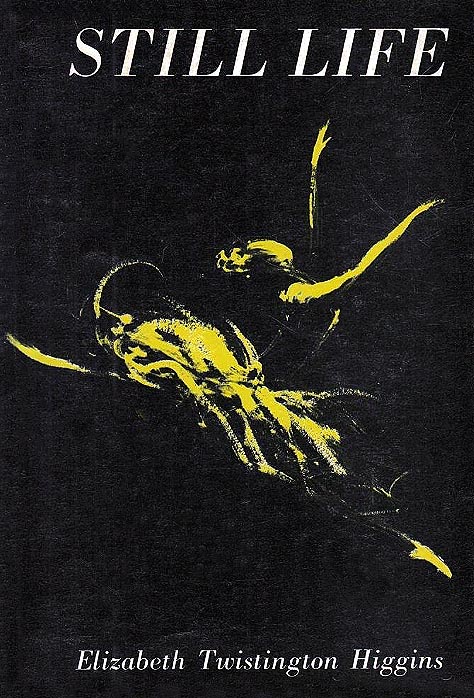

At the height of her career as a classical ballet dancer and teacher, she was struck down by paralytic polio in 1953. Despite being almost totally paralysed from the neck down, using a wheelchair by day and sleeping in an iron lung by night, Elizabeth continued to teach and, in addition, retrained as a painter, using her mouth to create still life and ballet scenes that she exhibited internationally.

Elizabeth became the first subject of This Is Your Life to be told of the surprise in advance - following doctors' advice that a sudden shock may harm her health.

programme details...

- Edition No: 169

- Subject No: 170

- Broadcast live: Mon 6 Nov 1961

- Broadcast time: 7.55-8.30pm

- Venue: BBC Television Theatre

- Series: 7

- Edition: 6

on the guest list...

- Jean Young

- Pat Dainton

- Janet Hamilton-Smith

- John Hargreaves

- Pauline Grant

- Charles Reardon

- George Bernard

- Bert Bernard

- Georgina Eskdale

- Adrian Spratt

- Jennifer Ripley

- Rosemary Howard

- Gloria Letheren

- John Ripley

- Leslie Wilson

- David Blair

- Beryl Grey

- Thomas - father

- Jessie - mother

- Phillipa Crews

- Margaret Crews Filmed tribute:

- Claire Bloom

production team...

- Researcher: Nickola Sterne

- Writer: Nickola Sterne

- Director: Yvonne Littlewood

- Producer: T Leslie Jackson

- names above in bold indicate subjects of This Is Your Life

from ballet to ballroom

the show's fifty year history

Elizabeth Twistington Higgins: This Is Your Life

A profile of the ballet dancer

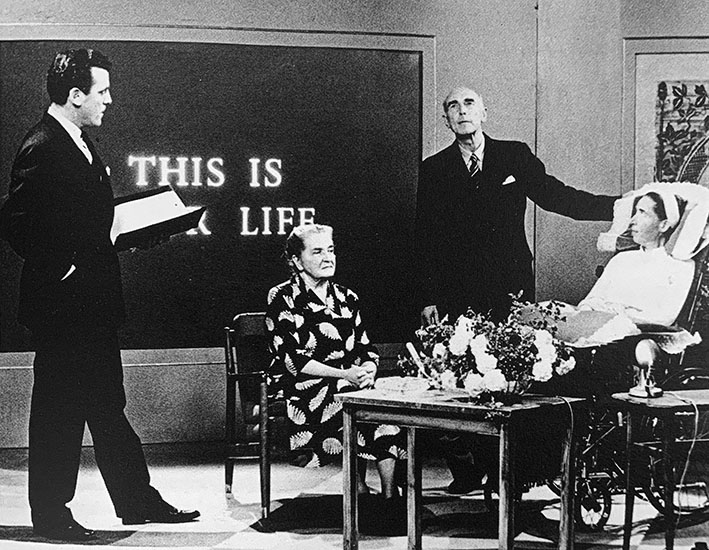

Photographs of Elizabeth Twistington Higgins This Is Your Life

My birthday in 1961 is firmly etched in my memory. I was asked by the BBC to appear in 'Town and Around', a daily magazine programme about the South East of England. When they suggested that I went to London for the interview, I was a bit suspicious. In normal circumstances, a mobile camera team would have come to Dover. My suspicions were well-founded; this was only a ruse to get me to appear on the weekly programme This Is Your Life, which gave a glimpse into the lives of celebrated or interesting people. I was amazed that they should consider me a suitable subject.

An appearance on This Is Your Life was supposed to come as a complete surprise, but my doctor had advised the producer not to spring a sudden shock on me. I was shocked. I burst into tears. I felt I could not face my friends and relations saying kind and flattering things about me for half an hour. Overwhelming kindness always upset me.

I told Matron I could not do it. She seemed very disappointed but I think she understood. I was glad she was the only person who witnessed my emotional outburst. She left, saying that the decision was entirely up to me; I was to think it over and let her know in the morning.

This bombshell interrupted a painting lesson with Rosemary and had completely shattered my powers of concentration. There was no more work that afternoon.

I discovered that Rosemary was already in on the secret, and she spent the rest of the afternoon calming me down. She told me that, of the four lives prepared for the following week, three had left the country. If I did not appear, the programme would either have to be cancelled or a repeat performance shown. She was very persuasive. I felt I could not let everyone down and accepted the challenge, though reluctantly. I had accepted challenges before, but this one scared me stiff. In the theatre, I would have given my bottom dollar for this kind of publicity. Now I was in a wheelchair, I did not want to appear before an audience.

The nurses knew that something was troubling me but, as I was under a vow of silence, it was impossible for me to communicate with them. I could not eat or sleep or concentrate; my thoughts were focused entirely on the ordeal ahead. My mind was so preoccupied that I never even thought of buying anything special to wear on this great occasion. Looking back, I am still amazed at myself – it was so unlike me. I felt sick with anxiety and nerves and the next four days seemed endless.

On the fifth of November, I was formally admitted to the Observation Ward of the Middlesex Hospital in London. Here too, secrecy prevailed and I was obviously a rather mysterious patient. I was under the care of the RMO, and his young Houseman thought I was an interesting case. After asking me a lot of questions about my illness, he looked incredulously at me and said, 'You're a living miracle!'

This was his first meeting with someone who had had respiratory polio.

Early the next morning, the BBC took possession of my room. Everything was moved out of the way; cameras brought in, cables laid, lights fixed, sound tested; the interviewer, Nancy Wise, came in and we were on the air.

The conversation that followed was spontaneous and went off quite well, apart from one rather awkward moment.

'Do you miss the world of ballet?'

For a second I was completely taken aback by such an obvious query, and sharply retorted,

'Of course I do!'

This was not very polite of me and Nancy must have felt terrible having asked such a tactless question. I have always been a volatile and emotional person. If only I could react more slowly and had greater control over my emotions, I would so often save others from being hurt and embarrassed.

At the end of the interview, Nancy said to me, 'As it is your birthday Elizabeth, the BBC has prepared a surprise for you.'

She turned to face the door and in walked Eamonn Andrews.

After a few words of greeting, he asked me if I would come to the Television Theatre that evening and see what other surprises the BBC had in store for me.

I spent the afternoon resting in my respirator. I was being washed and dressed for the evening performance when our pre-recorded interview was shown in 'Town and Around'. I did not see myself, nor did I hear Eamonn Andrews say that, for the first time they were breaking the usual rule of silence for the evening's performance of This Is Your Life. Owing to my disabilities, it had been decided to warn me beforehand that I would be appearing.

The RMO came in to see that I was feeling all right before I set off in the ambulance for the theatre. We got there with five minutes to spare. Fortunately, I did not know we were cutting it as fine as this, or I would have been in a terrible state.

I was backed down a ramp directly on to stage level. There, one of my dancing partners from Song of Norway greeted me and gave me a birthday present – the first and only one that day. I only appreciated the thoughtfulness of this gesture when everything was over.

The atmosphere in the theatre was tense. I was acutely aware that everyone was willing me to give my best. Everywhere I looked, there were stage hands at the ready; I saw oxygen in the wings in case of emergency, but no guests.

I was pushed into position on the stage behind a table bearing microphones, a bowl of pink carnations and a whirring fan. The make-up girl stepped forward and powdered my face. My white pillow slips were changed for blue ones. As the programme was timed to the final second, Eamonn said he would prefer me to keep quiet! He was still talking to me as the signature tune started. I was quite unaware that there had been any warning – Eamonn disappeared through the curtains and we were on!

I heard him say, 'Tonight, This Is Your Life is a birthday party, with birthday surprises for one of the most remarkable and courageous ladies I have ever met.'

The curtains parted and I found myself facing a theatre full of people. I was back on stage!

As the applause died away, I heard the music of Les Sylphides and, on a monitor set, I saw some children dancing the Nocturne from this lovely ballet. They were pupils from the Cone School and were the first of my guests.

The others followed in quick succession: Jean Young, an Associate Member of the Royal Academy, recalled her memories of my dancing; Pat Dainton, one of my most talented and industrious pupils, remembered me as her teacher, as did Claire Bloom in a tele-recorded message from Hollywood.

The music of Song of Norway heralded the entrance of singers Janet Hamilton-Smith and John Hargreaves, followed by Pauline Grant, the choreographer for whom I worked so often; Charles Reardon, the stage doorkeeper, reviving happy memories of the time I spent at the Palace Theatre; the sound of squabbling off-stage, and the rushed entries of the Bernard Brothers dressed as Cinderella's ugly sisters – memories of the pantomime at the London Palladium.

Following my theatre colleagues, two children I used to teach at Coram's Fields. Then on to the present. Jenny and John Ripley; Rosemary Howard and one of her pupils who had modelled for me; Leslie Wilson, representing the Medici Galleries: David Blair and Beryl Grey from the Royal Ballet; my mother and father and finally, Margaret Roseby, also from the Royal Ballet, and her daughter. Eamonn presented me with the script and the curtain fell. The half hour had passed swiftly and pleasantly and I had enjoyed it after all.

This was the last I saw of Eamonn as he had to fly to Ireland immediately after the show. I felt slightly disappointed that he was unable to be with us, but suddenly, my sister Brighid and her husband were on the stage beside me. Unknown to me, they had been in the audience. They too were invited to the party held specially for all who had taken part in the programme. Here I met the production crew and was at last able to chat with my guests.

By eleven o'clock I was absolutely whacked. My thanks to everyone were completely inadequate – I was far too tired and breathless.

The RMO greeted me on my return. He told me he had watched the programme with interest and with a degree of clinical concern. He could tell by the rapid movement of my neck muscles that I was exceedingly nervous, and that it took a good ten minutes for my respiration rate to return to normal.

The Houseman offered to help the nurses put me to bed. In spite of my exhaustion, his thoughtfulness amused and delighted me and I was quite disappointed when they said they could manage without him!

It was well after midnight before I was settled in my cuirass, but I was far too keyed up to sleep. The past few days had been such an emotional strain that it was to take nearly a week for me to unwind. Thoughts raced through my brain, and sleep, which is always elusive, escaped me altogether.

I returned to Dover Isolation Hospital two days later. Travelling in a hearse-like Daimler ambulance, I felt I was very much on view. All along the route, people recognised me; they stood up in the buses and along the streets, waving as I passed. I was staggered to think that my brief appearance on television had brought this publicity. The nurse beside me acknowledged these friendly greetings. She became quite tired waving continuously on my behalf, and said she wouldn't be the Queen for anything!

Gradually, I learned a little more about the preparations for the programme. I had not been the only one who had suffered agonies of nerves. My guests had been rehearsed for two days and had had to learn a script. Some of them were professionals and no doubt took it in their stride, but the others were unused to appearing in public and found it a terrible ordeal. Most of them were seeing me disabled for the first time and must have been shocked by what had happened to me. This must have added to their strain and I knew how I would have felt in their place. I think they were very plucky to appear in the show.

The most trying moment for me had been the appearance of my parents. I very nearly broke down. My heart ached with sympathy for them; I knew what it was costing them to stand up in public and make their speeches. By nature, they were reserved and retiring and, considering we had faced a live audience in the theatre as well as approximately fifteen million viewers, it was no wonder my poor mother got het up during rehearsals and felt she would never learn her lines. At one stage she even forgot which of her children she was talking about.

The producer, Leslie Jackson, a sensitive, very persuasive Irishman with several years' practice at overcoming people's diffidence and immediate reaction to a public appearance, must have had an awful time with my family. Whichever member he phoned, they all gave him the same answer, 'Good gracious! You'll never get them to do that!'

I learnt later that my father told him he would walk round the garden until the show was over!

There must be a story behind the life of every disabled person. That mine was chosen to be shown on television was for its visual appeal, and because it was easy for people to realise the enormous change from dancing on stage to a life of immobility in a wheelchair. There was no doubt at all that the public's imagination had been captured. Not only those leading a normal life, but disabled people too, known and unknown, wrote to me. The programme, they said, had been inspiring and encouraged them to new efforts. I was surprised and felt very humble. It had never occurred to me that my struggles to paint could have helped others in this way. It was one of the unexpected rewards. The other came a few weeks later. A special despatch rider drove up to the hospital with an enormous red morocco-bound book of photographs – a wonderful souvenir of an unusual and very happy birthday.

'Would you like to go to London for the weekend?' asked Marion in a strangely casual voice.

Propped up in a wheelchair in her 'studio' cubicle at the Dover Isolation Hospital, Elizabeth felt a pang of apprehension. Since she had become paralysed she seemed to have developed telepathic powers.

Sometimes she would dream about somebody she had not thought of for years and the next day he or she would walk in on a surprise visit; often she knew exactly what she was going to be told before the person concerned had even opened his mouth.

'Why this weekend?' she asked.

'Oh well, the BBC... would like to interview... for Town and Around...'

'Not This Is Your Life?' Elizabeth asked with a flash of intuition. 'Oh no. I could never... No, no.'

The very idea of appearing on television provoked Elizabeth into an emotional outburst and her eyes filled with tears. Matron seemed understanding but disappointed at this unexpected reaction and leaving the room she said. 'Well, my dear, the decision is entirely up to you. Think it over and let me know what you decide in the morning.'

Rosemary Howard sighed. She knew that the rest of the afternoon was ruined as far as painting was concerned. She, too, had been in the know over the hush-hush BBC programme, and now she shared some of Matron's surprise at Elizabeth's reaction.

'I could not face my friends and relations saying kind and flattering things about me for half an hour,' explained Elizabeth. 'You know how kindness upsets me.'

'But I thought you stage people had a motto about the show always going on,' said Rosemary in calm and reasonable tones. 'Why, as a dancer you would have given anything to be on such a popular programme, to be seen by millions...'

And that was the subconscious obstacle. Elizabeth was no longer a dancer. In her last public performance at the London Coliseum, she had been lithesome and lovely in a gorgeous costume. How could she appear in a wheelchair after that? But Rosemary continued to appeal to her 'trouper' instinct by telling her that of three 'lives' prepared for the programme, two had left the country which only left her.

'If you don't appear they'll have to cancel the show,' she concluded with a telling psychological thrust.

The last thing Elizabeth could do was feel that she was letting other people down so reluctantly she decided to go through with it. Having sworn an oath of secrecy, she could not explain to the nurses what was making her so edgy.

On November 5, 1961, Elizabeth arrived at London's Middlesex Hospital and was admitted to the Observation Ward. The staff regarded her with curiosity. They seemed there was something out-of-the-ordinary about this case and their suspicions were confirmed early the following morning when a BBC team invaded her room for the recording of the Town and Around programme which was the official reason for her visit.

Television cameras glided over the highly polished floor, technicians exchanged jokes in their private language, hot lights bathed the room in brilliant light then faded as the lighting man pondered a better angle. His earphones making him oblivious so the organised confusion about him, the sound man placed microphones and checked his levels.

At last a hush fell. The producer made a sign to Nancy Wise who opened the programme. When the interview came to the end Miss Wise said, 'As it is your birthday, Elizabeth, the BBC has prepared a surprise for you.' And right on cue Eamonn Andrews appeared and asked her with all his Irish charm if she would visit the television theatre that evening to see what else the BBC had in store for her.

Normally the first a subject knows about appearing on The Is Your Life is when he suddenly finds himself in front of cameras but in this case, it had been agreed with the medical authorities to give Elizabeth fair warning. A sudden shock could make her forget to breathe and the programme would find itself with more than its usual share of real-life drama. At the beginning of the programme Eamonn would explain that in this particular instance, secrecy had been waived for medical reasons.

When the cameras and their snaking cables had been wheeled away Elizabeth was put into her respirator so she could rest during the afternoon. As dusk fell over wintery London nurses began preparing her for her ordeal and such was the rush that she missed seeing her interview on Town and Around.

The Resident Medical Officer appeared to give her a last-minute check-up before she was wheeled into a Daimler ambulance which arrived at Shepherd's Bush with only five minutes to spare. Luckily Elizabeth did not realise this because she has always had strict views on allowing plenty of time before a performance, and the seemingly casual way television shows come together at the very last moment is terrifying enough for the able-bodied let alone anyone who has to remember to take that every breath.

The ambulance reversed to a ramp and swiftly Elizabeth was wheeled on to a set where one of the boys she had danced with in Song of Norway placed a birthday gift on her lap - her first present that day. She only appreciated the thoughtfulness of the gesture when the show was over for as she was positioned by a table, on which pink carnations concealed microphones, she was only aware of the tense atmosphere around her.

'Everyone was willing me to give of my best,' she said later. Meanwhile, she noticed a cylinder of oxygen in the wings - the BBC was not taking any chances. A make-up girl dusted her face lightly with powder; someone replaced the white pillowslip with blue. Beside her Eamonn chatted casually and was still chatting when the theme music began.

Suddenly he was gone and Elizabeth heard his voice from the other side of the curtains.

'Tonight, This Is Your Life is a birthday party,' he announced, 'with birthday surprises for one of the most remarkable and courageous young ladies I have ever met.'

The curtains swung back. Elizabeth saw a blur of faces in the auditorium and with a sudden shock, realised that she was on stage again.

The applause blended into music. Of course, what else but 'Les Sylphides'. And on the monitor screens the audience saw a film recording of children dancing the Nocturne from this ballet. They were children from the Cone School where Elizabeth had once been both student and teacher, and they were the first to appear on the stage with her. After that successive periods of her life were brought into focus as Eamonn called out name after name and old friends walked into view. Jean Young, an Associate Member of the Royal Academy who had herself become a painter, talked about Elizabeth's dancing years, one of her best-ever pupils described what it was like to train under her, and so did Claire Bloom in a prerecorded film from Hollywood.

Suddenly music from Song of Norway filled the auditorium, and on came John Hargreaves and Janet Hamilton-Smith to reminisce about the show and Elizabeth's part in it. They were soon joined by the choreographer Pauline Grant for whom she had so often danced. The Palace Theatre days were rounded off by anecdotes from the stage doorkeeper Charles Reardon and memories of her panto days at the London Palladian were revived by the Bernard Brothers who appeared clowning as the Ugly Sisters.

Elizabeth had dreaded the programme, but as familiar faces appeared from her past she could have easily forgotten she was on television in the magic of those fleeting minutes, especially when she saw the children she had taught at Coram's Fields smiling at her... Grimmer memories returned as Jenny Poynting talked about the long painful nights in the early days of her paralysis and Rosemary Howard described the terrible effort it had taken for her to become a mouth painter. Then Leslie Wilson of the Medici Galleries appeared just to say how successful that effort had been.

What could have been the thoughts of Tom and Jessie Twistington Higgins when they were ushered on and saw their paralysed daughter the centre of so much tribute and love? They were a reserved couple and seeing them in the bright stage light Elizabeth felt deeply sorry for them, knowing the strain it was for them to stand up in front of a theatre full of people - and fifteen million viewers - to say their carefully rehearsed lines.

From the Royal Ballet appeared Beryl Grey - who talked enthusiastically about Elizabeth's paintings - Margaret Roseby and David Blair, then Eamonn made traditional presentation of the script, the curtain fell... and then the real party began. Elizabeth was so exhausted she found it a great strain to chat to those who had come in secret to be with her for her big moment, but when she was finally wheeled back to the ambulance she would not have been surprised if it had turned into a pumpkin. To carry the analogy further, the Fairy Godmother role had been filled by Roy Nash of The Star. Believing that Elizabeth's work should receive wider exposure, he had written about it to the BBC Monitor art programme. His letter was passed to the 'appropriate department' which turned out to be This Is Your Life.

Elizabeth was welcomed back to the Middlesex by the RMO who had watched her appearance on the screen with professional concern.

'I could tell how nervous you were at the start by the rapid movement of your neck muscles,' he said. 'It took ten minutes for your respiration rate to get back to normal.'

As a result of the programme the Dover Isolation Hospital received sackfuls of mail for Elizabeth. There were hundreds of letters to be answered and her family rallied to help her with the task. The bulk of them contained messages of goodwill or expressed thanks for the faith. I have known other handicapped people who have received similar letters and been made utterly miserable by them.

Series 7 subjects

Max Bygraves | Mario Borrelli | Alastair Pearson | Brian Rix | Derek Dooley | Elizabeth Twistington Higgins | Sandy MacPhersonRonald Menday | Harry Day | Peter Finch | Charlie Drake | Timothy Cain | Isabella Woodford | David Park | Sefton Delmer

Coco (Nicolai Poliakoff) | Jenny Gleed | Arthur Davies | Tom Evans | David James | Kenneth Horne | Marie Rambert | David Butler

Glen Moody | Kenneth Cooke | Tom Breaks | Dora Bryan | Bob Oatway | Acker Bilk | Hester Meakin | Joe Filliston | Ellaline Terriss