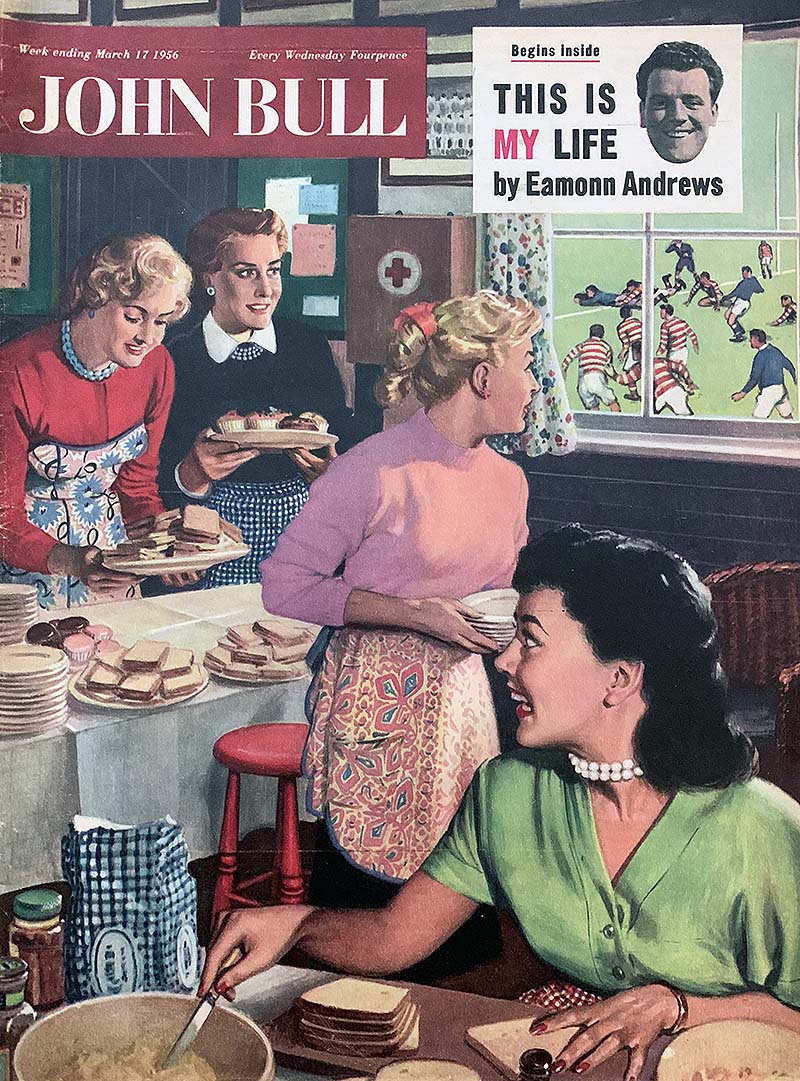

Big Red Book

Celebrating television's This Is Your Life

17 March 1956

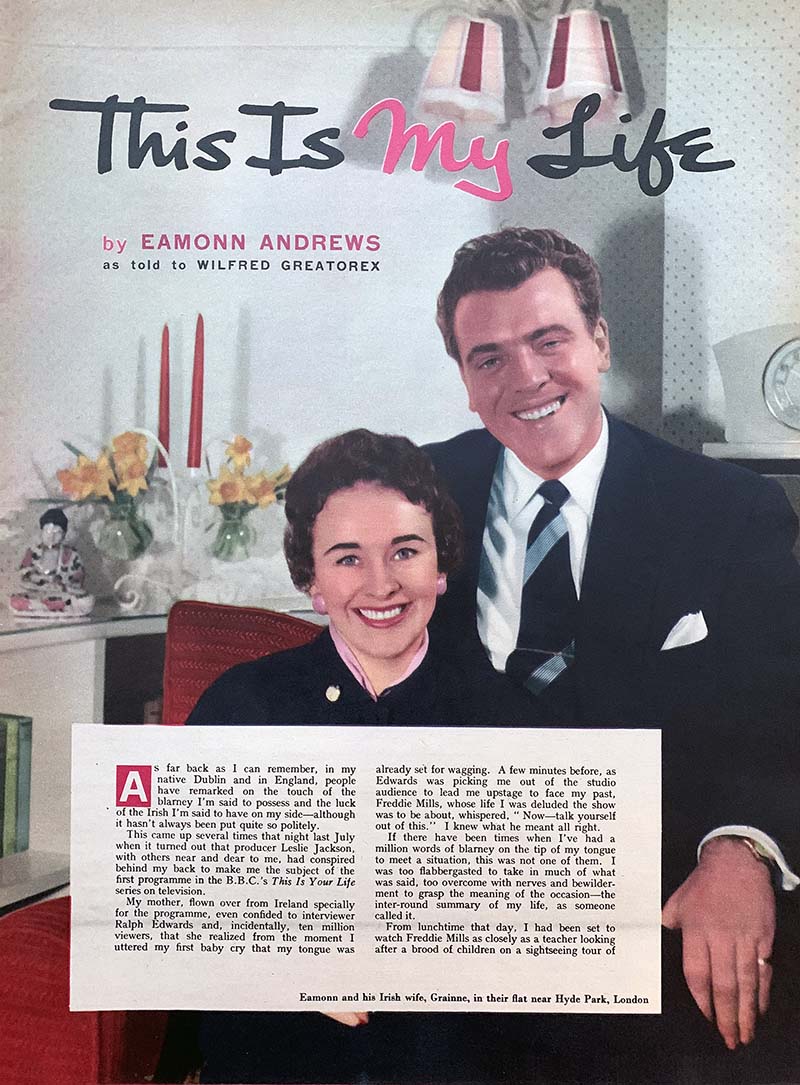

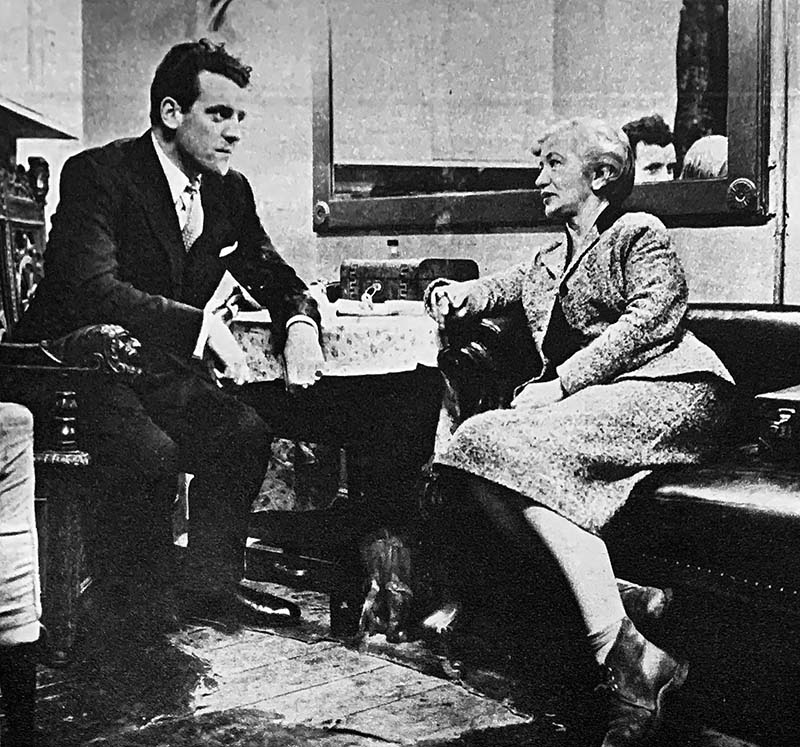

Eamonn and his Irish wife, Grainne, in their flat near Hyde Park, London

a brief biography

The Legend That Was Eamonn Andrews

a celebration to mark the presenter's centenary year

first-hand recollections

the man who created it all

the producers who steered the programme's success

Eamonn's first appearance as a subject of This Is Your Life

Eamonn Andrews has turned down many offers for his life story, and when assistant editor Wilfred Greatorex approached him on behalf of JOHN BULL recently, he at first said no. "For one thing," he explained, "a man shouldn't commit himself to autobiography until he's around the fifty mark." But Greatorex kept talking, and after three and a half hours Andrews said yes.

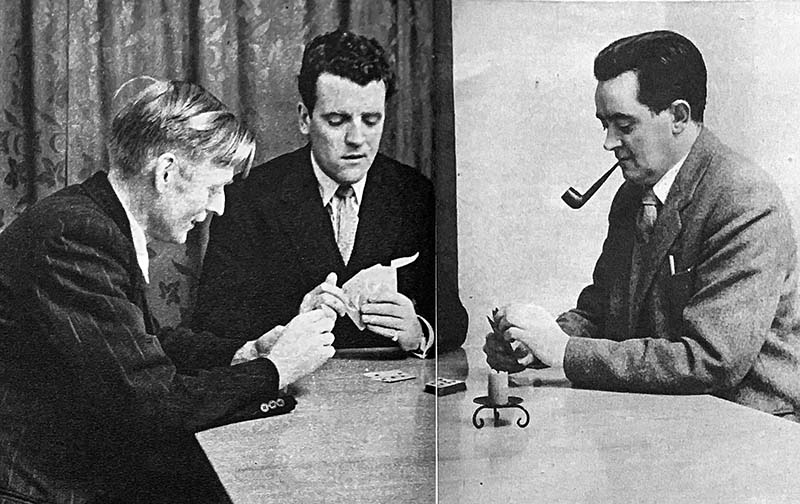

The next problem was time, for Andrews is fully booked with radio and TV work. The answer was a tape recorder. Greatorex met him at his flat near Hyde Park whenever there was an hour to spare – "mostly at a time when London isn't properly awake," says Greatorex - and with the microphone between them Andrews talked and Greatorex prodded and prompted.

When the interviews were over, Greatorex checked with the tape manufacturer and learned that Andrews had used just under three and a half miles of tape to record the first thirty-three years of This Is MY Life (page 9). Carrying the mathematics of autobiography a little farther, Greatorex worked out that if we had waited until Andrews was fifty, there would have been enough tape to stretch from Broadcasting House to Lime Grove and back.

by EAMONN ANDREWS as told to Wilfred Greatorex

As far back as I can remember, in my native Dublin and in England, people have remarked on the touch of the blarney I'm said to possess and the luck of the Irish I'm said to have on my side - although it hasn't always been put quite so politely.

This came up several times that night last July when it turned out that producer Leslie Jackson, with others near and dear to me, had conspired behind my back to make me the subject of the first programme in the BBC's This Is Your Life series on television.

My mother, flown over from Ireland specially for the programme, even confided to interviewer Ralph Edwards and, incidentally, ten million viewers, that she realised from the moment I uttered my first baby cry that my tongue was already set for wagging. A few minutes before, as Edwards was picking me out of the studio audience to lead me upstage to face my past, Freddie Mills, whose life I was deluded the show was to be about, whispered, "Now - talk yourself out of this." I knew what he meant all right.

If there have been times when I've had a million words of blarney on the tip of my tongue to meet a situation, this was not one of them. I was too flabbergasted to take in much of what was said, too overcome with nerves and bewilderment to grasp the meaning of the occasion - the inter-round summary of my life, as someone called it.

From lunchtime that day, I had been set to watch Freddie Mills as closely as a teacher looking after a brood of children on a sightseeing tour of London. To keep tags on Freddie I went everywhere - or nearly everywhere - with him. I went through the motions of taking part in a "phoney" sports panel programme with him, for which Leslie Jackson had laid on everything at Lime Grove, even to the cameras, crews, and make-up. I even took Freddie home to our flat at Lancaster Gate for dinner. He wasn't difficult, and in view of the fact that he knew, and I didn't know, that this was a "double take," this was not surprising.

I had seen Ralph Edwards doing the show in America, and knew all about the need for surprising the person whose life was to be televised. Yet once I was onstage, I could not understand how my family and closest friends could have kept it from me for so long. That was the shock of it, though I have since been able to see more rationally, as interviewer and co-perpetrator, how much This Is Your Life relies for its impact on gentle deceptions.

I wondered how Leslie Jackson had managed to keep my mother in London for a full twenty-four hours without her beating him to the punch and at least telephoning me. I wondered how my wife, Grainne, especially, had kept the whole thing quiet and beyond my suspicions. As I learned afterwards, she had her dicey moments. For some weeks, Grainne had been calling regularly at the doctor's each Friday, and not once had I been able to go round and collect her. This day would have to be different.

I left a message with our housekeeper, Alice, that I would drive Grainne home for lunch. Yet, when I arrived, she had left; and on inquiring I was told that she had gone shopping. In fact, she was rehearsing her part in my life. Later, when a friend who was also with us for dinner had a conversation with Alice in her native German, I thought he was merely showing-off after his holiday in Austria, whereas Alice was telling him to get me off the premises so that Grainne could leave for the studio without my knowing.

When Grainne did make her appearance on that stage, she asked me quietly: "Well, where's that second line of defence now?"

This is a factor in my life Grainne knows all about, one that I have always regarded as more dominant than all the so-called blarney and so-called Irish luck. All through the years, from late childhood, I've invariably sought and borne in mind a second line of defence in case the worst should happen in anything I do or try to do. Maybe it's a streak of pessimism, or realism, or escapism. When I played truant from my job as an insurance surveyor in Dublin to visit Belfast for material I needed for a broadcast the following week, I worked it out that the worst consequence would be the sack and having to line up in a dole queue.

There have been many times when the worst might have happened. Sometimes, in those early Dublin days, my mother would remind me that I was treading a tricky path. With the family, experience of years when there was unemployment all around them and other troubles, too, had left its mark. My mother and father both regarded the security of a regular job with a pension as preferable to an over-ambitious seeking after fame and fortune.

Even as a grown young man I often had this made clear to me. And that night last July when I was trapped in front of the cameras without my second line of defence, my mother, as she came up to me, whispered: "I hope we haven't done wrong in not telling you about it. I'm still not sure."

My parents' preoccupation with security and a quiet, ordered family life was understandable. When I was born, their first child, on December 19, 1922, they had just lived through the stormiest period of modern Irish history, the 1916 insurrection and the bloody years that followed - and the memory of the terrible deeds of the notorious Black and Tans was still fresh in the people's minds.

As I grew up in a developing suburb of Dublin, I was to hear a lot about this disreputable task force. Sometimes my father would recall them, but never with rancour. He was a gentle, kindly carpenter with no bitterness in his heart, and his interests were concentrated on his work, his family and amateur theatricals. He was serious-minded and would worry a lot, and I never knew his hair to be anything but grey.

In that year of my birth, the Irish Free State came into being and a leader destined for world fame named Eamon de Valera was playing his early, vital part in the building of the new republic outside the British Commonwealth. I did not know if I was named after him or, if I was, why my name has two "n's." It is possible that the "Eamonn" came from my paternal grandfather, Edward Andrews, for Eamonn is Gaelic for Edward.

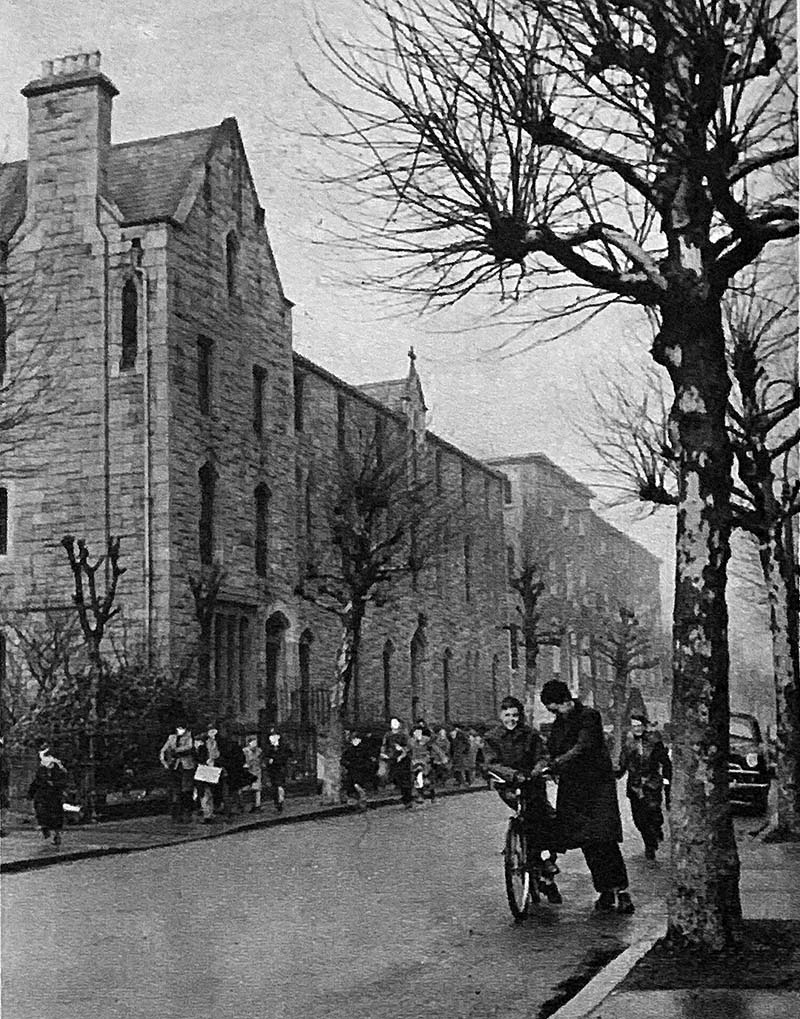

All through my childhood, Ireland faced economic troubles. For years, it was a patriotic thing to burn turf in the domestic grate. It gave off a mountainy-sweet smell that pervaded our part of a large terraced house in Synge Street, so labelled after the Irish writer John Millington Synge. In that street George Bernard Shaw was born.

When I was five, we moved a short distance away to a slightly bigger house in Donore Avenue, Fairbrother's Fields, to make room for an extension to the Christian Brothers' School in Synge Street. Our new house had three bedrooms, but my father sacrificed one to make a bathroom.

Soon after our removal, my mother took me to school for the first time. We were greeted by an impressive kindly nun who must have been six feet tall, Sister Bonaventure. In class, she would kneel with a book open on her long black habit, and it was during these lessons that I first knew that I could pick out words – three letters only, but the feeling was wonderful.

After three years, it was time for me to move on. There was a shortage of places at the Christian Brothers' School, but they fitted me in because our family had been displaced to allow their earlier extension. I was in for several shocks. I was big for my age and soft, and the boys at this school were tough. Soon, I was the butt of any boy when the fighting instinct took him. I wept and never retaliated.

What was even worse was that as a by-product of the new national independence, the drive was on for bilingual teaching – in Gaelic and English. Gaelic had never been taught at the convent school, and I felt lost in class. I became a lonely and terribly shy child. Home was the place to be, and there I read voraciously; never the set school work, but books on nature. I started a notebook and went through a long period making copious notes on the otter. I sought books on it from the school library, and others from the public library in Kevin Street, and when I found I couldn't get enough, I did an illegal thing: I joined another branch of the library.

Even with a fiction and a non-fiction ticket at each, I could not get enough books. Several times I borrowed other people's tickets and dozens of books I read in a week. I filled pages of my notebook on the otter. Once or twice, the library assistants pulled me up, but I found I could bluff my way out quite easily.

At home the family was growing. Peggy came, then Kathleen, and Noel and Tresa, and it wasn't until many years later that I wondered how we all fitted into the tiny house. Even there, I tended to prefer my own company and spent many an evening in the front parlour which was reserved for special occasions which never arose. At table, my mother would often remark that I was reading again and I would put the book down reluctantly. One day I had an answer. "It's good for the digestion," I said. "It makes me eat more slowly."

School was an increasing burden, and when we moved into the secondary level where both mathematics and Latin were done through Gaelic it was much worse. I took no interest in homework, relying instead on going to school early the following morning in the hope that somebody would give me a "cog" from his exercises. At this stage I had only one close friend at school, but he couldn't help me in this regard: when the end-of-year examination results came out I was second last and he was bottom.

Though still handicapped by my late start in Gaelic, I was fascinated by some of the folklore that the revival of the language had turned up. The tales of the Fianna, the traditional lands peopled with magic horses and giants seven feet high, appealed strongly, and there was Cu Chullainn, the great warrior of legend. I pictured the scene vividly as Cu Chullainn, in his last great battle, fought and killed so many opposing warriors that he had to tie himself to a post to keep on his feet, and even then fought so fiercely that nobody dared to go near him until the ravens landed on his shoulder and they knew that he was dead.

He was my great hero, and just for a short time I tried to emulate his drive - on the football and hurling fields. This merely gave some of the boys a better chance to knock me around legally, and they gave me a hell of a time. I drew within myself again, and my greatest enjoyment was to join my father on the motor bike he had bought. We went on great mystery tours around Dublin. I rode on the pillion with a mack over my head, and then he would stop and say: "Right! Take it off. Where are we?" I came to know the glory of Dublin Bay on a summer's morning this way, and such beauty spots as Rathfarnham and Dollymount, and once we went to Ringsend, where my father worked for the Electricity Supply Board.

One spring day, he took me to the Hellfire Club, a stone ruin topping one of the hills, and there he told me the legend behind it; something about the boys gaming and carousing up there until somebody dropped a card and, looking down, they saw that one of the players had a club foot. They all sold their souls to the Devil and the place went up in smoke. It was a good story, but it seemed to be short of something, and for weeks afterwards I wondered about it.

My father was a deeply religious man, but that didn't stop him from remarking on my softness sometimes. He seemed to know all about the beatings I was taking at school, though I never reported them to him, and he was perturbed by my shyness. In the next class to me at school - three classes used to go on simultaneously in one large room - was a boy called Sean Tallon whose fighting prowess I envied. He was small and light and so dainty on his feet and handy with his fists that even the school bullies learned to keep clear. In schoolyard fights, he was tremendous. A real fury he was, and watching him from the ringside circle of fight-mad schoolboy admirers filled me with respect and awe. I felt my own shortcomings, and it didn't help when for some strange reason I became a choirboy - at St Theresa's in Donore Avenue. It was with the choir that I did my first broadcast, and there was a lot of excitement at home because we had no wireless and my father set about building a crystal set.

After evening practices, and at other times, the choirboys displayed the usual gentility of their kind by making life as intolerable as possible for the church clerk, John Kenny. He was a young man with masses of black wavy hair, but he looked older than his years, and the regular duty imposed on him of having to chase wayward choirboys off the premises while wearing his ankle length soutane probably had something to do with this.

No sooner had he run us out of the grounds than we would be back. Usually, I took up a safe position farthest away from the church door in order to have at least ten yards' start on the rest after one of them had heaved on the bellrope hanging outside the church and let off a great peal in the middle of mass. The temptation grew to clang it myself.

One evening, with the rest watching me and keeping an eye on the transept door from which Kenny would inevitably appear, I took a grip as high above my head as I could, heaved, and heard the echoing, discordant note. Then, before I could release myself, I was being pulled up, soaring feet off the ground with the recoil. I was still hanging in the air when Kenny arrived. Half pulling, half lifting me down, he laid me across his knee and gave me the biggest hiding I had experienced since a boy called Fergus had pulverised me in the schoolyard. Yet it was my pride, not my backside, that hurt most. To my surprise, I was more popular with the other boys, both in choir and school, after that.

Ten minutes' walk from our house, across the canal, the town broadened out into fields, acres of them, with only scattered houses and apple orchards. We took to raiding these and then ran for it, and although we were never caught I always felt that I was the most conspicuous because of my size. This also applied in street football. The police would descend on us in twos, but they hadn't a chance. We knew the side streets better than they did. It became trickier when they were mobilised on bicycles, and the summonses that resulted in fines of half a crown or five shillings were regarded as a real disgrace in the neighbourhood. Mothers fondly imagined that their sons could not possibly be involved, and that it was something that could happen only to rougher boys.

Despite these escapades, my closest friend at this time was my cousin Joe Clarke, my mother's sister's son who lived over on the north side of the city. I used to look forward to his visits, and sometimes we would save up fourpence and go to the pictures together.

One Christmas, we were given an airgun between us and, after regular orders to be careful in its use, we took it out one day towards the open fields. On the way, I spotted a man walking up the street some fifty yards away. I said, "Watch this!" I took aim, all the time thinking that the gun wouldn't fire so far, and then pressed the trigger. The man staggered, clutching his head. I thought I could see a big lump coming up on the back of his skull. I was terrified, and so shaken that I turned away, unable to stand the sight. Joe went white, and not a word did he say all the way home. We said nothing about it there, either, and as far as I remember we never used the gun again. It was like having killed somebody, and I kept thinking that if the man had turned round I might have robbed him of an eye.

Although I had been getting about more with the boys, I was still shy - and I loathed school. At thirteen, I had made so little progress that my teacher invited my father to the school and there was some talk of my leaving. My father would have none of it, however, and it was agreed that I should be kept back in the same class for a year. What happened after that depended on me: unless I won a scholarship, I would have to leave or, if I stayed on, my education would no longer be free.

Coming back after the holidays, we found we had a new teacher, a great giant of a man at least six foot three inches tall with snow white hair and a fierce countenance, whom we called The Badger. Brother Madden was his name, and he instantly struck terror into my heart. A firm disciplinarian, he gave the impression that he could read one's innermost thoughts. When he left the classroom he would say: "I'll be gone ten minutes, but I'll know everything that's happened." I believed him.

Soon Madden formed a scholarship class, and as only a handful of awards was available, I was neither hopeful nor interested. My father constantly drove home to me the consequences of leaving school, and his greatest argument was that I would finish up "as a messenger boy and nothing else." This did not unduly alarm me, but Madden did. After that first year under him, I finished second from the top of the class instead of my usual position near the other end, and my languages had improved beyond expectation. Even in Gaelic I came out high.

Madden put me in for a scholarship, and I got through. It took the form of cheques made payable to me from Dublin Corporation for school fees and the cost of books. When the first one came, I made a great play of endorsing it for my father. I felt that I was earning money.

I was now studying hard and also writing a lot of poetry, of which I was proud, and I was even more inclined to shyness than before. One morning, I turned up early for school and there was still ten minutes to go before classes began. In the main hall, some slight contretemps arose between me and another boy, a flame-haired Dubliner as big as myself but with a temper and a more fluent tongue, and soon we were having a slanging match. He raised his fists menacingly, but I didn't think he really meant any violence until he caught me with a tremendous right swing on the chin.

I thought the roof had fallen in. I hit the floorboards, and was too shocked to do any more than pick myself up, and too terrified to consider retaliation. He threw me a contemptuous look, and felt his honour had been saved. This one-sided one-rounder troubled me for the rest of the day and, as I was going home, I saw Sean Tallon also leaving, swinging his satchel. If I had been as much of a fighter as Sean, the redhead would never have risked going for me like that - and, sure, he would never have gone for Sean, big as he was.

I had tried to pick up hints by watching Sean's schoolyard fights, but nobody would take him on any more. I had heard, though, that he boxed in official competitions under the Queensbury Rules, and when his next contest came up I went to see him. Next morning, I was talking to another boy about the way Sean had boxed, and he suggested that we might join the St Andrew's Boxing Club together. It was there, he said, that Sean had learned to look after himself.

It was sixpence a week, and I went to the basement club in York Street three nights a week for lessons and practice. I learned to hit back when I was hurt. I learned how to take a punch without running away. And when I was sixteen, pressing seventeen, the club entered me for the County Dublin Juvenile Championships. At school, I said nothing about my new interest. Somehow, I reached the finals of the 10 st. 7 lb. division - and won the title.

The morning after our teacher, Brother Carew, a rocklike little fellow with a sharp wit, came into the classroom and picked up a newspaper from his desk. One of the boys had put it there with a pencilled ring round a paragraph recording my boxing win. He scanned the class with that rangy look of his, settled his gaze on me in the back row and observed gently: "Well, it may not be able to talk, but obviously it's able to move."

This brought a gust of laughter from the class.

Carew was a mathematician and, with Brother Macauley, he shared the job of knocking the final edges off us before we set out into the world. Macauley was quiet and cultured and a great one for literature who spent a lot of time reading Horace. He encouraged me with my poetry, and when I showed him my latest piece, he was so impressed that he suggested that he might show it to Francis MacManus, who besides being one of our lay teachers, was also a novelist of some distinction. "I think we should get a professional opinion on it, Eamonn," he said.

He took the manuscript, and made an appointment for me to see MacManus. I waited outside the door, and MacManus came out holding my great work in his hands. He looked straight into me and then, offering it back, said: "Tell me, son - do you always suffer from a pain in the belly?" The remark stung me, but I left without a word.

Macauley's kindness seemed to have gone astray, and I was to let him down again quite soon. He liked my essays, and we had just been set to do one on The Seven Ages of Man. Eager to show off his class to a school visitor, Macauley pointed to me and said: "Eamonn - stand up and read your essay, will you." I noticed the wry looks around me, and as I began reading someone hissed, "Sissy!" and when I glanced up again other mischievous grimaces and unreportable remarks were made. Towards the end of the third page, it became too much for me. I said, "Oh, hell!..." and sat down.

This was the first time I had spoken in public. It did not augur well, but at least it made it all too clear that I must conquer my shyness and the effect it had on other people. I started taking part in school plays, attended the optional elocution class, joined the debating society, and took up physical training, which was also an extra subject, outside the curriculum.

Most of the time, we marched around the yard swinging clubs, and I enjoyed it mostly for the companionship of John Ohle, a long-faced boy with prominent teeth. He could wag his ears like a rabbit, and he spent weeks teaching me how to do it. Because of his front teeth formation, he could also whistle without moving his lips. This he did while we marched around, and it drove the drill instructor into a frenzy. Looking for the culprit, the instructor would fix me with a withering look because I was closer to the source of the sound than anyone else except the blank-faced Ohle himself, and I would be going blue in the face with guilt hysteria.

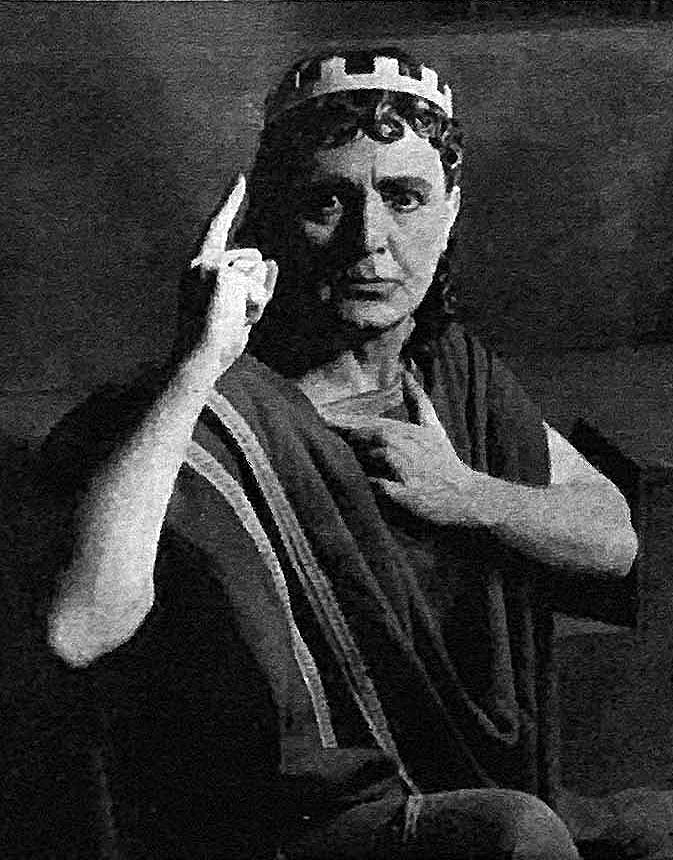

Our elocution teacher, Ena M Burke, appeared to find me too repressed. While others shone in solo recitations, I was self-conscious and came out with the words flatly and in a hurry. In one school play she put on - Tir na n-og, The Land of Youth - I played the king on his throne, as the warriors and courtiers came to pay homage. Inevitably, I lost my lines and Miss Burke had to climb onstage to the foot of the throne to put me right.

In the debating society, I forced myself to my feet to speak, and found it at first a terrible ordeal. Many of the debates fastened on the partition of Ireland, a favourite subject, and it was also fashionable to advance the most outrageous theories, the idea being to twist an established fact or truth into reverse and try to rationalise it. When I was auditor, or president, I took as my end-of term subject the idea that the young man leaving school or university should start work on the top salary scale, perhaps £5,000 a year, and get less as he grew older. That way, he would have the money when he most needed it to buy a house and look after his wife and family.

I never shone in the debating society. I was too introspective and too moderate politically for that, and my real interests were literature, boxing and, increasingly, the theatre. A group of us, including Joe Reynolds, who is still busy writing in Ireland, and Michael Mawe, who had an obscure style of writing and was way ahead of his time, met in each other's homes to discuss writers and plays.

We took to going regularly to the Gate Theatre, where a company inspired by an Irishman, Michael MacLiammoir, and an Englishman, Hilton Edwards, was making a fine reputation. Gallery seats cost ninepence, and I never noticed how hard the wooden seats were. It was a varied repertory: Shakespeare, the classics, modern commercial plays. I came to love the theatre as never before, though for years my father had been deeply concerned with amateur productions, first as an actor, then latterly as a producer. Sometimes on Saturday mornings I had gone down with him to Clarendon Street Hall, a social club attached to the church, through the billiards room where all the tables were occupied, and into the rehearsal room. Always, I felt strangely embarrassed seeing my father studying his lines up there.

MacLiammoir and Edwards rooted my theatre interests and I thought of forming a drama group myself as a vehicle, primarily, for the plays I intended to write. Life was now hectic, for as well as boxing, I was also working for my honours leaving certificate. There was talk at home about the possibilities of my going on to Dublin University, but I was more interested in getting a job and studying in my spare time.

Every night I scanned the situations vacant column of the Evening Herald. It came down to a question of taking a job on the strength of such qualifications as I had, or sitting more examinations for the civil service or Dublin Corporation. At this time, while I was still at school and looking for a job, I qualified for the finals of the All-Ireland amateur boxing championships which were to be fought out at Portlaoighise.

My uncle now had a car and he drove us - Mother, Father, my aunt and myself - the sixty miles to the hall. At the entrance my mother suddenly changed her mind about watching me, and insisted on waiting outside. Even as I climbed through the ropes I kept thinking that she must be feeling cold out there, and that she was probably praying for me. I won the fight on points, and when I rejoined my family in the car my mother's look of relief changed to concern as she spotted the blue swelling near my right eye. My father and my uncle were cock-a-hoop, but Mother said: "Eamonn, it is really time you gave up this sort of thing."

In fact, my boxing successes gave me two fresh ideas about work, I wrote an article for the Evening Herald about training for boxing and, although the sports editor knocked it around a bit, it was published.

It also occurred to me that with the boxing experience and the elocution lessons I had taken I was a ready-made boxing commentator for Radio Eireann. I applied, and was called for an audition to the studios just above the General Post Office - but I heard nothing more. I kept up the search for work, and one night an advertisement appeared for a junior clerk at the Hibernian Insurance Company. I got the job - at £60 a year.

Even in the first week, when the novelty should have had some appeal, I found the work irksome. I had to sit all day long at a desk in front of the underwriters and policywriters, and when a client came in I had to go up and say, "Yes, sir, what is it you want?" When he had told me, I passed him over to the official concerned. This lack of real responsibility infuriated me. It was also impressed upon me that my appearance was important, and I realised that it would not be well received if I were to turn up the morning after a fight with a scar or a half-closed eye. Temporarily, I cut down on the fighting.

With professional examinations coming up, I was studying such books as Principles And Practice of Fire Insurance and Principles of Indemnity, but I found literature and the drama much more interesting and though I had a thirst for knowledge, it was not knowledge about insurance that I sought. I enrolled for an external course with Dublin University, taking a strange selection of subjects – English, Latin, Spanish and logic.

I was still turning out poems in the evenings and still meeting that group of friends who shared my interests. We had talked for some time about forming a drama group. Now it materialised. We discovered that we could hire the town hall for £10, which could be produced from a whip round among our families, and characteristically, for we were very much under his influence, we opened with one of MacLiammoir's plays.

Then came Night Must Fall. This proved to be a great triumph of ignorance on my part, for I played Danny, who is hardly ever offstage from curtain to curtain. I did not understand the character properly and, to make it worse, I had to sing "Mighty Lak' A Rose." In my days with the choir, I had usually got away with it by not singing very loud; now I was solo, and I could hardly sing a note. Through luck and the generosity of the audience, I carried it off.

Afterwards, my father turned up in the dressing-room with a friend, none other than F J McCormick. This great actor with the soft voice and twinkling manner complimented me on my performance. "I was fascinated with it," he said. All through, I had felt like a child walking along a precipice, yet here was McCormick saying it was good. Years later, McCormick was to steal Carol Reed's film, Odd Man Out, as the old man with the birds; and, tragically, he was to die just a week after the picture's release.

To try to improve my acting, I joined the Gaiety School Of Acting run by one of Ireland's greatest actresses, Ria Mooney, who was to become the Abbey Theatre's producer. Despite Ena Burke's coaching, I was having a lot of trouble over some words, especially those with a "u" in the middle and I tended to add syllables, saying "filum" for "film". Ria found all this thoroughly exasperating, but she included me in Crabbed Age and Youth, the shorter of two plays she was putting on at the Gaiety Theatre. Several times she pulled me up about my pronunciation.

At the dress rehearsal we reached a point in the play where a lady faints with her daughters and their suitors around her. As one of the suitors I had to take charge and shout, "A glass of water - quick!" This was followed by several pages of dialogue, by which time the lady had come round and I had to call for a cushion. When I got to the word "cushion", Ria put her hands to her head and excitedly remonstrated: "Cushion, Eamonn. Cushion, cushion, cushion." I had sounded the vowel as in luck instead of in look.

Eventually I managed it - with a desperate tongue contortion.

On the night of the play, we were approaching the waiting scene, and I was standing in the wings, and this cushion business was playing on my mind. I gagged about it to another actor next to me, and stood there repeating in a defensively comic fashion: "Cushion, cushion, cushion." Then the lady fainted, and I made my entrance, and it was a glass of water I should have called for. But I said: "Get me a cushion." The rest of the cast alertly skipped four pages of script and Ria dashed about backstage in an effort to repair the damage. It was no good. I had fouled up the play, and nobody needed to tell me.

After that, I gave more time to the Principles And Practice Of Fire Insurance.

I was washed up as an actor. Yet I hated being a junior clerk, and my lack of interest was evident to my father, who remarked on it several times, as it must have been to my superiors at the Hibernian. Then, one morning when I was shaving, my mother called upstairs to say that there was a letter for me. I ran down, and asked her to open it as my hands as well as my face were covered in soap.

It was from Radio Eireann, and I was being offered my first boxing commentary from the National Stadium, Dublin. I was nineteen, and the world was an oyster, and Dublin was bathed in early morning sunshine as I cycled down to the office. Nothing could stop me now, I thought, and I was so full of the wonder of it that I went through some traffic lights at red.

It never occurred to me that as a broadcaster, as in most other things, I was as green as the Shamrock itself.