Big Red Book

Celebrating television's This Is Your Life

14 April 1956

a brief biography

The Legend That Was Eamonn Andrews

a celebration to mark the presenter's centenary year

first-hand recollections

the producers who steered the programme's success

I brave the fury of Gilbert Harding

by EAMONN ANDREWS as told to Wilfred Greatorex

When he fidgeted and fumed on the panel, I knew that he was preparing an onslaught. In the battles that followed I sided with the challengers – and often became the target.

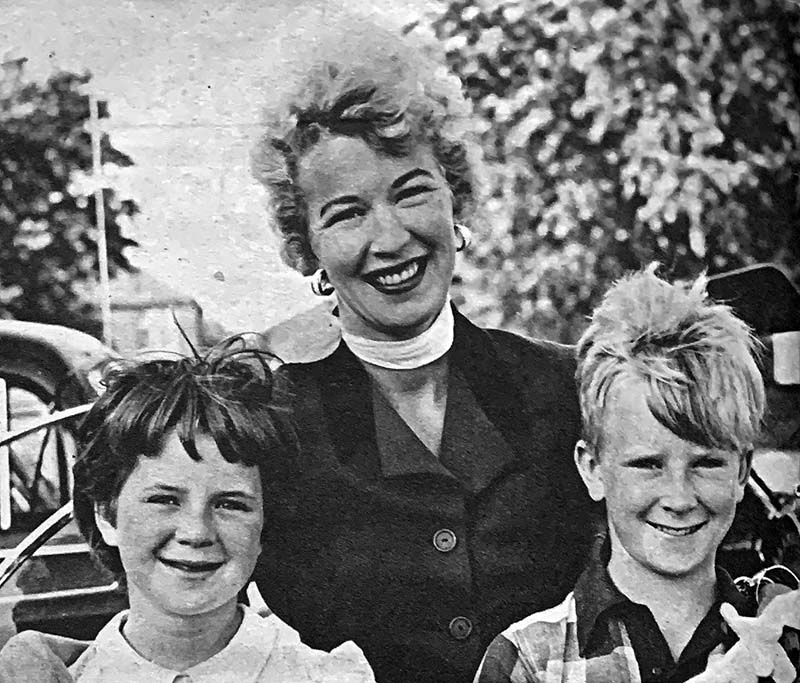

Late in June, 1951, when my affairs had suddenly taken a turn for the better, I found myself Dublin-bound over the Irish Sea yet again - this time with a proposal of marriage on my tongue. Over the previous two years my friendship with Lorcan Bourke's lovely daughter, Grainne, had developed into a long distance courtship spaced by my efforts to break in to the BBC in London, and there had been times when my prospects looked bleak enough to rule out matrimony.

Now, however, I had a useful income from outside broadcast commentaries, occasionally as many as three Saturday sports programmes and a Festival of Britain show called Welcome Stranger. And in the middle of May had come the biggest week I had known as a broadcaster, when six mornings of Housewives' Choice had pushed up my earnings in that week to £100.

It was exceptional, and I knew it, and only when Grainne arrived in London to see me after a holiday in France with her cousin Maureen had I made up my mind to take the plunge. Even then, I saw her off from London Airport without mentioning marriage.

I still felt more like a guest of the BBC than a part of it, and for the first day or two Housewives' Choice had only emphasised this feeling of not belonging. Doing disc programmes for Radio Eireann, I sat down with a couple of turntables beside me, said my introductions and then dropped the needle. Housewives' Choice seemed much more impersonal: everything was done by remote control, with one man on the panel and another putting on the records.

I felt uncomfortable until I realised that it allowed me to concentrate much more on the audience; even so, I missed that exaggerated and heady feeling, experienced by disc-jockeys working for less elaborate stations than the BBC, of having discovered the composers, musicians and singers featured on the records.

On landing at Dublin Airport, I took a taxi to my mother's home at Fairbrother's Fields, tidied myself up, then set out for Grainne's. I borrowed Lorcan's car and drove straight for the most romantic spot I knew in the Dublin Bay area - Howth Head.

It was a warm evening, with only a faint breeze coming in from the sea. We walked along the beach, and I began ham-fistedly explaining to Grainne that I was in a job where at best there was very little real security. From the look she gave me I guessed that she was thinking this was just another bachelor Irishman's blarney. I proposed.

Back at Grainne's we broke the news, and I added boldly that I didn't believe in long engagements. Lorcan produced a bottle of champagne, and it wasn't till two in the morning that I got back home. Later that day I was off back to London, as happy as I had ever been in my life, but determined to pursue more and more work.

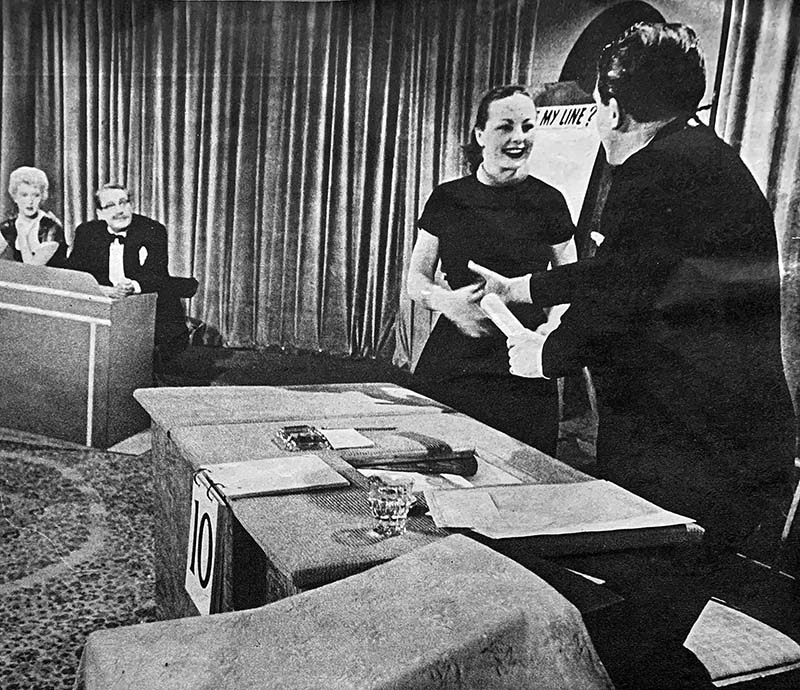

As it turned out, the biggest break I had ever known, though it didn't look like it at the time, was just round the corner. When Ronnie Waldman telephoned to say that the BBC had been considering an American programme called What's My Line? and that my name had been mentioned as a possible chairman. I showed about as much enthusiasm as a man with an appointment to see the dentist. I frankly couldn't see it amounting to anything. I readily agreed, though, to attend a viewing session when several of us who were being considered for the show would be able to see a film of the American version.

At Alexandra Palace I took my seat in the viewing-room along with Gilbert Harding, Robert MacDermot, Barbara Kelly, Bernard Braden, Bill O'Bryen – representing his wife, Liz Allan – Ted Kavanagh, Marghanita Laski, Ronnie Waldman, Maurice Winnick, who held the lease in the show, and Leslie Jackson, who would be its producer. The plugs for a deodorant struck me more than the programme itself.

Afterwards we talked it over in a pub, and a few days later I was advised that Gilbert and I would alternate as chairman. I was billed to take the first programme, a move that led one senior BBC television executive to ask Ronnie Waldman if he was trying to wreck the programme at birth.

There was nothing momentous about our debut, made without fanfare, but the press criticisms were hardly favourable: one writer remarked that I treated the "so-called experts" as if they annoyed me.

It was the following week, when I was doing another job at Skegness, that the first furore broke. Somehow the last two challenges were sent into the studio in the wrong order, and Gilbert, as chairman, found himself at odds with a panel beater whom he innocently supposed to be a male nurse.

Asked if he had anything to do with transport, the panel beater answered, "Yes."

"No," Gilbert corrected, thinking of the male nurse.

At such cross purposes the conflict went on until Gilbert announced: "He's a male nurse."

"No, I'm not. I'm a panel beater."

"Oh, are you?" said Gilbert, huffily. "I don't know what the devil's happening, but this is the last time I shall appear on TV."

It was the first sensation in What's My Line? - the first Harding broadside to rock the nation. I came in as chairman of the third of the programmes, and stayed, though the panel was frequently changed and new gimmicks were introduced - the quickie challenge, mimed clues and certificates for those who achieved ten noes to the panel's questions.

My problem as chairman, after determining to interfere as little as possible, was to make up my mind exactly where I stood. I was also learning that it was unwise to wisecrack when viewers were getting an eyeful of Barbara Kelly; this only infuriated the male members of the audience.

My sympathies soon slipped over to the challengers. Almost without exception they arrived at the studio cockily eager to beat the panel, and with an immense pride in their jobs that made me marvel.

One of my first jobs was to check such points on the challengers' cards as whether or not they were self-employed. I was doing this with a shoeshine boy when he suddenly pulled me up. "What's that you said about it being unskilled? Don't start that."

"I'm sorry," I said. "Of course it's skilled."

I was learning. In all the hundreds of What's My Line? programmes over which I have presided, I have come across only two people who openly claimed that their jobs were unskilled.

In spite of this pride I noticed a subtle change in the attitude of challengers as transmission time approached. From assurance their manner fell away into nervousness and at times sheer dread. It occurred to me that the whole game placed one man or woman unaccustomed to the lights, cameras and the other terrifying paraphernalia of a TV studio against four professionals who were used to these things.

I decided to weigh-in with the challengers. I started talking about "this side of the house." It made me fair game for Gilbert Harding. If he considered the challenger's answers evasive, Gilbert fired and flamed like a jet engine and launched into the rages and Cromwellian broadsides for which he became famous.

Sometimes, he assumed that the challenger was saying more or less than the truth. When in fact he was not, Gilbert let me have it too, and I was the only one besides the challenger who knew the facts of the matter. The man who interferes to settle a row usually gets hit the hardest, and soon my mental imagery made him look more like an opponent sitting poised in the other corner of a fight ring. I watched him before each programme like a schoolboy searching his master's face, wondering if he had a good dinner inside him or was merely suffering from indigestion.

It was impossible to forecast the storm clouds. Once or twice, when the programme preceding ours overran, I knew the witches' cauldron had been stirred as Gilbert fidgeted and grumbled under the hot lights. Twice we left the studio after the programme without speaking to each other.

The first time this happened followed my application of the word "luxury" to muffins. Gilbert thought this was nonsense. By such small things are quarrels born. In the reception room afterwards he stood with his drink in a corner addressing remarks meant for me to everyone except me.

Gilbert's irascibility engendered a high temperature among those viewers who became challengers, and increasingly I found myself listening to threats. "I'm going to fix this fellow, you know," some would say. I never bothered to warn them that more than likely Gilbert was equipped with a sharper tongue and mind than they were.

When the cameras started winking, their bluster evaporated. I seldom tried to dissuade them from going into battle. "OK," I would say when a threat came up, "do what you like." I knew they would be more circumspect when the time came.

Through all this many people got the idea that the clashes between Gilbert and me were a put-up job. In truth, they never were: only once, when we had come to understand each other better, did we "needle" for fun or gain. People had come to expect it, and we did a Sunday concert at Luton with a bit of denunciatory cross-talk which went down well. Once, when I was presenting a greyhound trophy at Clapton, someone yelled, "Where's Gilbert?" and I announced, "Don't worry. He's running in Trap 2 in the next race." After the races I was signing autographs and a man asked me to sign on the back of a thick wad of paper, which I realised was a bundle of £5 notes. I gave the man a questioning look and he grinned. "Took your advice. We were all on Trap 2 in that race. It came up."

The bookmakers had a bad night through my remark.

The impact of television, and What's My Line? especially, was coming home to me. I was beginning to understand why agents were so keen to foist their clients on to producer Leslie Jackson for the celebrity spot. In a Regent Street coffee house a waiter spoke to me about the show, and so did two taxi drivers and a porter at Kensington Air Terminal. In a few months my fortunes seemed to have turned full circle and engagements were piling up. Besides radio and television there were concerts, public appearances, and I began what was to become a years-long association with cinema newsreels as commentator.

I recorded these commentaries late at night at Denham, and on Saturdays when special newsreels were being prepared on big sporting events I would finish three sports programmes at Broadcasting House and dash out to Denham for a film-making session finishing at any time up to six o'clock on the Sunday morning.

In addition I was searching for a flat in anticipation of my forthcoming marriage. It was Dorise, the wife of my personal manager Teddy Sommerfield, who found one – at West Hampstead: it was furnished, and Grainne came over with her mother to see it. She was not over-impressed and said that the furniture would have to go. The wedding was on Wednesday, November 7, 1951, at Corpus Christi Church, Dublin, and as there was a What's My Line? on the Monday night, I decided to fly over on the Tuesday. Living in the flat on my own I had purposely bought in little food in view of what would be almost a fortnight's absence. On What's My Line? one of the challengers was a salmon smoker and after the show he presented me with a huge package of delicious looking salmon. I went home and dined royally, alone.

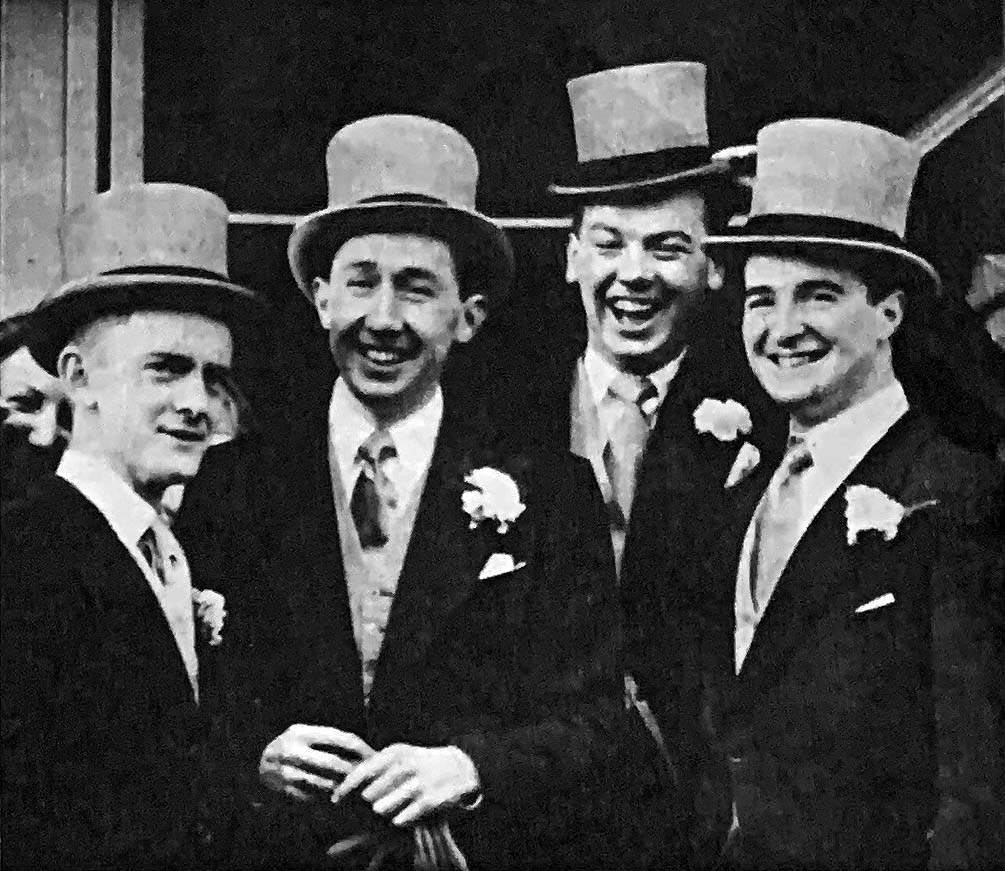

I was nervous about the ceremony - it was at nine o'clock, with nuptial mass - but all went well until we left the church. Accidentally or on purpose, the borrowed toppers worn by the men, who included my manager, Teddy Sommerfield, Brian George, and my best man, Jimmy Shiel, manager of the Dublin Theatre Royal, had been switched while we were signing the marriage register. As we came out to face the photographers, Jimmy gave the instruction that all hats should be worn and not carried for the pictures. Rarely can a wedding group have been photographed wearing such ill-fitting headgear.

Outside, it seemed that half of Dublin had turned out to wish us well, and we had some difficulty in getting away in the bridal car to Grainne's father's place, The Four Provinces, for the reception. As we approached it our driver, Leo, warned that we were early and suggested driving round the side streets for a few minutes. We sat in the back of the car, which was attracting plenty of attention with its white streamers, and I was dying for a smoke. "Have you got a fag, Leo?" I asked.

"I don't smoke," he said, "but hold on." He pulled up outside a pub in Leeson Street, and when he returned he not only had a packet of ten but two whiskies as well. "Drink that, the pair of you," he said. "You must be frozen." Grainne wasn't having whiskey, so I drank both, wondering what all those people staring in at the windows would be thinking about a bridegroom who takes his wife's drink as well.

After the reception, where we had 250 guests, we drove to Parknasilla, which is Gaelic for "the place of the fairies," an almost sub-tropical haven deep in County Kerry on the southern-most tip of Ireland. But at this time of year even Parknasilla was cold and blustery and we were the luxury hotel's only guests.

Every day we drove into the mountains which gave the district an appearance of natural impregnability and its popular title, The Kingdom of Kerry. Coming down the steep road one afternoon in a rainstorm we were hailed by a hiking couple, and stopped to give them a lift. As the man opened the car door he said: "I saw you on TV last Monday, didn't I?" If I needed any further evidence of the staggering impact of television, this was it. Grainne was rather bewildered by the whole thing.

However, once we were settled in London, she soon got the hang of this new-fangled medium, and sometimes after What's My Line? she would criticise me for intervening too much. It was also rather disturbing to find that more often than not she sided with Gilbert. At this time I was almost working the clock round. As well as my other commitments, I took on a night spot engagement at the Empress Club for producer Richard Afton, doing my Double Or Drop quiz for a sophisticated audience which didn't laugh very easily. We decided to have an accumulator prize, starting with one bottle of champagne and building up to a crate of bottles; but Harry Green, the American comedian, won it the first night by answering one of my questions about that evening's news.

I felt more than slightly uncomfortable as a night club entertainer, and after three or four weeks of this work, which began at midnight after a normal day's engagements, I was ready for a holiday. I hesitated to take one, though; for the days when I found it hard to get a single job were not all that far back.

Towards the end of 1952 I was told that Welcome Stranger was to be revived under the title Welcome To Britain. We were not confined to London this time, and for the first programme I had to interview Coronation Year visitors to Britain aboard the Queen Elizabeth. This meant travelling out to Cherbourg in the Queen Mary to meet them, but when we got there the weather was too rough to get us off: we waited for the calm. I hoped that the weather wouldn't break at all, and I imagined headlines such as "BBC Team Carried To States," and the interviews I might get over the other side with all this BBC recording equipment. Unfortunately, the sea calmed enough after several hours' wait for us to be taken off on a tender that bucked wildly.

For another Welcome To Britain programme it was decided to cover the Edinburgh Festival and to follow up with the Braemar Games. In between I had arranged to go over to Dublin for a wedding; I realised that on the return trip I would be cutting it fine and that it meant catching the Aberdeen plane from Edinburgh with only minutes to spare. Shortly before leaving Edinburgh for Dublin, I found myself chatting casually in the airport bar to a neatly dressed stranger who seemed concerned about my problem. When I left to board the aircraft he said: "Don't worry. This is an RAF base as well, you know."

I couldn't see the point then, but on landing after the return trip from Dublin I saw the same man, this time in the uniform of a senior RAF officer, beckoning me. He stood on the tarmac and called urgently: "Come on, quick!" He hustled me into a waiting plane, the steps were pulled up and we were off. I have never met him since, but this man, by remembering a chance conversation with a stranger, enabled me to get to Braemar in time: he had held the Aberdeen plane until I arrived - and I had been ten minutes late from Dublin.

For such unexpected kindnesses, and the insight it gave me into Britain and its people, Welcome To Britain was terrific. We covered the whole country, and on the Isle of Skye I met an old school chum, Seamus Ennis, a folklorist who plays the pipes and can never resist a song. Our base for this programme was a fine hotel in Kyle of Lochalsh, and I was looking forward to staying in it that night. But Seamus was in a typically sociable mood and the evening flickered away with his songs and the tales of an islander who had joined our party.

When I asked about the last boat to the mainland, Seamus said disarmingly: "That's all right. I'll fix it. I'll tell 'em we're a bit late, that's all." Seamus's fixing was a bit Irish, for when the time came to leave there was no boat and I spent the night in an island attic.

In my travels during that summer of 1953 I experienced probably more than most people the atmosphere of the Coronation – and it was in Coronation week that I was faced with my most heart-searching moment since my arrival in Britain.

Shortly before we went on the air with What's My Line? Leslie Jackson, the producer, told us that at the close we would drink a Royal toast. I shared the most loyal Briton's respect and admiration for the young Queen facing her tremendous ordeal, but I was worried about what I should say in proposing this toast. When the champagne came round, I held up my glass and said: "Now we will drink a Royal toast. Here's to your Queen."

Even as I uttered the words I knew that I would be in trouble; but as a citizen of the Republic of Ireland I could not in all honesty include myself as one of the Queen's subjects, nor would it have been right to do so. It would have been blatant hypocrisy.

Nobody at the studios mentioned the matter, though I sensed some feeling, and it was only in the days that followed that the indignation of some people expressed itself in letters.

This moment of inner conflict worried me for a long time, but in the November of that year something happened which implied, to me at any rate, that the Queen herself understood. I was invited to appear in the Royal Variety Performance at the Coliseum. As a member of the world of entertainment, I addressed an epilogue written by Alan Melville directly to the Queen in her stage side box as a huge tableau representing the Commonwealth appeared on the stage. For reasons other than professional ones, it was among the most thrilling experience of my life.

Around this time, Grainne and I crossed to Ireland for the opening of my father-in-law's theatre in Limerick, the rebuilt City Theatre. It was intended as a quick trip prior to what was to be our first real holiday - in Italy. After the opening, when we had returned to Dublin, Grainne complained of a pain in her side. We thought it was rheumatism, but the pain persisted and back in London Grainne went to see the doctor. I could not go with her, as I had to be in Southampton that day for the winding-up programme of Welcome To Britain: interviews with prisoners of war back from Korea. I telephoned her from Southampton, and found she was upset because the doctor had ordered her to go into hospital immediately.

We checked with two specialists, and they agreed with the diagnosis: the hip was infected, and the treatment was likely to be long. We cancelled the Italian holiday, and Grainne entered the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital at Stanmore. I went up there most evenings, and driving back past the Christmas-lighted front rooms of the northern suburbs emphasised my sense of loneliness.

As the weeks went by, I got into the habit of dining in a restaurant after my visit to the hospital; but one day a friend of mine named Bunny France suggested that I should have dinner at his home in Holborn. This coincided with the first time I took our pet poodle, Quiz, to the hospital.

Some months earlier, Grainne and I had been walking along Baker Street when she saw a small black poodle pup in a pet shop window. As her birthday was approaching, I suggested that we might buy it. We went inside and the shopkeeper asked fifteen guineas for it, whereupon we walked out again. By the time we reached the street, the dealer had put the dog back in the window. Grainne stopped for another look, and we were sunk. I bought the pup.

Every time I visited the hospital, Grainne would inquire, "How's the little fellow?" and one night she asked me to bring Quiz next time I called. The ward sister agreed, and it was on the night I was due at Bunny France's that I took him.

Seeing the pup seemed to cheer Grainne and I felt glad that I had taken him. Anne France, who had appeared on What's My Line? when she was an air hostess, gave him some supper, and when we left it was after eleven o'clock and pouring with rain. The windscreen was a blur, and presently I got lost in that dark district behind Euston Station. Pavement-hugging, I spotted a policeman sheltering in a shop doorway and stopped to ask him the way to West Hampstead.

It was getting on for midnight when I reached the flat, and called Quiz to jump out. There was no sign of the dog, and I telephoned Bunny, thinking that I had left him there. Then it dawned on me that Quiz must have leaped out when I opened the door to speak to the policeman. I drove back to the Euston area and after cruising around for some minutes I found the same policeman. "I thought you'd be back," he said. "Your dog jumped out when you stopped."

"He's at the police station, is he?" I asked.

"Sorry," said the policeman. "He was too quick for me. He ran off."

I began patrolling the murky streets, and there were plenty of dogs to see, but no Quiz. Presently, I noticed some headlights in my driving mirror; they got closer, then a police car overtook me and waved me down. An officer came up to my driving window. "Now then," he said, "we've been watching you coasting round these parts for twenty minutes. What's the game?"

Here was a man without a television set who thought I was an unsavoury character planning some night work. But he took my word when I explained; advised me to report the loss to the nearest police station, and promised that he and his co-driver would keep a look-out themselves. I resumed the search, but at three o'clock in the morning my petrol gauge was showing "empty" and I called it off. In a few hours I would begin my busiest spell of the week – three Saturday sports programmes.

I drove up to Stanmore in the afternoon and, sure enough, Grainne's first question was, "How's the little fellow?"

"He's fine," I lied.

Later, the police telephoned me to say that they had Quiz's collar. A man had found him lying in the gutter, had stooped to check his name and address and, being unable to make out the words in the poor light, had removed the collar for a closer look. At this moment, Quiz bolted.

After the last sports programme that evening, I toured the Euston district again. Still there was no trace, and the police station had no further news. It was getting on towards midnight when, passing the cab rank near King's Cross Station, I had an idea. I put my head round the door of the smoke-filled taxi men's hut and told the drivers about my missing dog. "If you'll go out and look for him," I said, "I'll pay whatever is on your clocks, plus tips - and a fiver to the man who finds him." The hunt was intensified.

It was almost three o'clock on Sunday morning when I returned to the flat. I was worrying about the way I would have to break the news to Grainne, for I now despaired of ever seeing Quiz again. When the opportunity came during my afternoon visit, I shirked it and once more told her that Quiz was fine.

That night, Teddy Sommerfield came out to join me with his car. We met periodically to exchange news, but we were out of luck until we again called at the police station, to learn that a man in Gray's Inn Road had reported finding a black poodle. A hefty character answered our knock, and explained that a couple in the flat above might know something about it; but they were out at the pub and would not be back until closing time. We waited in the two cars.

When the couple showed up, the man admitted finding a poodle but asked how I could prove it was mine. "If he sees me," I said, hopefully, "you'll know." At first he wasn't keen, but presently, when I suggested we should talk about it over at the police station, he relented and let Quiz out. He bounded up at me, but the man was still not convinced and we finished up at the police station while the duty sergeant grew increasingly flummoxed in a Robb Wilton way over our squabble. Finally, the finder agreed to hand over the dog. I gave him £5 and, as I was leaving, his wife came up to me looking rather bewildered and asked: "What do you call him?"

"Quiz," I said.

"Blimey!" she said. "We've been calling him Charlie."

I thought it better not to mention the episode to Grainne until she was much better. The weeks dragged into months, and she was still in hospital, and I immersed myself defensively in more work. When I was first given the news that Grainne would shortly be well enough to come out, I decided to find a better place for us to live. It would have to be an unfurnished town flat, which was hard to find; it would also have to be on the ground floor. For I knew that when the day came for me to bring Grainne home, for some time she would be able to walk only on crutches.