Big Red Book

Celebrating television's This Is Your Life

Stephen BEHAN (1891-1967)

- The first edition to be recorded outside the UK

THIS IS YOUR LIFE - Stephen Behan, housepainter, was surprised by Eamonn Andrews in the audience at the RTE Studios in Dublin, from where the programme was then recorded.

Stephen, who was born in Dublin, was an amateur footballer in his youth before spending time as a novitiate with the Jesuit Fathers. As a republican, his beliefs were at odds with the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922, and during the Irish Civil War, he was imprisoned for two years in Kilmainham Jail.

Having married and with a growing family, he found regular work as a painter and decorator, becoming President of the Irish National Painters and Decorators Union. He is the father of writers Brendan and Dominic Behan, who both credit him with their literary education.

programme details...

- Edition No: 205

- Subject No: 206

- Broadcast date: Tue 4 Dec 1962

- Broadcast time: 7.55-8.25pm

- Recorded: Mon 19 Nov 1962 7.30pm

- Venue: RTE Studio 1, Dublin

- Series: 8

- Edition: 10

on the guest list...

- Brendan Behan - son

- Chrissie Richardson

- Jimmy Watson

- Kathleen - wife

- Dominic Behan - son

- John Behan

- Sean O'Sullivan

- Jim Kearney

- Rory Furlong - stepson

- May Furlong

- Sean Furlong - stepson

- Seamus Behan - son

- Mrs Seamus Behan - daughter-in-law

- Josephine Behan

- Pearce Kearney

- Mrs Pearce Kearney

- Con Kearney

- Massie Kearney

production team...

- Researcher: unknown

- Writer: Peter Moore

- Director: Vere Lorrimer

- Producer: T Leslie Jackson

from domestic cleaner to teacher

the show's fifty year history

Somewhere, Someone - This Is Your Life

Talk of Thames feature on the programme's 1969 relaunch

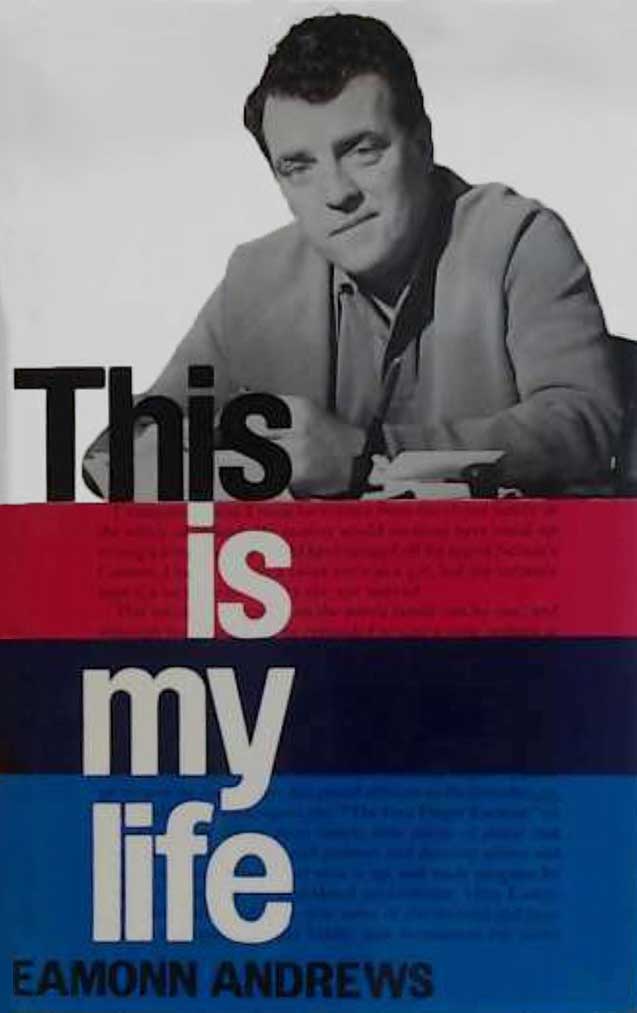

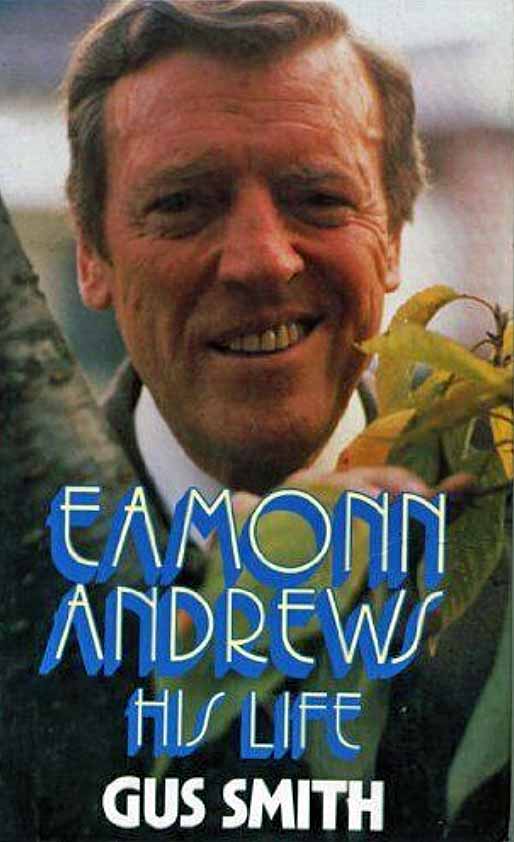

RTE Guide tribute to Eamonn Andrews

Photographs of Stephen Behan This Is Your Life

Since This Is Your Life began, certain names have automatically suggested themselves. Certain film stars for example would obviously make good, interesting programmes. Indeed, almost any name that captures the public imagination is at one time or another considered as a possible. Such a name is Brendan Behan. But as with many that seem stand-out choices, Brendan's always gave us pause. He was so utterly unpredictable.

On and off, whenever he came under discussion, great enthusiasm was generated. But there was always fear, too, and the project would be shelved. Brendan appeared on an interview programme with Malcolm Muggeridge, but was so obviously and self-confessedly pickled as to be almost unintelligible. Then there was a little affair with an Ed Murrow programme which was equally ineffective as a sales vehicle for the Behan talents.

I have a great admiration for him as a writer and as a person. I knew he'd got a "terrible tongue", but at least it is a fault that is obvious. Most of us have faults that are hidden. Fred O'Donovan in Dublin had the idea of trying to do a filmed interview with him, as he was sure it would make good entertainment. Main thing was to get him sober.

The interview was eventually set up, and I flew across from London to Dublin, met Lorcan Bourke, my father-in-law, and drove out to the Behan house at Ballsbridge. We were to take Brendan out to a hotel in Bray, close to the Ardmore Studios, so that an early start could be made the following day. There was a light misty rain falling over the city as we drove to Brendan's place.

When we knocked at the door, out came a figure with a great mop of hair falling around his eyes, sleeves rolled up to the elbow, and shirt front open down to the navel.

"Hello, Brendan," I said, "Are you ready?"

"I'll be with yez in a minit," he said, and slammed the door in our faces.

Standing on the street in the cold and wet, I turned to Lorcan:

"Well he's your relative," I said, "not mine. What are you going to do now?"

"Let's sit in the car," Lorcan mumbled, "we're only getting wet standing here."

We were just about to get into the car when the house door opened again. Brendan was standing there.

He said (and from here on you can insert any words you like wherever I leave a gap, Brendan's choice of adjectives and adverbs is pretty wide): "Whay don't ye _____ come in?"

"It's very hard, Brendan, to come in through a slammed door."

"Ah I was only tryin' to keep in the ____ cat."

We went in, and one thing I remember distinctly is that there were piles of monkey nuts on the sideboard. Standing at the fireplace was an unshaven character who was introduced as an artist, and on the settee in the middle of the room was a threadbare overcoat, at the top of which, was, presumably, a head, because there was a peaked cap atop the lot. Then I saw a bottle of stout being held from one of the sleeves. And underneath the cap a red nose was flashing. Perhaps glowing is a better description.

"Are you coming, Brendan?" I asked.

"Oh Beatrice is packin' the bag," he said. Then he turned away and yelled: "Have ye got the ____ bag packed yet, Beatrice?"

A gentle voice floated down the stairs: "Just a minute darling."

Brendan produced a half-bottle of Irish whiskey, and two champagne glasses. He handed these to Lorcan and me and poured whiskey in them.

He turned to me an apropos of nothing said: "Fame is a great ____ thing, but you'd know all about that, on the ____ television."

"What do you mean, Brendan?"

"Well, I came home today in a ____ taxi, and when I got here the taxi-driver wouldn't take the ____ fare. He recognised who I was. Marvellous."

"Well, that's great, Brendan," I said, "I'm delighted you've got recognition at last."

He went on for some time about the taxi-driver, dwelling eloquently and luridly on the marvels of being recognised and having no fare to pay.

Then Beatrice, Brendan's wife, came into the room with the bag packed and ready. Before we went out, Brendan, who was very generous, picked up the whiskey bottle in which there was still quite a lot left. He walked over to the overcoat on the settee, opened on of the pockets, and pushed the bottle in. "There you are, Mick, that's for you."

The overcoat struggled into a wobbly standing position, and the mouth of its inhabitant opened in an effort to say "Thank you". But no words came out whereupon the overcoat relapsed into a reclining position again, and finished its bottle of Guinness before rising once more.

On our way out to the car, I was at the end of the convoy with Brendan. I was curious about the overcoat. I touched Brendan's shoulder, gestured with my thumb and whispered: "Brendan, who's Mick?"

"Oh, him?" said Brendan, "He's the ____ taxi-driver."

Believe it or not, we succeeded in making the film the next morning. There was a jug of Guinness hidden out of shot, and when we had to reload the cameras we reloaded Brendan, too. In fact, he was a perfect, sober, entertaining and philosophical interviewee. But we never did try to get him for This Is Your Life. Instead, a couple of years later we picked his father – Stephen Behan, a roguish, talkative, witty housepainter. This decision lessened but did not remove the problem of Brendan. Producer Leslie Jackson had no doubts: "We cannot do the programme unless we have Brendan in it."

The snag was that Brendan was "taking the cure" somewhere in the South of France. Finally we tracked him down, and from a hotel in Newcastle I talked to the "Quare Fella" and told him what we were proposing to do. Back over the Continental line crackled Brendan's voice. "Yeh, yeh, a great idea. How much is the ____ fee?"

Having got over that one, he asked me to call him back next day and spelt out the telephone exchange of where he would be. I wonder in how many junction points across Europe there were blushing English-speaking telephonists. All I can say is that Brendan did not use the standard identifications for clarity – F for Freddie. A for Apple. S for Sugar. Nevertheless, I was quite clear which exchange he meant.

Arrangements were made to get him back from France in time for the programme. The next thing I saw was a newspaper photograph of him disembarking from a plane, hand clutching an ominous-looking bottle. The heart sank inside me – the cure obviously hadn't worked for Brendan.

Jacko got him in tow and escorted him to Dublin. I was to follow on a later flight. When I got there, forebodings were borne out when Jacko told me that Brendan had vanished. We ran him to earth finally, holed up in a cold room with Des MacNamara, a distinguished sculptor, and a bearded writer. Scattered around were half-empty stout bottles, but no bedclothes, not a crust of food.

As soon as he laid eyes on me, Brendan opened up. Again it was apropos of nothing I could see. "There was ould women with string bags at your weddin', but my bloody mother wasn't invited."

I said: "Now, Brendan, we've got a programme tomorrow. You're talking about something that happened nearly ten years ago."

Eventually we made peace, and the clock moved steadily on into the morning. By the time the half-empty bottle of stout became empty he agreed to go to a hotel if we could get him into one. A shrinking market, I'd say. Jacko, however, persuaded the night porter at his hotel to accommodate all three.

Next day he vanished again, was reported to us as sleeping at about three o'clock, and eventually turned up at the studios at 6.30pm. He persisted in rambling around, scaring all of us in case he ran into his father and gave the whole game away. I tried to get into his head to say something about his father when he came on the show. Oh, he'd say something all right – and he proceeded to dish out a stream of Rabelaisian stories which he threatened to tell. Terrifying. It was almost programme time.

"Ah go on, go on," Brendan said to my pleading, "I won't let you down at all."

It was to be an audience pick-up; the subject would be in an audience, many of whose stories the programme could obviously be telling. When I got to where Stephen Behan was sitting, I could see him staring up at the monitor screen above his head. In the picture he could see himself, with me standing close by.

I said: "What's your name?" We had never met.

Without turning to me, still trying the fathom the mystery of seeing himself in a picture looking at himself in a picture, etc, etc, he just said "Behan".

I said: "Are you anything to Brendan and Dominic Behan?"

He could see me too in the picture, so now he looked down for a moment, flicked his eyes towards me, and then shot them back to the monitor to see if it was the same fellow standing alongside and talking.

Then he answered the question. "Yeah, I'm married to their mother."

Next I asked a question which I knew what the answer would be. It would be "Me, of course."

I said: "When Brendan comes home, who does all the talking?"

This puzzled him. As if it were a stupid question. "Hah! Their mother," Stephen said. The audience roared.

I sprang the surprise on him, helped him out of his overcoat and got him to the chair of honour. The first spot on the programme was to be Brendan. On he came, looking encouragingly spruce. After he had sat down, and to get things away to a smooth start, I asked him: "What are your father's outstanding qualities?"

He ignored me completely. He looked beyond me, down to where the studio audience sat. He said: "That's Tony O'Reilly down there, the rugby player. D'ye know him? I played soccer with that fella once."

He elaborated on that. We had now lost two and a half minutes of programme time, and the whole thing looked like tumbling down.

"It's your father's life you know, Brendan," I said "tell us about him."

"Oh, I'll tell ye about him."

He sat down and pulled out a packet of French cigarettes. He offered one to Stephen, then one to me.

"No thanks," I said.

He lit his own. "I suppose you can afford better ones, with all this television, hah?"

From that point on it was hilarious, but hardly relevant. Father and son warmed to the situation. How I got Brendan off I've no idea, but eventually he shuffled off, leaving some of the audience horrified and some hilarious. Then came Stephen's wife, Kathleen, Dominic, friends, relatives. The latent actor in all Dublin people came out, all preconceived ideas of a timing schedule went haywire, and everyone save me had a ball.

One little incident which viewers never realised but to which I was a helpless witness concerned Stephen's pipe. Stephen and the pipe were inseparable. It was part of his character. But when I helped him out of his overcoat in the audience, the pipe was left behind in the top pocket. When this was realised, Peter Moore, the writer, slipped down, recovered the pipe and the little brown paper bag of baccy that nestled with it in the pocket. Thus when one of the later guests in the show came on, the pipe and paper bag were handed over again to Stephen.

But the man who did the recovery job clearly wasn't fully aware of the habits of the Dublin working man. You see your Dubliner often carries two such paper bags with him, one containing tobacco, the other a mixture of sugar and tea for the billie-can. The wrong bag was handed to Stephen. I knew it as soon as I saw the puzzlement on his face as his fingers dealt with the strange-feeling mixture which he was trying to stuff into the bowl of his pipe. All the way through, I could only stand and watch as poor old Stephen tried to get his pipe going on sugar and tea.

Although Eamonn had coped confidently with Brendan (Behan) in the filmed interview he still was reluctant to have him as the subject on This Is Your Life. Apart from his unpredictability, he feared he would steal the limelight from everyone else on the programme and that was something he had tried to avoid, even in his own role as presenter.

Eventually, when it was decided to hand the large Life book to Brendan's father, Stephen, Eamonn said to producer Leslie Jackson, 'We mustn't allow Brendan to upset the show. Can we keep him in check?' Jackson, a seasoned producer, knew it wasn't going to be easy. Brendan could be boisterous if he had too much to drink. When Eamonn met him before the show, however, Brendan promised, 'I won't let you down at all. I give you my word.'

It was decided to pre-record the show at the RTE Studios in Dublin, thereby ruling out a 'live' performance by Brendan Behan, for the programme would not be screened until two weeks later. Eamonn recalled, 'When I got to where Stephen Behan was sitting among the audience, I could see him staring up at the monitor screen above his head. In the picture he could see himself, with me standing close by. I said, "What's your name?" We had never met. Without turning to me, still trying to fathom the mystery of seeing himself in a picture, he just said, "Behan."' The audience looked in Eamonn's direction as he asked the genial old man, 'Are you anything to Brendan and Dominic Behan?'

The audience laughed as Stephen remarked, 'I'm married to their mother.'

Eamonn: 'When Brendan comes home, who does all the talking?'

After a puzzled pause, Stephen said, 'Their mother.'

The audience was enjoying the fun. Just then Eamonn sprang the surprise, but Stephen did not appear to comprehend fully what was going on. When Brendan was announced as the first guest he seemed to ignore Eamonn and, instead, began to talk about Tony O'Reilly. 'D'you know him, Eamonn? I played soccer with that fella once.'

Eamonn did his best to try to steer him back to the programme. 'It's your father's life you know, Brendan. Tell us about him.'

Brendan shrugged his shoulders. 'Oh, I'll tell ye about him.'

Leslie Jackson was on tenterhooks in the wings, wondering what Brendan was going to say and if, afterwards, they would be able to get him off to allow the other guests on. Brendan was acting as though he was in a Dublin 'local' and chatted affably with Stephen, oblivious of Eamonn. The audience by now had entered fully into the spirit of the show.

To Eamonn's relief, Stephen was holding his own and refused to allow Brendan to steal the limelight. Eventually, Brendan shuffled off, muttering to himself. It was the cue for the entry of Stephen's wife, Kathleen Behan, and she quickly endeared herself to the audience, with her witty stories about her husband and sons. There was a spontaneous laugh when she announced she would 'love a bottle of stout.'

Eamonn admitted later that he enjoyed the programme despite the obvious Behanesque hazards he had to contend with. He liked to recall one particular incident which he was to find almost moving: 'I was actually a helpless witness to it. It concerned Stephen Behan's pipe. Stephen and the pipe were inseparable. It was part of his character. But when I helped him out of his overcoat in the audience, the pipe was left behind in the top pocket. When this was realised, Peter Moore, the writer, slipped down, recovered the pipe and the little brown paper bag of baccy that nestled with it in the pocket. Thus, when one of the later guests in the show came on, the pipe and paper bag were handed over again to Stephen. Unfortunately the wrong bag was handed to him. I knew it as soon as I saw his forlorn face. All the way through I could only stand and watch as poor old Stephen tried to get his pipe going on sugar and tea!'

At the party after the show in a nearby hotel the Behans and their friends had one big celebration. As Leslie Jackson would joke later, 'I was glad I wasn't picking up the bill!'

The show again demonstrated that Eamonn was able to cope with the unexpected. Yet he was not able to say, as he left the hotel, that he was prepared to hand the Life book to Brendan Behan, as much as he would have loved to.

When Eamonn Andrews did a This Is Your Life show for Da, Brendan was livid that it wasn't himself that was being honoured.

People said Andrews wanted Da on the show because he was afraid to tackle Brendan head on. Maybe so, but let's not forget Andrews did that famous interview with Brendan some years before. Still, it was a different Brendan now, fame and drink having made him into a much more unpredictable animal. Andrews' decision was probably wise in view of what happened after the show. "Why did you want to interview that old bollox anyway?" Brendan said to Andrews. I told him to ease off, that I admired Da, but there was no stopping him. He was pissed as it was, but then some girls arrived with nips and Brendan invited them to leave the bottle. Andrews then introduced the pair of us to RTE's spiritual advisor and Brendan ran amok. "How the hell can Fr Flat Hat lecture a television mast?" he wanted to know. I thought for a moment there was going to be a digging match. I watched Andrews' face get red as a beetroot as he clenched his fist. I took him by the arm and said, "Remember, Eamonn, we're all from the one family" (He was married to our cousin Grainne Burke by this time). That seemed to appease him, but only just.

When Eamonn Andrews was doing the This Is Your Life show for Da, he rang up Brendan and asked him would he appear on it. Brendan thought he was going to be the guest of honour and he jumped at the chance. "Would a duck swim?" he said. But then Andrews explained that he was only going to be a guest and he went half mad. He eventually agreed to take part, but he brought a crowd of lowlifes with him and they got footless and nearly wrecked the BBC after the show. Andrews wasn't too impressed. (As for myself, I got £84 for saying "Hello Dad" so I was quite happy with myself. For that kind of money, I'd say hello to the Devil himself - with a long spoon or a short one.)

An invitation to appear as a guest on the Eamonn Andrews television show, This Is Your Life, gave him an excuse to return to Ireland and also an opportunity to get back to an atmosphere where drinking was regarded as a way of life and not merely as a pastime.

The BBC programme was to deal with Stephen Behan's life and Brendan was to appear with Dominic, Brian, Kathleen and other members of the family, in the format familiar to viewers of this programme.

Elaborate precautions were taken by the BBC team to keep Brendan sober and he arrived at the studios in good fettle. It was recorded in Dublin and subsequently broadcast from London.

In October, Eamonn Andrews contacted Brendan's cousin, Seamus de Burca. He wanted to feature Brendan's father, Stephen Behan, in the British television programme This Is Your Life. The show's format was the surprise reunion where subjects were lured to the studio unawares, to be serially greeted by as many of the family, friends and acquaintances as could be brought to the studio.

The show was filmed in Dublin and Brendan was invited to participate. He returned to Dublin in an alcoholic stupor. The old animosity between himself and his brother, Dominic, surfaced during the recording of the programme - fortunately it was off-camera. Brendan never really accepted that there was more than one writer or performer in the Behan family. That bitter jealousy which had led him, as a boy, to push his brother Seamus down the stairs at Russell Street screaming, 'She's my granny, not yours', remained unresolved in his relationship with Dominic, all those years later.

His relationship with his father also remained uncertain. Family and friends are quite certain that he loved his mother much more than he did his father. Brendan's memory, in spite of being clouded over by alcohol for much of his life, was long and sharp. He had not forgotten the quarrel on the eve of his departure for Liverpool when he was sixteen. He had buried the axe, but he had marked the spot with care. When he began earning very large sums of money from his writing, he made a point of giving his mother money but rarely showed much generosity towards his father.

Series 8 subjects

Rupert Davies | Kenneth Revis | Sydney MacEwan | Cleo Laine | Arthur Baldwin | Edith Sitwell | Ben Fuller | Robert McIntoshMabel Lethbridge | Stephen Behan | Ruby Miller | Richard Attenborough | Daniel Kirkpatrick | Michael Wilson | Dick Hoskin

James Carroll | Uffa Fox | George Cummins | Hattie Jacques | Sam Derry | Finlay Currie | Phyllis Lumley | Ben Lyon

Bertie Tibble | Zena Dare | Victor Willcox | Learie Constantine | Phyllis Richards | Michael Bentine | Joe Loss | Gladys Aylward