Big Red Book

Celebrating television's This Is Your Life

31 March 1956

a brief biography

The Legend That Was Eamonn Andrews

a celebration to mark the presenter's centenary year

first-hand recollections

I bombard my target - BBC, London

by EAMONN ANDREWS as told to Wilfred Greatorex

First I pelted them with letters; then I sent recordings. But the answer was always the same: my voice was not exactly right

When I cycled from my house in Fairbrother's Fields to the police headquarters at Kilmainham Barracks one winter's morning late in 1945 I was in no trouble with the law, but the way I felt I might have been. Sensing my apprehension, the lanky sergeant of the Garda Siochana poured me a cup of tea and said: "All right. Get it off your chest, lad." I started to tell him about the script that never was.

For some months now I had worked as a freelance broadcaster and journalist after throwing up my job as a fire surveyor with the Hibernian Insurance Company. At first, things had not gone too well, and all my attempts to break into branches of broadcasting other than boxing commentaries had come to nothing. I had cycled almost daily to Radio Eireann's studios in Henry Street, Dublin, seeking parts in plays and offering ideas for quiz and interview programmes. Boxing commentaries were infrequent, and the big narration jobs in plays and documentaries, which I wanted most of all, seemed beyond my reach. Then I was bowled over with an idea: if I could not narrate someone else's script, then I would write my own.

None of my suggestions hit the target until I offered the station a series of crime reconstructions. With this idea approved I approached a superintendent of the Garda Siochana who handed me over to a sergeant in the records department. The sergeant was most helpful and from our research I wrote several documentaries with myself as narrator under the title Casebook on Crime. Then, ironically, other work came up: soccer commentaries as well as those on boxing, and the occasional race reading over the loudspeakers at Baldoyle Racecourse. I was averaging six or seven guineas a week, which was an improvement on the wage I had been getting in insurance.

While the Casebook series was running I was given my own disc jockey programme on Thursday nights - a commercial show sponsored by K and S Pure Food Products. After months of trying to find enough work to keep me occupied I now found myself with too much. I got behind with my Casebook scripts.

One afternoon, I was in the studio rehearsing the sponsored show when an assistant beckoned me over to the telephone. Francis MacManus was on the line, the same man who earlier had been one of my schoolmasters and who had asked after reading one of my poems whether I always suffered from a pain in the belly. He was now features director at Radio Eireann and was handling my crime series. He sounded harassed as he said: "Eamonn, we are programming the next Casebook. What's the title going to be?"

I had not thought of a title: in fact, I had not thought of another crime yet. To admit this would have been futile, so I said, "I haven't got a title for it at the moment."

MacManus persisted. "Tell me what the story is about and I'll try to think of one."

I said the first thing that came into my head. "It's about duplicating keys."

"All right," MacManus replied. "Let's call it The Key or something."

The sergeant of the Garda Siochana was my only hope. I admitted my predicament and, momentarily stumped, he stroked his chin as I prayed that somebody in Dublin Jail was there for having at some time used duplicated keys. He turned up a file with just the case to fit the title. I was filled with gratitude, but he curbed my enthusiasm by remarking casually. "All part of the service." I left thinking that the Dublin police were wonderful.

Even if it meant an occasional complication of this kind, the increase in the work I was getting was just the fillip I needed - and not only because it produced more money. The war in Europe just over, Dublin was busier than ever I had known it: life was moving on to a peacetime footing again and, although Eire had been neutral, the stringencies of wartime had been felt. Now, half-forgotten faces were appearing daily as the Irish volunteers came home from service with the British Army, the Royal Navy and the RAF; urgent American accents were to be heard in the streets as G.I.s whose fathers or grandfathers had emigrated to the United States in that great trek over the years came to see the land of their forebears, and the big commercial houses were moving back into business as trade built up. Dublin was all rush and bustle, and until more work came along I had felt somehow isolated.

At home, I was conscious of my position as the eldest child and once or twice wondered if in coming out on my own I had acted with a correct sense of responsibility. Not once in those first five weeks when the prospects looked dim had my parents remarked on my decision, but when things began to expand my mother did ask one night, when I was flushed with fresh confidence, how long this sort of thing was likely to last. My sisters and brother Noel, on the other hand, seemed pleased to have a broadcaster rather than an insurance man in the family.

Now that I was giving more time to it, I was learning plenty about broadcasting techniques and, of course, the snags caused by ordinary human failings which can so easily upset a programme. In one Casebook feature, my script called for a girl telephoning the police with a message about stolen goods and in this part was an attractive red-haired colleen who was also shortsighted. She was placed near a microphone in a corner, right under the three control lights - red showing that the studio was "live"; green indicating that it was off the air, and amber giving the go-ahead for speech.

When the amber light flickered, the girl was peering at her script. It had gone out when she looked up. She peered at her script again and during this time the sergeant "answered" on another microphone. Once more the amber light flickered, and again she missed her cue. There were four or five mis-timings before the glance and the light coincided and she spoke her lines. Listeners must have thought that the informant had changed her mind about telling the police, or else had an almighty stammer.

Broadcasting is littered with snags and vexations and, paradoxically, it is one of these - a commentary on a boxing match - that was to help me professionally, in an indirect way, more than any other job I had done either as a side-lining beginner or as a full-time freelance.

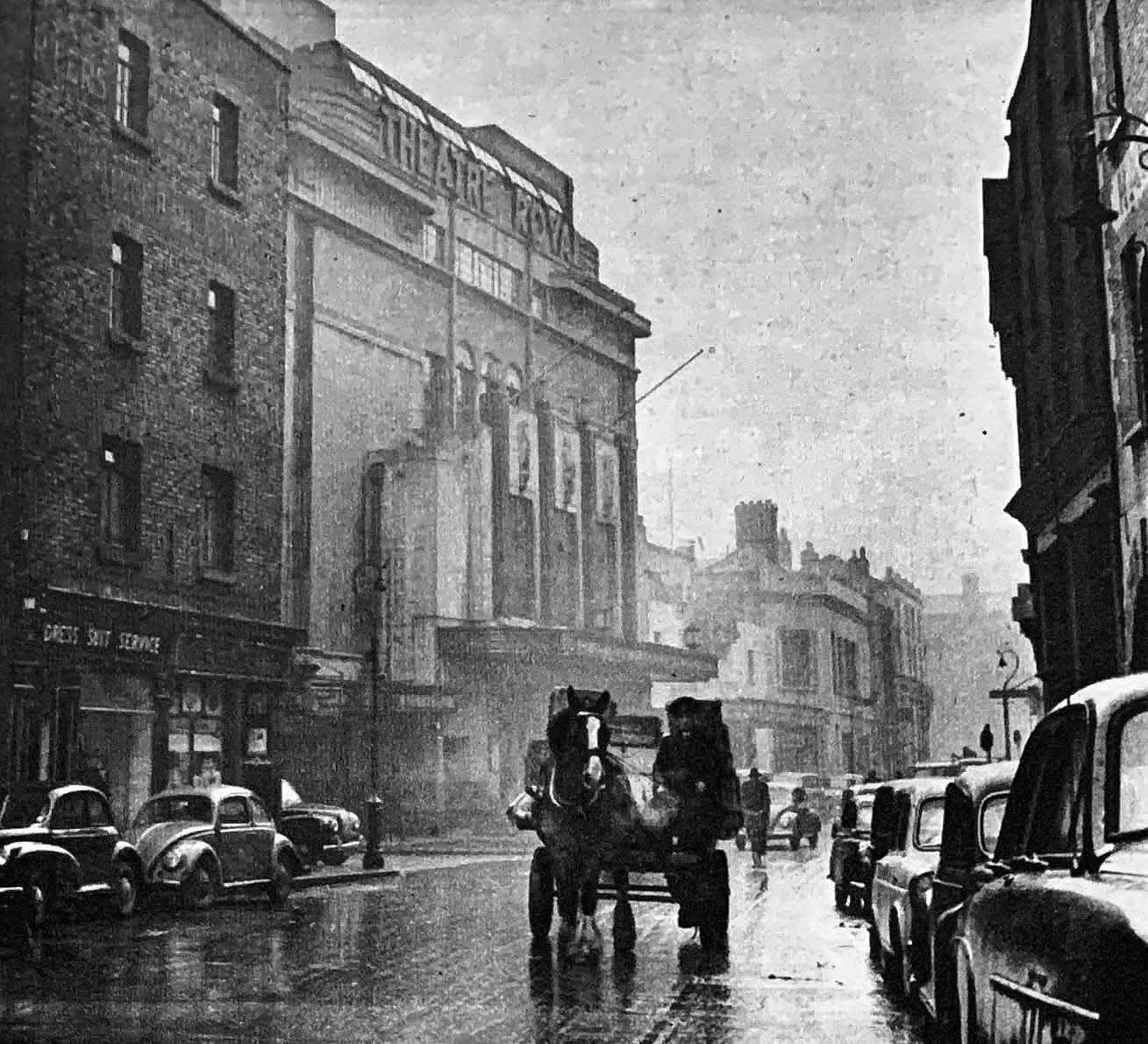

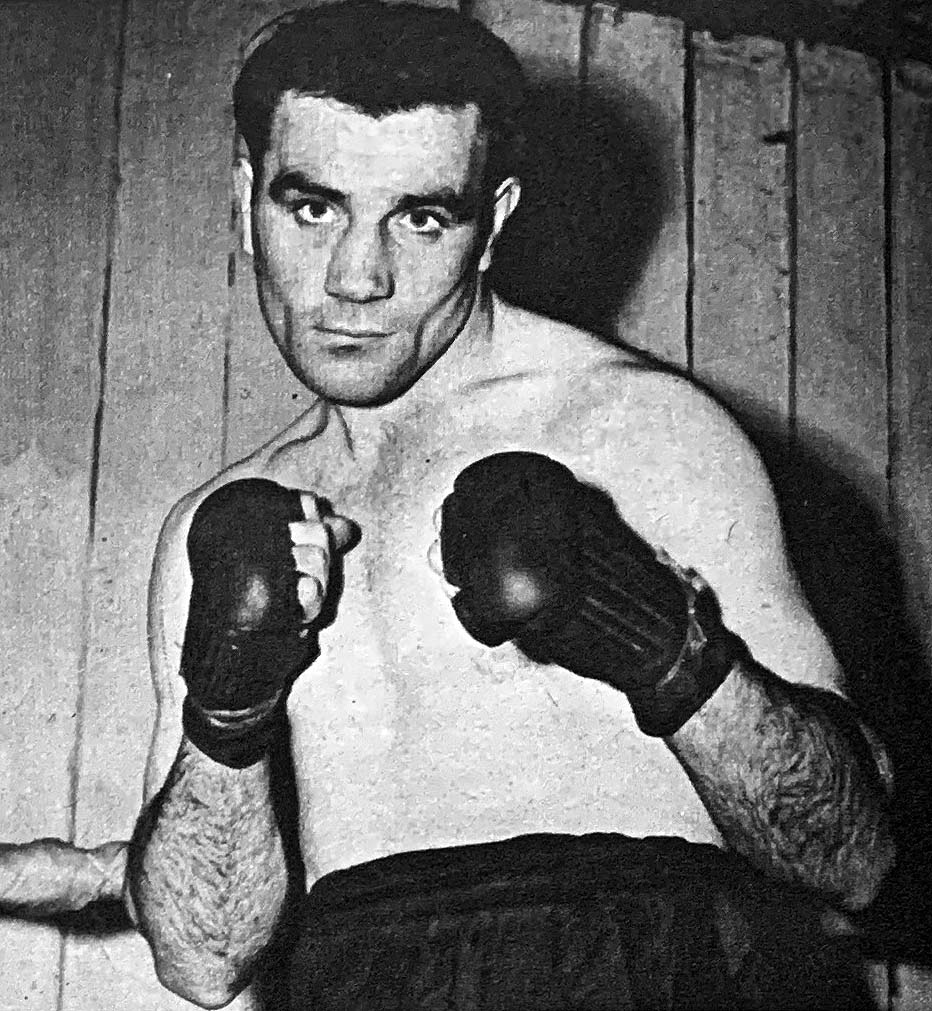

I should have known from the start that it would be one of those trouble-ridden broadcasts. Up until the day of the fights, it was not established that there would be a commentary at all on the Jack Solomons promotion at the Theatre Royal, Dublin, where British champion Bruce Woodcock was meeting Martin Thornton, a whale of an Irishman from Spiddal, in Galway – a Gaelic-speaking area in the west.

Using an argument he has often adopted since, Solomons objected to a broadcast on the grounds that he had between four and five thousand seats to fill and the commentary would affect the attendance. Everything depended on a meeting between Solomons and the director of broadcasting on the day of the fights. After this get-together, it was announced that there would be no broadcast, and I was downtown having lunch a little later when, over the café's radio, I heard the newsreader state that it was on, and that the fee was to be given to charity. This sounded to me as if Jack Solomons, whom I was to know well in the years to come, was showing just what he thought of broadcast fees.

What was more important to me at that moment, however, was to get to the weigh-in. I left my lunch in the middle of the main course and headed for the Theatre Royal. There I explained to Thornton, a compact, muscular ex-labourer discovered by English boxing manager Arthur Boggis, that as a gesture to the Gaelic-speaking area from which he came I proposed to do part of my commentary in the native tongue. Were there any names he would like me to mention? Thornton was excited by this idea, and as I was leaving he hailed me back and said quietly, "Now, Eamonn, when you're on the broadcast tell 'em I did my best."

This was before the fight.

It turned out to be dire. Completely outclassed, Thornton had no reply to Woodcock's heavy punching, and it was all over in three rounds. Instantly, there was a fantastic reaction as the crowd, disgusted at the uneven contest, booed, stamped their feet, shouted catcalls and threw a variety of objects including bottles. I had felt aggrieved that, due to the late decision about the broadcast, I had not been allocated a place at the ring-side. Now, watching this pandemonium from a box high over the stage, I felt distinctly relieved.

The quick finish left me with a lot of time on my tongue. I described the wild scene below, summed up what there had been of the fight and then, having exhausted the obvious material, talked about everything relevant and irrelevant. Eventually, I turned in desperation to the programme with its biographical notes about other boxers on that night's bill: but even this release was only temporary, for suddenly the hall lights went out. In the dark with nothing to see, very little to say, and a lot of time in which to say it, I rambled on about heaven only knows what.

When the lights came on again I had been talking in the blackout for a quarter of an hour.

I had done everything except whistle and sing, and it must have sounded appalling. Radio Eireann considered that it was a fair effort to overcome the difficulties, and commentaries came up more frequently. I was given another series, sharing a Friday afternoon cross-talk show with Louis Spiro, a sad-faced business man whose eyes always gave the impression that the joke was on you. It was a commercial programme in time hired out by Radio Eireann, and Spiro was owner and managing director of a dyeing and cleaning firm which sponsored the show. It was unforgivable, but we became Spotless and Stainless and some of the patter we used makes me blush now to think of it.

I was still feeling awkward about some pronunciations and the "u" sounds, which had bothered me so much in elocution class and on the stage, were still an embarrassment. One day, during my K and S show, I was so conscious of this that instead of saying "pure food products" I said "poor food products" - a slip that might be expected to have more severe consequences in a commercial plug than in a public service broadcasting programme. To my astonishment, nobody complained - not even the sponsors.

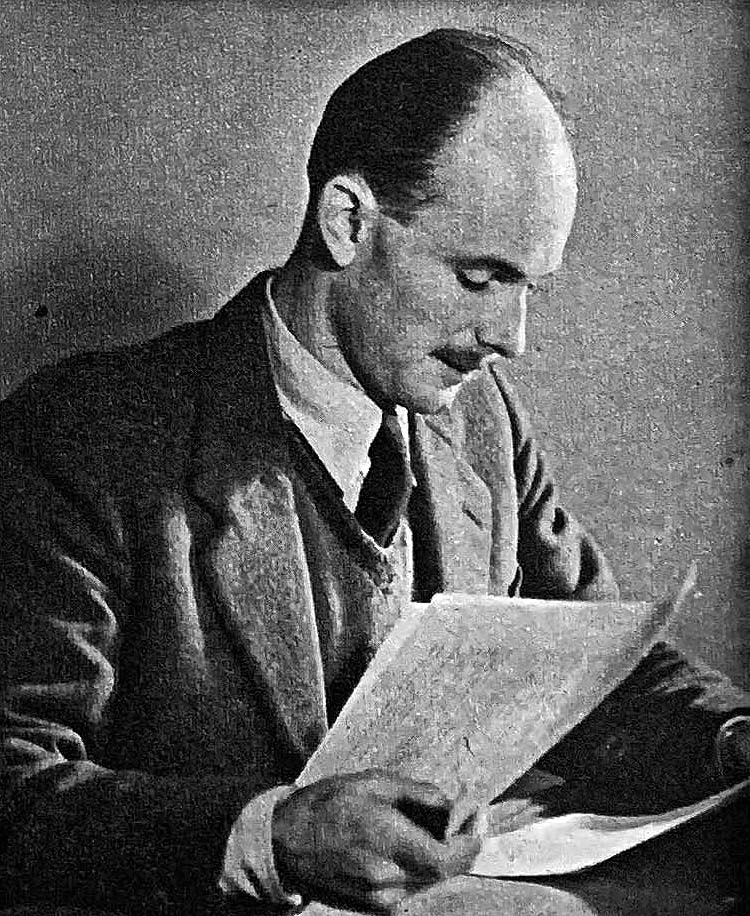

At this time, I was listening a lot to the BBC, and especially to a boxing commentator named Stewart MacPherson. His assurance, fast talk and novel turn of phrase intrigued me. As my admiration for MacPherson grew, so did my conviction that a job on the BBC was the aim of all broadcasters. I wrote to London introducing myself and asking about the prospects of doing some programmes there. The reply was a long way from being encouraging. I wrote regularly after that, and once packed several recordings of my commentaries off to the BBC.

Not surprisingly, for the corporation was well off for commentators, I encountered a massive indifference to whatever talents I thought I possessed. In Dublin I was too far away to be of much use, and the BBC saw no point in having me come across the Irish Sea for an audition.

This frustration apart, things were going better, and presently I was offered what I had wanted for some time, an interview programme. We called it Microphone Parade, and its nearest BBC equivalent would be In Town Tonight. All through the week I interviewed visitors to Dublin from all over the world, tying up the recordings into a complete Saturday night show.

I met Gene Tunney this way, Joe Baksi, Woodcock's conqueror, and Jack Train with whom, much later on, I was to work for the BBC. It was a fascinating programme to do, and full of novelty, but it also made plain to me that I had reached saturation with Radio Eireann. Once more I pelted the BBC with reminders and recordings of my work.

The talk of Dublin around this time was a quip-cracking quiz master named Eddie Byrne whose give-away show Double Or Nothing, was packing the Theatre Royal night after night. I had seen it two or three times as a member of the audience when, right out of the blue, I was invited to meet the theatre chiefs, who offered me a comparable job to Byrne's in their theatre in Limerick.

At £40 a week for the run it sounded fine; but there was the question of my radio shows. I agreed to the proposal on condition that I could keep my two sponsored programmes running - my second line of defence was still with me. As Limerick lies 123 miles south of Dublin, it seemed a difficult combination. Only with a car could I be sure of visiting Dublin on Thursdays and Fridays for my lunch-time radio commitments and getting back to Limerick the same nights for the stage shows.

I invested £75 in a battered and obsolete Morris 8 two-seater sports car and, the day before I was due to leave for Limerick, took my first driving lesson from a friend. After a couple of hours I dropped him off and drove to the National Stadium for a boxing commentary. Next night, an acquaintance hailing from Limerick joined me on the run and I welcomed his company, for as well as being a driver of some experience he was also a useful mechanic. I reckoned the chances of a breakdown were at least even.

It was a bitterly cold, damp night with the rain falling hard, and the car was like a colander. We must have done seventy miles before the engine wheezed, spluttered and died. My co-driver looked under the bonnet, shrugged helplessly, and said: "try the start. Let's hope she'll fire." There was no response, except that the starter knob came out farther than it should have done. Apart from an army camp down the road there was nothing for miles. We stuck up a couple of newspapers to keep out the draughts and settled down for the night...

The road from Dublin to Limerick is flat and featureless, but it had all the challenge of a Monte Carlo Rally for me and my car. Each week after the Wednesday night show in Limerick I would set out for Dublin, arriving home around four o'clock in the morning. There was time for only a few hours sleep before the broadcast.

I knew that sooner or later I would be in a jam, especially now that the ancient car was taking extra punishment because of the hectic social life I was leading in Limerick and its environs. Through the Double Or Nothing show, in which competitors from the audience answered questions for gifts and cash prizes, I made a number of friends, many of them from nearby Shannon Airport. It was a sort of clearing house for the Western world, and the practical side of the American drive in commercial aviation was everywhere in evidence. Huge US air transports were parked all over the place and, as well as aircrews, there were hundreds of British, Irish and American construction workers.

When the weekend weather was good, whole parties of us would drive off in a convoy of cars to Galway, and swim in the sea until well after nightfall. Back in Limerick we would keep the party going into the small hours in one of the bone-fide houses selling late drinks, or in a club to which we belonged. It was a breathlessly hectic existence, the sort that causes one to marvel in retrospect at one's endurance.

Fortunately for me, these wild excursions were mostly confined to the weekends, though my Wednesday and Thursday shuttling between Limerick and Dublin was almost as exacting. Tiring of the overnight journeys I cut the thing finer and took to driving to Dublin and back the same day. After the show one night, the theatre stage manager, a quiet little man, confided to me that he had never even seen Dublin. "Would you like to come up with me this Thursday?" I asked him.

Alex said he would, but that he intended to go fishing all day Wednesday night. I collected him on the Shannon Bridge at six o'clock in the morning, and somehow he got his rod and tackle into the back of the car.

In Dublin, I left him to look around while I recorded my disc programme. It was a gloriously sunny day, and on the return journey I pushed back the hood and prepared for a pleasant run. It was possible, after a little time, to run the car up to 55 m.p.h. and we were travelling at this speed as we approached Monasterevan.

I remembered too late the sharp bend leading into the village street: a wall loomed up, I put my foot on the brake pedal, and the tiny car skidded violently. It slewed round and the offside rear wheel hit the kerb with such a jolt that the door on my side broke off. I was flung into the dusty street, and I watched the rest of the incident in a sort of dazed slow-motion.

Alex, who had never driven in his life, snatched at the steering wheel and I saw with dread that the car was heading straight for the doorway of a house on the far side of the street. I expected it to crash straight into the front room, but Alex tugged the wheel just enough for the car to strike between the door jamb and the adjacent wall of a pub. A drainpipe clattered down in fragments. The other car door flew off and Alex sat there, looking crestfallen rather than damaged. I was bruised and filthy, but apparently I had broken no bones. I was already trying to pull the car off the wall when a big man in his shirtsleeves appeared in the house doorway.

I knew by his trousers that he was a policeman.

A humane man, he was more concerned about us than about the house and after ensuring that we were little the worse, he glanced at the broken stonework and shrugged, saying, "Ah well – what's the use?" By now, the village was coming to life. The local garage man had started to fix the car when the innkeeper appeared, worried about his drainpipe. He summoned a drainpipe expert, who assessed the damage instantly. "Thirty bob," he said.

I handed this over to the innkeeper.

Next, the garage man explained that if we drove slowly the rest of the way there was no reason why we shouldn't make Limerick.

"This is a miracle," I said. "How much?"

"Half a crown," he said.

Poor Alex was speechless, and doubtless already determined that never again would he leave his beloved Limerick.

The show had already started when we crawled into town, Alex was the first to enter the theatre carrying the front bumper, the radiator grille and other remnants and someone stopped him on the stairs and asked casually: "Oh, what's happened to Andrews? Is he killed?"

There was no time to change, or even to wash. I went onstage as I was, grimy and tattered, and told the audience what had happened.

I have driven to Limerick in more respectable cars and in happier circumstances, often since then. I always go through Monasterevan, and to this day that drainpipe has not been fixed.

My contacts in the American airline people at Shannon gave me an idea for my disc programme. It occurred to me that if I could only get freshly cut discs straight from the United States, I could give my show a boost and a reputation for topicality. The Americans like the suggestion and when the first batch of records was flown in from New York to Shannon, they assigned one of their pilots to fly me and the records on the last lap to Dublin, a publicity stunt that came off well.

The plane we used was a Flying Flea which was the personal property of the pilot, whom I knew as Tony. The trip took only two hours and afterwards I persuaded Tony to fly me to Dublin regularly for my Thursday and Friday programmes. We hedge-hopped most of the way at a 60-m.p.h. clip.

Early one morning, Tony telephoned to say that he would be unable to take me to Dublin that day as he had been assigned suddenly to a trans-Continental flight. "Sorry about this," he said. "It just can't be helped." At eleven o'clock that morning I had an interview to record with Wilfred Pickles, who was visiting Dublin, for the following Saturday's Microphone Parade. I explained this to Tony, and he offered to try and find another pilot willing to fly me. He was back on the line within ten minutes.

"Okay," he said. "There's a character here called Sam Pratt who'll take you. Meet him at the airport at eight o'clock." I decided to drive to Shannon and it was lucky that I set off early, for the car wouldn't start and I had to hitch-hike instead.

Sam turned out to be an elongated Texan with an elongated drawl and he didn't use two words where one would do.

We climbed aboard the Flea and were flying steadily over the fields at something between sixty and seventy miles an hour when Sam turned round in the open cockpit in front and hollered: "Smoke?"

Because Tony had always made an insistent point about no-smoking on account of the danger from the fuel fumes, I asked him to say it again.

"Smoke?" His voice came louder downwind.

"Yes," I said, still rather puzzled.

Suddenly, the tiny plane zoomed into a vertical dive. My stomach left me. We hopped a tall tree and a hedge, and then we were down rather uncomfortably in a cultivated field.

Sam climbed out and I followed.

"Okay," he said. "Have a Camel."

When we were aboard again, Sam exasperatedly discovered that we were short of fuel, and said that we could not possibly risk flying on. We took to the road, until we came to a filling station, where we bought several gallons of petrol in cans, enough to get us to Dublin.

I was already concerned about the delays, and felt more than slightly annoyed with Sam, but worse was to happen. Over Dublin Airport, Sam could not get landing permission. Without a radio, he circled tightly, waggling his wings without response. When finally we did get in, it was ten minutes past eleven and I knew someone else would already be doing the Pickles interview.

I made no further interview arrangements after this.

Double Or Nothing, which had originally begun on a five weeks' arrangement, was regularly extended. I kept up the suitcase existence, and had a radio set installed in my dressing-room to keep abreast of what was happening at Radio Eireann for the radio column I was writing for the Irish Independent.

After about five months in Limerick, however, I was invited to take over the same show at the Theatre Royal, Dublin. Eddie Byrne was moving out to go into films and other work.

I accepted at once, for it seemed a perfect arrangement: I was tiring not only of the constant journeyings but also of the high life at Shannon, which was also becoming too expensive for my peace of mind. In spite of my fairly good income, I was saving nothing.

For the Dublin audiences, Double Or Nothing was worked on a slightly different formula and included bigger prizes - the jackpot sometimes would be a motor-car, and Thursday was ladies' night. And instead of having people answering questions, I would often have them performing strange manoeuvres such as walking a straight line under all kinds of duress.

The pranksome students from the National University were the people we mostly had to watch: some of them saw easy money in the show, and tried to come up repeatedly. I had to send many a student off the stage after recognising a familiar face, though mostly they never got as far as that because of the vigilant commissionaires we employed.

One ladies' night, I found myself face to face with a slinky blonde who hipped her way over to the microphone and replied with some indignation when I suggested I had seen her before. It seemed that I had muffed this one: I wasn't sure about it, and I just had to take her word.

When it came to the gimmick in which I asked her to sing, she said she could not do so because she had a heavy cold. She kept harping on this cold, and I didn't know why. For the jackpot, she was one of three women who had to walk a slippery pole and she made it so easily I marvelled at her confidence and athletic prowess.

Months later, at a dance in a hall run by a friend of mine named Lorcan Bourke, a girl came up to me and mentioned that her student brother had twice won prizes on my show, once when he dressed as a woman...

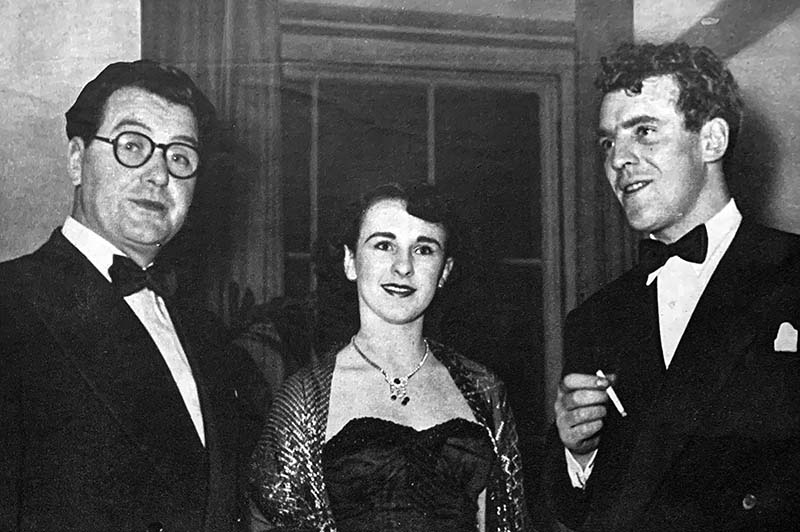

Lorcan. A fresh-complexioned man with black curly hair, was in the bar of the Theatre Royal after one of my Double Or Nothing shows and beckoned me over for a drink when I walked in. He introduced me to his wife and his daughter, who was as dark as Lorcan and with eyes full of gaiety and mischief. Her name was Grainne, and we were soon getting on so well that I suggested seeing her home. It was pouring down outside, and the car had leaks as well as draughts, and I hoped she wouldn't mind very much. I switched on the ignition - and then remembered that I was out of petrol. I was also out of ready cash. I turned to Grainne and said awkwardly: "Can you lend me ten bob for some petrol?"

It was an old-fashioned look I got, but she handed me the money from her handbag. After leaving Grainne, I wondered all the way home what she must have thought of a man who offers to drive her home and then asks for the petrol money. Nevertheless, we took to meeting occasionally; for my part, it would have been oftener but for the amount of work I was now doing. The Dublin job had put me right back in circulation with Radio Eireann, and only if there had been eight days in a week could I have done any more.

Again, I wrote to the BBC, this time to S J de Lotbiniere, Head of Outside Broadcasts, asking about the possibility of doing some sports commentaries. I enclosed one or two recordings. By return, I received a politely clinical letter explaining that my voice was not exactly right and repeating that it would not be possible to bring me all the way from Ireland for a test.

For a time, despite the Double Or Nothing run and all the work I was getting from Radio Eireann, I felt acutely frustrated as further letters to other BBC departments failed to produce any worthwhile results. My mother and father were somewhat put out that I should even contemplate leaving Ireland; yet, much as I loved the country, I felt that I had reached an impasse in Dublin. The BBC offered a bigger potential future.

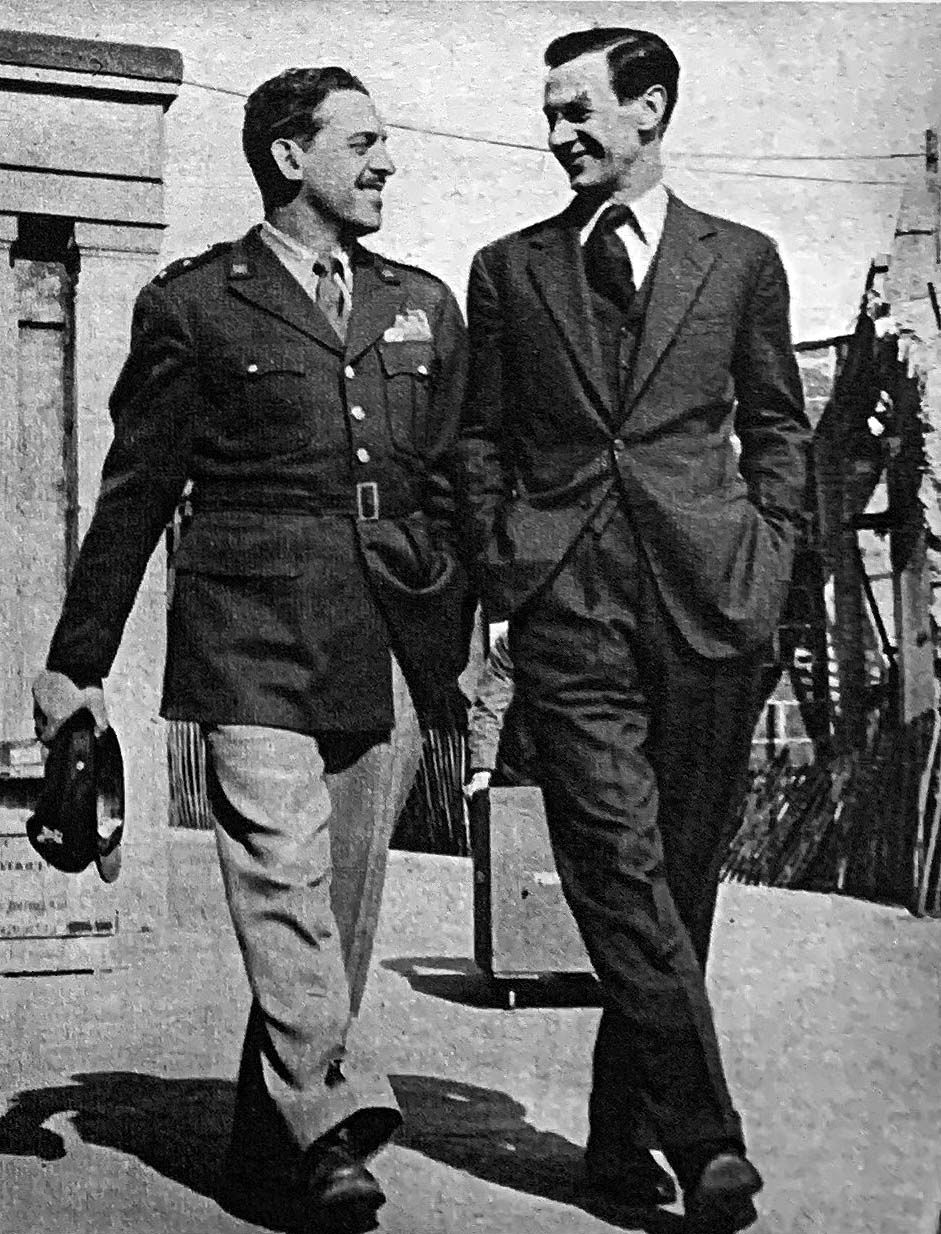

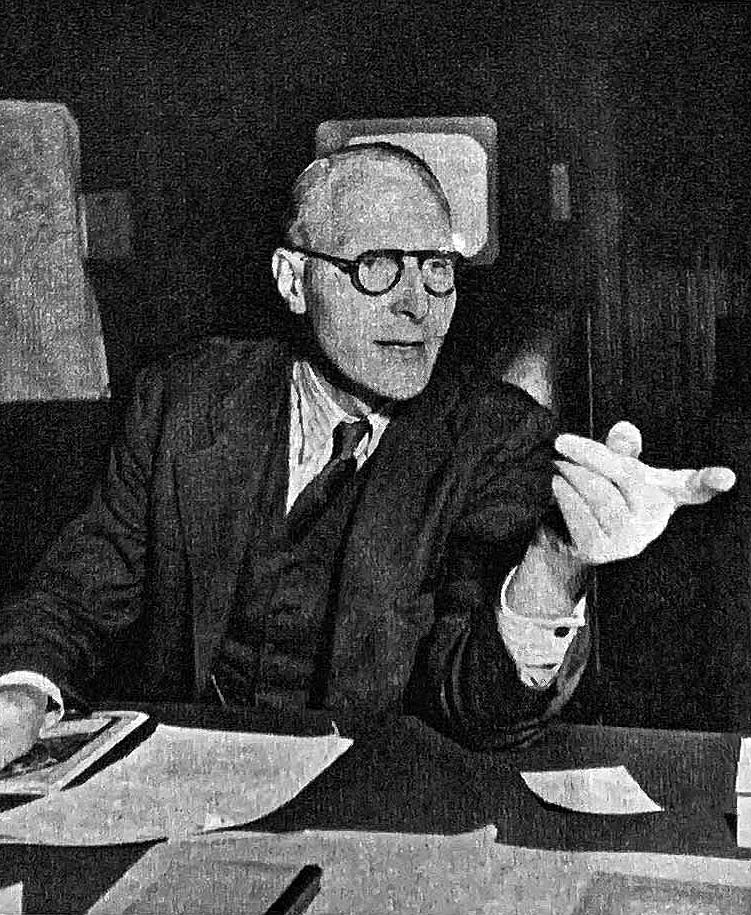

Then, quite unexpectedly, two things happened which changed the picture completely for me. For one of my Saturday night Microphone Parade programmes, I interviewed the man who was then Controller of the BBC Light Programme, Tom Chalmers. He hinted that I might find some encouragement if I were in London. This was only a glimmer of hope, but it dispelled my growing feeling that the BBC would not be interested in me whether I was in Tottenham or Tipperary.

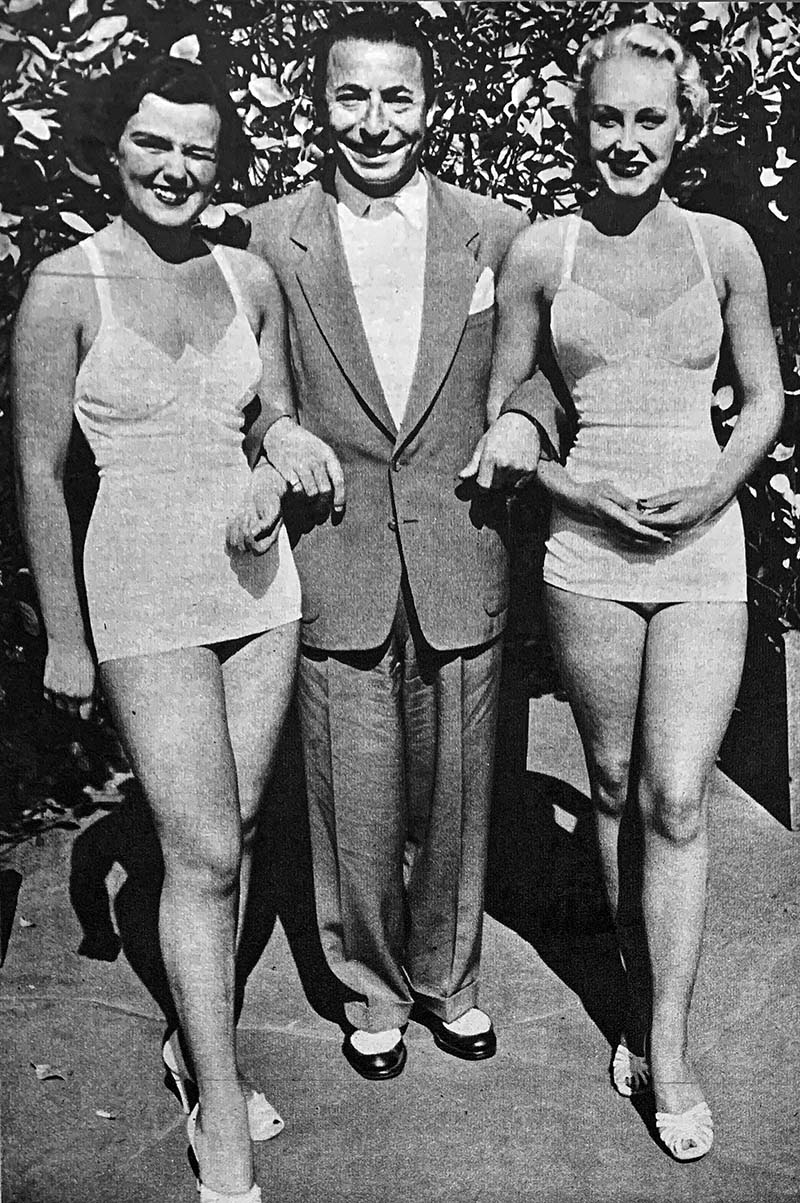

The other significant thing was the arrival at the Theatre Royal of Joe Loss, the sleek-haired and amiable business man and band leader, with whom I got on well right from the start. Joe said he enjoyed my Double Or Nothing spot and that he would like to take me with the band on a music-hall tour of England. It looked like the break I had been seeking. It meant that I could really serenade those BBC producers on their own doorstep, and perhaps, with luck, build a reputation like Stewart MacPherson's.

Some of the people I respected most considered it was too big a risk, for it would mean cutting away from everything that had taken me almost nine years to build. I saw it rather differently. Failure would mean a quiet return and picking up the old threads again - but what would my friends think, and the family, and Grainne? I had to make a success of it. I packed a hold-all and flew to London.