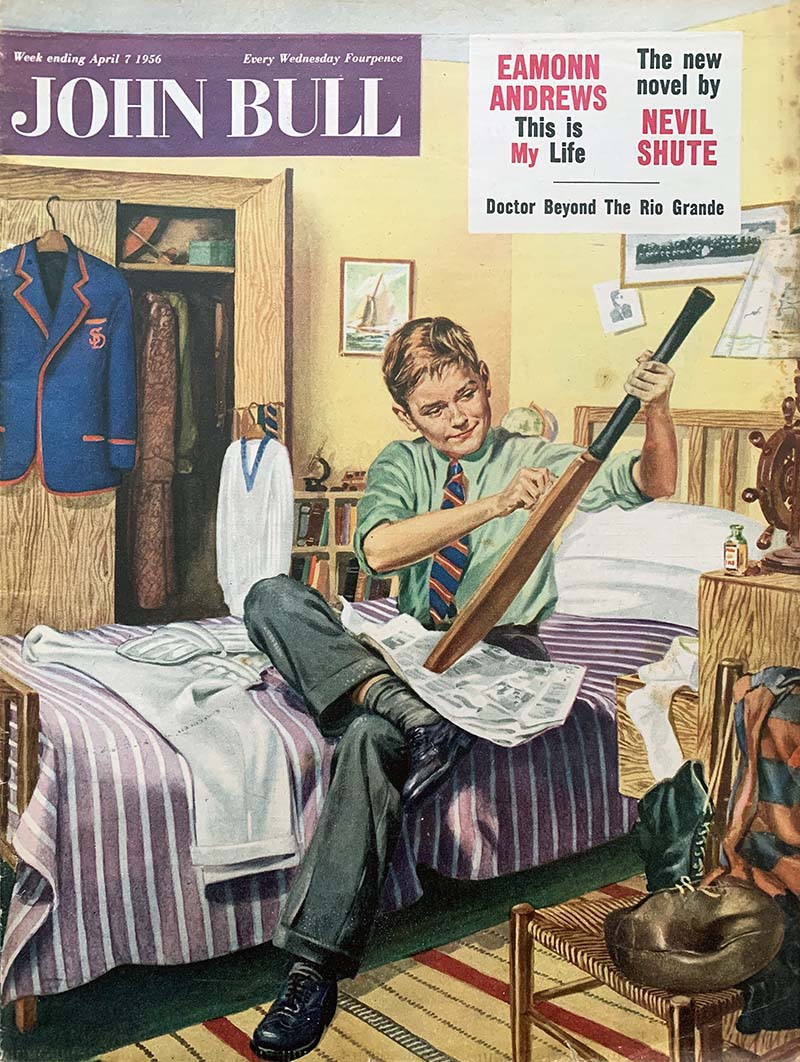

Big Red Book

Celebrating television's This Is Your Life

7 April 1956

a brief biography

The Legend That Was Eamonn Andrews

a celebration to mark the presenter's centenary year

first-hand recollections

Triumph - at £6 a week

by EAMONN ANDREWS as told to Wilfred Greatorex

For weeks I starred on the BBC... and then became a forgotten man. Now I had a second chance - in what seemed to be a madhouse

If I had set out on my first visit to London with somewhat grandiose expectations I now felt, after almost a fortnight in the most exciting city on earth, more like a candidate for the Lonely Hearts Club. The heart of show business beat coldly. Each morning and afternoon I sought out producers in every BBC department from outside broadcasts to variety and recorded programmes.

I found the corporation's reception desks harder to pass than the policeman at the House of Parliament, and when I called to see Tom Chalmers, then Controller of the Light Programme, whom I had interviewed on Radio Eireann, I failed to get beyond the beribboned commissionaire at Broadcasting House. This great off-white building, which had filled me with awe at first sight, took on an even more forbidding grandeur.

It was 1949, and after building some sort of reputation as a sports commentator, quizmaster and disc jockey in Ireland, I had come to London to start a music-hall tour for bandleader Joe Loss with my give-away quiz, Double Or Nothing. I saw it as the opportunity I had long wanted to break into the BBC, but so far nobody was in the least impressed by my voice or my persistence. After each night's performance at the Shepherd's Bush Empire I resolved to intensify my search the following morning, and one day I did get in to see S J de Lotbiniere, Head of Outside Broadcasts.

He put one of my Radio Eireann boxing commentary records on the turntable in his office, listened closely and then, straightening up his full six foot six inches, explained that I had a lot to learn. To my intense discomfort, "Lobby" then put on recordings of Raymond Glendenning and Stewart MacPherson to illustrate the mistakes that he said I was making. It was all so clinical that I left with the kind of feeling one gets after a diagnostic session with the doctor.

I badly wanted to stay in England. The possibility that after the Double Or Nothing run I might have to return to Dublin, tail down, to pick up the old threads, filled me with misgivings; any sort of work with the BBC would be better than that. Only a few days remained to fix something: soon the Joe Loss Show, and me with it, would be in the provinces far from the centre of broadcasting. It was then that I was seized with the notion that if the BBC didn't want me, the film studios might.

At this time an Irish actor called Kieron Moore, for whom I am often mistaken, was at the top. Imitatively, I called on his agent and appointments were made for me at Pinewood, Ealing and other studios in the London area.

I felt as provincial as a dalesman and as Irish as potatoes and, like most young men seeking a professional break, I was anxious to please; so anxious that I was ignored. A few casting directors interviewed me, but many a time I would be left hanging around the studios praying that someone would notice me. I remember one occasion when I loitered about the set like the invisible man himself while a few feet were shot of a film called Another Shore, I was on another shore all right. What I did not appreciate at the time was that London was over populated with under-employed Irish actors.

This wintry reception was tempered somewhat by the extreme friendliness of the boys in the Loss band, and my sense of loneliness by some of the competitors who came up for the Double Or Nothing quiz. One night, among four volunteers from the audience, appeared a little man with a subdued manner and a nicely controlled voice who answered my first question correctly for five shillings and then identified a tune.

"Would you like to sing a bit of it?" I asked.

The band struck up, and this man's voice was great. "No more questions for you," I said, impressed. "Here's your quid."

Today, Robert Earl is a recording star.

He was not the only competitor with ideas about breaking into the jungle of show business, and it all helped to give me the feeling that I was part of a big, happy family - a big one, anyway. At least, I was not hunting alone.

After paying my fare, I had reached London with £20. The Joe Loss job was bringing in £40 a week, part of which I posted home in case it was needed there. My father had been ailing for some time, and I still had pangs of remorse about leaving home at such a time. The rest of my salary was frittered away. There are few more dangerous occupations than touring the provincial music halls, for one is left with so much time on one's hands and the temptations to waste it are almost unavoidable.

As I remember it, this tour from my point of view was a procession of visits to the cinema, parties, and three memorable visits to dog tracks. I have never been able to resist a tip, and as one of the Loss bandsmen knew the dogs as well as his band scores and had a cast-iron system, the bookmakers took more than a reasonable share of my earnings. I have never been able to look a dog straight in the face since.

When the tour ended, I had saved not a penny. I took up where I had left off in my search for BBC engagements or a part in a film, and I was offered a minor role in a play. The duration of rehearsals, however, would have put too great a strain on my reduced finances, and I began to think again of going back to Dublin. I was finally convinced when I heard Stewart MacPherson doing a brilliant boxing commentary: it would be better to keep myself occupied in Dublin than idle in London. Fortunately, I had enough money for the fare home.

The greatest compensation now was a personal one; I was able to see Grainne, the lovely dark-haired girl to whom I had been introduced by her father. The work also began to roll in: boxing and international soccer commentaries, and a Friday programme for Radio Eireann shared with another broadcaster, Gus Ingoldsby, called Sports Stadium. Nevertheless, I was terribly upset and frustrated. I kept up my letters to the BBC, and twice there were alarms when I heard that Stewart MacPherson was leaving to work on the other side of the Atlantic. They were only rumours.

In the event, it was almost by coincidence that I made my first really worthwhile contact with the BBC. Radio Eireann decided to fly me to London to record interviews for Sports Stadium with the London fly-weigh boxer Terry Allen, who was due to fight Rinty Monaghan, and the American Joey Maxim, whose fight was pending with Freddie Mills. For this job, the BBC was helping out with facilities, and I little knew when I was introduced to the Head of BBC Recorded Programmes that he would play such a considerable part in shaping my future. Brian George went out of his way to be helpful. He first put me in touch with Maxim's manager, a sharp-mannered livewire named "Doc" Kearns.

"Sure you can interview Joey," said Kearns. "Best time is at breakfast. Be at the Lex Restaurant and Joey'll say something."

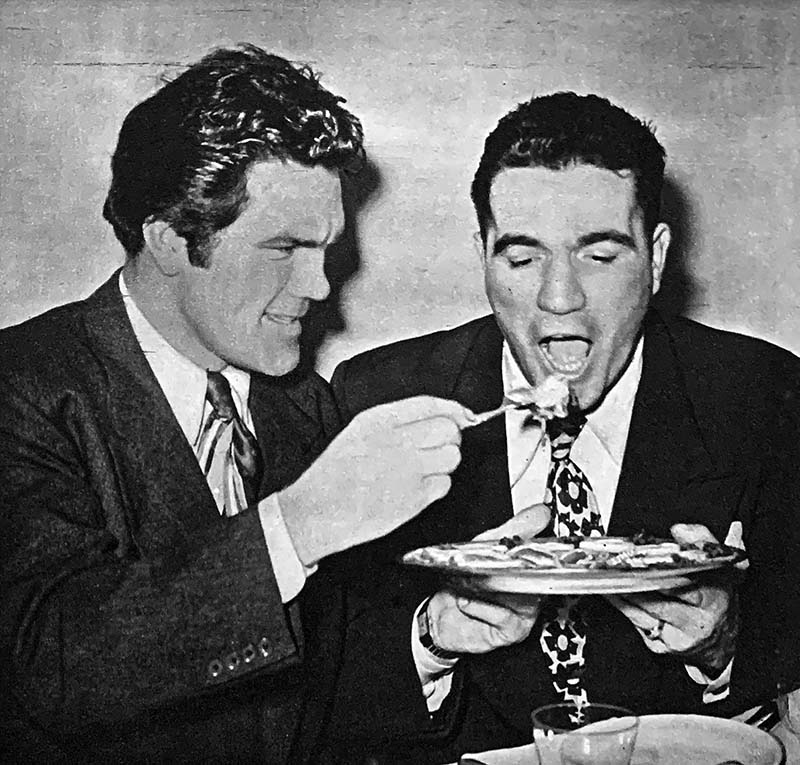

When we arrived with the BBC recording van, Joey was laying into half-a-dozen eggs and several rashers of bacon as if he were hungry. Momentarily at a loss, I asked if he always ate like this during training.

"Gee, no!" Joey replied. "I've an appetite like a bird." He winked at Kearns and added: "A vulture!"

With two interviews in the can, I mentioned to Brian my admiration for MacPherson's work and he asked if I would like to meet him. At lunchtime, he introduced us over a beer in a pub near Broadcasting House, and it was like shaking hands with one of my ambitions. MacPherson readily agreed when I suggested a recorded interview with him for Sports Stadium, and back at Broadcasting House he rasped back answers to my questions. There was as much thrill for me in doing an interview on BBC premises as there was in meeting MacPherson. The trip had paid off handsomely: in an oblique sort of way I had got beyond the BBC barrier.

Not long after this I heard that MacPherson was leaving for Canada, and this time it was true. Hopefully, I saw myself as his successor on boxing commentaries, but it was his other line, the chairmanship of Ignorance is Bliss, the crazy uninhibited panel show, which created the first opening. Without optimism, and half-expecting another brush-off, I applied for an audition. I was invited to attend, and it turned out that there were five other potential chairmen, including Jack Jackson, Joe Linnane, and a walrus-moustached gentleman oozing charm and good manners, named Gilbert Harding.

In a BBC studio, each of us was given part of an Ignorance is Bliss script to read before a small audience composed mainly of corporation staff. It was impressed upon us by the producer that it was of some considerable importance that we should be rude to Gladys Hay, a matronly comedienne who was just as good-humoured off the air as she was during broadcasts. This worried me a little, yet I was oddly more concerned about the way the charming, highly-cultured English gentleman would react to this requirement. I kept thinking that he could not possibly be rude to anyone. It was years before I was disabused of this idea.

I returned to Dublin not knowing who had been selected, and I was astonished some three weeks later to learn that I would preside over the first six programmes of the new series. Plainly, the BBC was taking no chances – and, for that matter, I wasn't either. With the programme scheduled for Monday nights, I planned to keep my Radio Eireann commitments alive by flying from Dublin on Sundays and returning on Tuesday mornings.

While I was in Dublin after one of these trips my father took a turn for the worse in his illness and on the Saturday he died. Such are the demands of the career I had set myself on that I had to take a plane back to London after the funeral on Monday to appear in Ignorance is Bliss. It was one of the blackest days of my life and I was relieved to get the show over.

This was one of the times when I preferred to be alone; at others I would have given anything for company. I missed the friends I had made in Dublin, and I appreciated the thoughtfulness of Brian George, who, besides introducing me to other BBC people, often saved me a solitary weekend by inviting me to his delightful home at Sonning-on-Thames.

It was when we were preparing to take Ignorance is Bliss on a music-hall tour that I met another man who was to influence my future more than anyone. Back in Ireland, people had warned me about the pitfalls of London, and I thought I knew all of them until Edward Sommerfield indicated others that I had never imagined.

A stickily built business man who always smoked cigarettes through a holder, he had just returned to London after tiring of inactivity on the Riviera, where he had gone to live. He understood better than anyone what I wanted to do, warned me of the passing nature of my line in show business, and urged me to broaden my scope. He made me feel my rawness.

While I was on tour, Teddy kept up the approaches to the BBC on my behalf and, though we had little or nothing to show for it, I did have the feeling that I was no longer entirely on my own. As a stage show, Ignorance is Bliss, was no world-beater. There were a few encouraging weeks, notably in Dublin, where we had a riotous time. I certainly had fun showing Harold Berens some of my favourite spots. I enjoyed it, too, for the company of Gladys Hay and her husband Al Potter, with whom I usually shared "digs". Gladys, a fair player herself, introduced me to golf, and as a morale-builder was indispensable, for the show itself was going some way to prove that a top radio series doesn't necessarily convert into a successful music hall show. Our Tuesday night show at the Wood Green Empire coincided with a big fight broadcast, and the theatre was like an echoing desert.

We appeared at the Chiswick Empire during the Wimbledon fortnight, and one of the competing players, an Irishman called Murphy, offered to get me a player's ticket. On the morning of my intended visit to Wimbledon, however, Grainne turned up unexpectedly in London after a holiday to Spain. When I rang Murphy to explain, he said: "Okay. Bring her along. We'll meet at the main gate and see what we can do."

Centre Court seats were as hard to come by as BBC engagements, and Murphy asked if I would be willing to try a bluff.

I agreed, and so did Grainne. Murphy had two lapel tickets attached to blue string. He handed one ticket to Grainne, kept the other himself, and gave me the string from his ticket. Grainne led, I followed, and Murphy brought up the rear. The gateman saw Grainne's ticket, caught sight of my blue string, and the auto-suggestive stratagem worked. We took seats in the competitors' section.

My life was so barren socially at this stage that Grainne's arrival and the outing must have gone to my head. I decided to demonstrate my worldliness and my improving professional position by taking a party to a night club for dinner. I had never even seen inside one of these places, let alone entertained guests there. As well as Grainne, I invited Murphy and another friend named Ken Riddington, and their girl friends.

Suddenly, I was overcome by the realisation of what I was leading myself into and, thinking that Teddy was worldly-wise enough to get me out of any scrapes that might arise with the waiters, I added him and his wife Dorise to the party. All through the evening I was vaguely uncomfortable, feeling sure that I would mix up the ordering, or make a faux pas with the staff by undertipping or overtipping. When the bill arrived, I was incredulous. I have never attended a night club since as a client.

Although I did not mention it, the thought of marriage occurred to me for the very first time during this visit of Grainne's. I was not really sure about her feelings, and I wondered if she regarded me as just another of those confirmed Irish bachelors who instinctively go into slow motion whenever matrimony looms up. In fact, I never have considered this characteristic to be the Irishman's credit: next to the Great Famine of more than a hundred years ago, it is the main reason for the under-population from which Ireland suffers. Nevertheless, now was no time to be considering marriage. I first had to get my prospects on a surer footing.

My experiences with the stage version of Ignorance is Bliss had only served to sharpen my caution. We had to take a cut in pay, and in Leicester business was abysmal. In the town's other theatre a farce in which a fellow-Irishman, Dermot Walsh, had a part was also taking a caning. When I went to a matinee performance, there were only four or five rows of people. In the dressing-room afterwards I felt sorry for Dermot and his fellow-players, who included Brian Rix and Wally Patch. I might as well have saved my sympathy, for the play was Reluctant Heroes, later to become as much a part of the London scene as the Tower of London. At the time, though, it made me think seriously about the gamble of show business.

I was more than ever ready to listen to Teddy Sommerfield's advice when I got back to London at the end of the run. He had fixed a number of BBC auditions and instructions for me, and as I was leaving his flat, he said: "There's one thing I've got to say. Remember you're not in Ireland any more. You're in London. You're in business. You must be on time for appointments. Don't give us this Irish habit of turning up two hours late."

The last remark infuriated me, but I meekly concurred. All the way back to my room in Bayswater I reflected on the words, and boiled up inwardly because unpunctuality had never been one of my failings. Of course, it was well-meant advice, and without Teddy's drive and shrewdness I would doubtless have returned to Ireland for good long before the tide began to flow. Come to think of it, the same Teddy has yet to be on time for an appointment with me.

For a long time, things went very badly. Not a single engagement came up for weeks, even though I was prepared to take on anything the BBC would offer, and when I was given a short story reading for seven guineas it seemed like success. I continued to live on what I had managed to save from the Ignorance is Bliss tour, and when the opportunity came to commentate on the Irish Cup Final at Cork one Sunday for Radio Eireann I leaped at it. The match was drawn, which meant I would also have to be back in Ireland the following Wednesday for the replay.

On the Tuesday night I had another story reading for the BBC, which I dared not sacrifice, so I arranged to catch an early morning flight to Dublin until I realised that this would not leave me enough time to cover the 166 miles from the capital to Cork. The only possible way was to catch a Pan-American plane that was stopping at London and Shannon, which would leave me only a seventy-mile drive in Ireland.

I had to be at Victoria at 6.30am. Leaving myself with half an hour to get from my "digs." I set out hoping to hail a taxi; but there was none in sight. With the seconds ticking away, I halted a noisy, broken-down lorry that would never have survived an efficiency test, and offered the driver ten shillings to take me to Victoria quickly. The lorry seemed to have no brakes, and I was sweating in sheer terror all the way. At Victoria, an airline clerk said that, because I had left no telephone number, he had been unable to inform me that the flight was held up for twenty-four hours.

Desperately, I tried to phone Air Lingus, but no one was on duty, and eventually I hired a car to rush me to Northolt in the slight hope that a passenger would have cancelled his seat on the Dublin flight. Luckily, one had: I wired Radio Eireann to find a driver named Joe whom I knew to be the only man in Ireland capable of getting me from Dublin to Cork in time for the kick-off.

Joe was there with his powerful Dodge when I landed. He drove with all the combined qualities of Stirling Moss and Sheila van Damm, and we were making fair time and had got within sixty miles of Cork when there was an almighty explosion as a back tyre burst, and the car careered wildly. Luckily, there was no one else on that country road. I was silent more with panic at the possibility of being late for the commentary than with fear.

Joe leaped out. "Now don't worry, Eamonn," he said. "Don't worry. I'll have this changed in four minutes. Time me if you like." He took precisely four minutes to put on the new wheel.

There were three minutes to the broadcast when I picked up the microphone in the commentary box. "Give me a test," the engineer said. I was so excited that in picking up the microphone I missed my grip and it dropped and broke. We got a replacement just in time...

Back in London, I continued to see producers in pubs, coffee houses and their offices, and never a thing did I get as a result. Ken Riddington had offered to let me share his room in his mother's guest house in Bayswater. I was asked nothing for lodgings, but chipped in with the food. When it came my turn, I went into Queensway, to the shops and market stalls, and bought tinned meat, onions, cheese, milk, radishes, a head of lettuce and sometimes celery – and mounds of potatoes.

In the tiny kitchen, I would make a pot of stew, and usually there was enough to last ten days. I ate some every night, though as time went on it became rather soggy and finally had the texture of sodden cardboard. Whenever it showed signs of losing some of its taste, I topped it up with fresh potatoes and carrots to give it a lift.

By now my total resources, including the clothes I stood up in, were probably not more than £20. There were days when I would walk the two and a half miles to Broadcasting House to save the bus fare, and in making telephone calls from my "digs" I would make a note in my diary to pay the twopences at the weekend in case the little money I had should be needed for an urgent appointment with a producer before then. Yet always the answer was the same: "Sorry I can't use you in my programmes for the moment, but I'll probably get in touch with you."

All through this bitter winter of my life, I was busy giving displays of nonchalance, hints of hidden wealth and now and then took the line, as a defence when all seemed lost anyway of I-don't-know-if-I-can-fit-it-in. These, the surest signs of an out-of-work actor, of the show business character who hasn't a single engagement between him and his Maker, probably deceived no one, least of all a sharp-eyed Scot named Angus Mackay.

Angus, editor of the BBC's Sports Report, was the first ray of warmth for a long time, but with a pauper's pride I was ready to put up the defence when we were introduced by Brian George in a pub close to Broadcasting House. It transpired that Angus, hearing me some months earlier on Ignorance is Bliss, had wondered whether my voice might be useful for his programmes; but, in the way these things happen, he had forgotten all about me until he had spotted me with Brian one day. He had asked if I was the big Irishman from Ignorance is Bliss, and suggested a meeting.

I was ready now for the usual producer's get-out, but Angus concluded our talk by saying, "Come along on Saturday and see how we do it. If you think you can manage it, I'll give you one of my programmes to compere." In addition to Sports Report, he also had Sports Parade and the General Overseas Service feature called Sports Review.

It was like hearing Gabriel's trumpet call.

I watched through a glass panel in the studio as the assembled sportsmen analysed and dissected that day's sport, and I felt inescapably as if I were in a lunatic asylum. Cutting across the four broadcasters' conversation was a persistent, unidentified noise. Angus made frantic signals through the glass panel, but no one paid any attention. He peered at each speaker in turn, then whipped suddenly through the studio door and began crawling across the floor on hands and knees like a dog searching for scraps. Somebody was tapping the discussion table with his knee. Angus located the offending leg, gripped the ankle and pinned it to the floor. It was plain to see whose leg he held from the expression of alarm that crossed one speaker's face.

"Well," said Angus after the broadcast, "do you think you can do it?"

"Yes," I said, "providing I may wear shinguards."

The next Saturday, November 25, 1950, I compered Sports Review for listeners in Australia, New Zealand, South America and other faraway places.

"Can you do Sports Report on the Light Programme on December 9?" Angus asked.

At last, I was in; soon, I was taking turns with Raymond Glendenning on Saturdays as compere of Sports Report. I was still earning only twelve guineas a fortnight, but the stew did not have to last quite so long any more.

One Saturday, with a football commentary to do from Chelsea, I worked it out that there was just time to get back to Broadcasting House after the game for Sports Report. At Stamford Bridge, the commentary box stands about forty or fifty feet off the ground, and access is gained by means of a ladder lowered by a pulley system. The ground was almost empty when we wound up the commentary, and I made to descend, but the man responsible for the ladder had hoisted it and left. I shouted to draw someone's attention, but for some minutes there was no response. Finally, I managed to instruct a late-departing spectator to lower it for me, and after a hectic drive through London I reached the studio just as John Webster was about to go on air with the football results. From that day to this, I have never attempted a Saturday afternoon commentary.

The New Year of 1951 dawned well for me: I had a mid-morning short story reading on the Light Programme, soon to be followed by my first television engagement - in the role I imagined myself best equipped to deal with, that of boxing commentator. I had to fight down my instinct to talk fast and describe everything, and I had to discipline myself to listen to producer Barry Edgar's instructions over the headphones without replying.

The work continued to build up, with cycle speedway and six-day cycle race commentaries - the latter a marathon for me as well as for the riders at Wembley - and a few programmes which later were to become a regular Sunday series called Welcome Stranger, in which I interviewed visitors to London for the Festival of Britain.

In April, I averaged twelve guineas a week and accepted an offer to do a commentary on a chess match. It was a rather extravagant affair, played between Professor Joad and a London bus driver, on the Festival site on the south bank of the Thames. The chessmen were schoolboys dressed up.

I had never played chess in my life. I found someone who understood it, bought half a dozen text books, and crammed like a student. Shallow knowledge of a subject is the worst failing of which a commentator can be guilty, and it was a great relief when it was all over.

This increased activity brought with it an unexpected embarrassment. Critics and acquaintances almost invariably had the same thing to say in print and when I meet them - that I was worse or better than Stewart MacPherson. It became painfully clear that I had become a sort of first reserve to a legend and, through no fault of his, the fast-talking Canadian was now an ogre in my life.

I was worried by these constant comparisons. I preferred to be told whether I was good or bad. This MacPherson business was still on my mind when I went over to Ireland for a few days' holiday in mid-year. Brian George had now assured me that Welcome Stranger was to be a regular Sunday series and, the comparison snag apart, things had never been better. On leaving to catch my plane, I told Teddy Sommerfield: "It's going too well. We're in for a smack in the teeth any day now."

After the London scramble, it was pleasant to slip back among old friends and familiar haunts - and, more than anything, to see Grainne again. While visiting Radio Eireann, the thought struck me that I might be happier there than chasing rainbows in London; but it was only a passing idea. In any case, others had taken over my radio work, and my brother Noel had stepped into my shoes as boxing commentator.

On the third morning, my mother called upstairs to say there was a telegram for me. It was from Teddy:

HOUSEWIVES' CHOICE ONE WEEK. GREAT CHANCE. WHOSE GETTING THE KICK IN THE TEETH NOW?

I could hardly believe it. I read the telegram to my sister Peggy, and she nearly swallowed her ear-rings. I was almost tempted to see this as the signal that meant I could safely propose to Grainne, but I was still not certain that my prospects were secure.

There was nothing to suggest that so much was going to happen in the seven months that were left of 1951, when my life was to be radically changed.