Big Red Book

Celebrating television's This Is Your Life

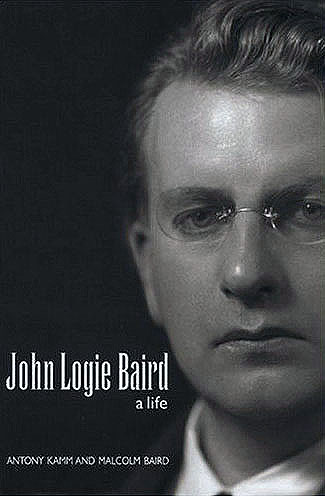

John Logie BAIRD (1888-1946)

- The only edition to feature a deceased subject

THIS IS YOUR LIFE - John Logie Baird, engineer and inventor, was honoured by Eamonn Andrews at the BBC Television Theatre.

In the only edition of This Is Your Life to honour a deceased subject, Eamonn Andrews paid tribute to the Scottish inventor, hailed as 'the father of all television', ahead of the forthcoming 21st anniversary of the world's first regular television service, which was launched on 2 November 1936 from Alexandra Palace in London.

Friends and colleagues gather to tell the story of how the Helensburgh-born engineer and inventor demonstrated the world's first live working television system on 26 January 1926 and went on to develop the first colour transmission in 1928, and in the same year, make the world's first transatlantic television transmission from London to New York, broadcast the first drama shown on UK television - The Man with the Flower in His Mouth - on the BBC in July 1930 and transmit the first live outside broadcast with the televising of The Derby in 1931.

programme details...

- Edition No: 39

- Subject No: 39

- Broadcast live: Mon 28 Oct 1957

- Broadcast time: 7.30-8.00pm

- Venue: BBC Television Theatre

- Series: 3

- Edition: 5

on the guest list...

- H J Barton-Chapple

- W C Keay

- William Fox

- William Taynton

- Ben Clapp

- Lance Sieveking

- D R Campbell

- Sydney Moseley

- Patrick Barr

- Margaret - widow

production team...

- Researchers: Nigel Ward, George Bruce, Michael Friend

- Writer: Peter Moore

- Director: unknown

- Producer: T Leslie Jackson

Friends and colleagues pay tribute to John Logie Baird on This Is Your Life

Meanwhile the fortunes of the Baird family were improving. Diana completed her studies at Glasgow, and married in 1956. Malcolm became essentially self-supporting in 1957, with a research grant in chemical engineering at Cambridge. Margaret had emerged from her years in depression with a new philosophical outlook on life. Although she never attached herself to any specific religious faith, she claimed her recovery had been helped by religious teachings.

In July 1953, she attended her first public event since Baird's funeral, the unveiling of a plaque at Kingsbury Manor, where the Baird company had built its receiving and transmitting station in 1929. In October 1957, she was principal guest of the BBC television production, This Is Your Life, whose subject was Baird.

Among those who contributed to the programme were Moseley, Clapp, and Taynton. This is the only time the long-running series had ever featured someone no longer living. The programme closed with a tribute in verse by Christopher Hassall, poet, dramatist, and librettist, who had composed the lyrics for Ivor Novello's Glamorous Night in 1935.

Towards the end of 1957, the BBC asked me to supply all the information I had for their programme This Is Your Life breaking all precedents by producing a posthumous account.

Eamonn Andrews introduced all the characters, among them William Taynton, the first man to be televised, and Sydney Moseley. The cameras were brought right up to me at the climax, where I sat in a front stall, and Eamonn Andrews presented me with the scenario of "This is your life, John Logie Baird", in the form of a book.

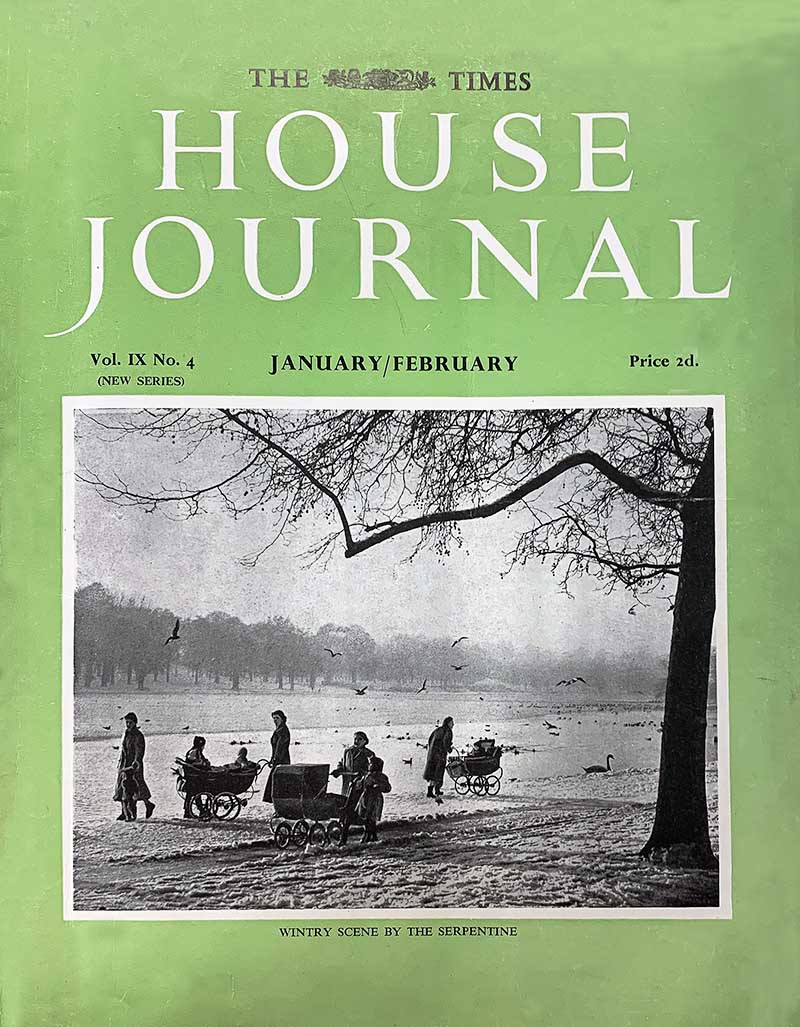

The Times House Journal January/February 1958

Appearances in Television Thirty Years Apart

By W. C. FOX

ALTHOUGH A VAST and abiding interest in all things chemical or mechanical, from the domestic electric bell to my father's new and rather mysterious typewriter, and taking in on the way my mother's sewing machine and any watches and clocks on which I could lay my hands, clearly indicated the desirability of a life work connected with mechanics and science it gave no hint of the strange happenings which might thereby turn up over the years.

Why I was made a reporter I could never understand, but, all that being accepted, it was perhaps quite logical and to be expected that when a rather untidy, quietly spoken, somewhat dreamy and vague young man turned up in Byron House, the headquarters of the Press Association in Fleet Street in 1925, saying he could see by wireless, that the new reporter, Fox, who was more interested in science and such things than in the solid and important subject of politics should be sent down to see him.

Baird and I found we had much in common and a sort of free and easy friendship sprang up between us, almost at once. So much so that from then on Baird, if he had any demonstration in mind, went straight to the P.A. and asked for Fox without for a moment considering the claims of other papers, scientific or lay. It was therefore quite natural that at the end of 1927 or early in 1928, when he was trying to transmit across the Atlantic to amateurs in New York, I should be present at this end of the line.

In those days amateurs were working on "short" waves of about 120-160 metres and to get across the Atlantic one had to transmit at a time when both sides were in darkness, roughly from about midnight to 4 am.

Experiments in Baird Laboratories

For weeks, having finished my sub-editing turn on P.A. General Service at midnight, I went along to Baird's new laboratories in Long Acre over a garage, and waited about until 4 am imbibing sundry sandwiches and beer, a most unsatisfactory diet after 2 am, to kill the time. And for weeks the results were always the same - "no reply," "fading," "distortion," "no reception," "break down" (of one sort or another) and gradually all the enthusiasts who waited, eagerly at first, faded away until at the end of January, 1928, only myself and a photographer were left!

Hard up for a "subject," Baird asked me to sit in for an hour or so. At that time only a portion of the first floor (his laboratory) was in use - a vast concrete floored barn of a place with long windows going right up to the ceiling. Temporary walls had been erected of hardboard, making cubicles and into one of these I was shown. It included one of the windows giving a view over the rooftops of London - at that hour, dark and grey with luminous patches and very mysterious looking. Everything inside the cubicle had been painted dead black and in one wall was a square hole scarcely a foot in size and closely around it were arranged some fifteen or so 1000 watt incandescent lamps.

One had to keep one's head not more than eighteen inches from the square hole and most unpleasantly near the lamps. The heat was intense and staring through the hole one saw nothing but a shimmering effect of darkness, produced by the outer edge of the rapidly rotating scanning disc. There was one other feature; there was an untidy litter or cables trailing everywhere on the floor and over the walls.

Well, I was sitting there, dreaming and wondering what they were seeing on the other side when Baird suddenly said "Wake up! You are more dead than the dummy. Move your head; wink; open your mouth; smile." Feeling as though I was operating cellar flaps and barn doors by means of thread I managed to achieve all that, only to be completely defeated by a sudden request to "Make a speech!" Think of it! Make a speech to a non-existent audience about nothing, in silence - we were only transmitting the image. My look of blank dismay must have been comic, for Baird roared with laughter and the fright (I had proper stage fright, all right) having been overcome, we went on for an hour and a half. And that took us to the end of the transmission for that night. Saying "good night" (it was about 5 am!) to Baird at our mutual street corner (we lived quite close to each other in those days) I asked casually "Any luck last night?" and received the quiet patient reply "We could not contact America all night."

Successful Transmission to New York

But we had been most disastrously (for us) successful. Baird's business manager was in New York to watch that end of affairs and walking in to the reception end about half way through the reception period exclaimed "I know that man, it is Fox of London" and as luck would have it a Reuter man was present, heard the remark, gathered such details as he could, and "told the world!"

The glad news reached London via the P.A., just about the time the evening paper sub-editors were making up the first edition and Baird and I had got off to our first, well earned sleep.

It reached me (almost as soon as I had got into bed, it seemed), when I awoke to the fact that my wife was shaking my shoulder and saying "Go round to Baird at once; he wants you." Three parts asleep I dressed and staggered round to Baird's attic and there found him on the edge of his bed, looking slightly bemused and a bit worried. He said "Perfect reception and you were recognised by Hutchinson. Long Acre (where his laboratory was) is besieged by all the reporters in London wanting interviews. What shall I do? I have warned them to keep the reporters there."

When I realised he had said nothing to anyone I used his phone - he had one in his bedroom - to speak to my Chief on the Press Association and, as soon as I announced myself, touched off the most concentrated hurricane of a "blowing up" I have ever had. There was nothing wrong which I had not done and the worst crime of all was that I had not lodged with the sub-editors a full and complete biography of myself with dates and other meticulous data.

When the temperature had fallen a little Baird and I put over an exclusive interview with at least a two-hour clear lead over everyone else and then we disappeared to clean up and get ready for the interview at Long Acre.

Neither of us had any breakfast that day or anything else till after 3 pm. It was one long interview with cameras clicking and flashing round us all the time. And of course, one or two papers which should have known better, in fact they were so called "technical" (they have since disappeared) followed the line of treating the whole thing as a spoof and challenging Baird to televise a group of perfectly stupid articles, to be recognised at a station a few miles away from the transmitter.

Towards the end of the day the papers began to be brought to us. I blush still and feel slightly uncomfortable when I think of it, for in paper after paper appeared my face sitting in front of the transmitter! And not only in the London ones, but practically every daily and weekly in the country! It was most embarrassing and I almost feared to go out, but most surprising of all, and probably many will doubt the truth of the statement, I did not make a single penny out of the performance, or get a word of thanks from anyone!

An Appearance Thirty Years After

And so we come to the second television appearance of "this witness," thirty years within a month or so later, and now only a week or so ago. Like the first it started quite innocently with a whole afternoon of questions about Baird by a BBC investigator. (They do not call them "reporters" there - they do not write shorthand!) Then a number of telephone calls over several days to clear up odd obscure points, ending with the casual remark "Of course you will join us for the transmission?" which brought me once again into direct contact with television. Within a week there was the preliminary reading of the script and drinking of BBC tea in the process, of our half-hour item - 27 foolscap sheets of it - to see if we agreed with what we were being given to say, and then a first reading against a stopwatch for timing purposes.

The next afternoon we all went to the Shepherds Bush television theatre for rehearsals and the "show." With us was Baird's first living subject, the office boy from "down below" at Frith Street, grabbed against his will by "that mad inventor upstairs" and thrust into an inferno of light and heat and strange machinery. No wonder he had been frightened and drew back out of the way. He was still a bit nervy, although now he had his wife and a daughter (as old as he had been when first he met Baird) to give him moral support.

There, also, was Baird's first engineer who was in charge of the South London amateur transmitting station on the night of the transatlantic transmission, and beside him Baird's old college chum and editor of the college journal, very hurt and angry because no reference was being made to Baird's considerable attainments as an engineer, his very successful college career and his literary ability, but quite failing to realise, stout friend that he was, that it was because Baird was all he said he was and a lot more besides, that we were all there.

Contrasts in Staging a Transmission

As to the transmission itself, thirty years had not made much difference and the similarities were much more striking than the differences. True, there was no apparent shortage of cash - we were in a theatre as against a hastily fixed up cubicle and there were uniformed staff to see that no unauthorised persons intruded and the staff, all told, probably ran into 50 or 60 persons: Baird and staff, including subjects on the transatlantic transmission, did not exceed half a dozen persons.

But for the rest there was just the same glorious tangle of cables everywhere, rather more so now for there were monitoring sets to enable one to look at one's self while actually "on" and the staff throughout the rehearsals were continuously bringing up new and better lights to add to the battery already pouring down on us. The scenery before which we acted or appeared was very much "home theatricals" and for me the saving grace was that the curtains behind the arch through which we had to walk were kept in place and made to hang properly by two bunches of rusty iron nuts, tied on, very casually, with string, and the producer kept coming behind and fiddling with them to get the curtains to hang properly. There was still the same strange feeling of appearing before and talking to "nothing" although we all knew the theatre was filled to the last seat in the back row of the gallery. We had seen the audience waiting in queues outside when we dashed out for a "livener" before the appearance, and again when, properly made up, we had peeped round the curtains. But when we made our entrance there was only a blinding wall of light beyond which there was nothing: there was the same old limit on movement and the danger of getting "out of the picture," but this time rather less rigid but replacing it was the need to stick to a given group of words - and, of course, some forgot their words, but Eamonn Andrews, the narrator, with a skilful question or so put that right and blunted the edge of anxiety.

In no time, it seemed, the transmission was over and we had foregathered for a modest little party. All who appeared had worked together with Baird in the past and there was much to tell.

For me, and I apologise for working so hard to wear that word out, the surprise was the number of people who were looking in and remembered, the next time we met, to comment.

Yes - this time I did get an honest halfpenny, but nothing like the vast sums some folk imagine are paid out.

My greatest satisfaction came from the fact that a modest, unknown, BBC scriptwriter had been the first and only person to recognise the fact, and had emphasised it, that mine was the first friendly voice Baird had heard in Fleet Street. What, I have often wondered, would have happened to British television if my answer to him had been as scantily courteous as all the others he had received in newspaper offices that day and he had turned away discouraged and let the matter drop?

Series 3 subjects

Albert Whelan | Colin Hodgkinson | Vera Lynn | Arthur Christiansen | John Logie Baird | Richard Carr-Gomm | Jack TrainEdith Powell | Anne Brusselmans | Norman Wisdom | Victor Silvester | Jack Petersen | Lucy Jane Dobson

David Bell | Matt Busby | Minnie Barnard | Gordon Steele | Louie Ramsay | Tubby Clayton | Daniel Angel

Anna Neagle | 'Dapper' Channon | Frederick Stone | Paul Field | Noel Purcell | Barbara Cartland

Harry Secombe | Archie Rowe | Humphrey Lyttelton | Francis Cammaerts | A E Matthews