Big Red Book

Celebrating television's This Is Your Life

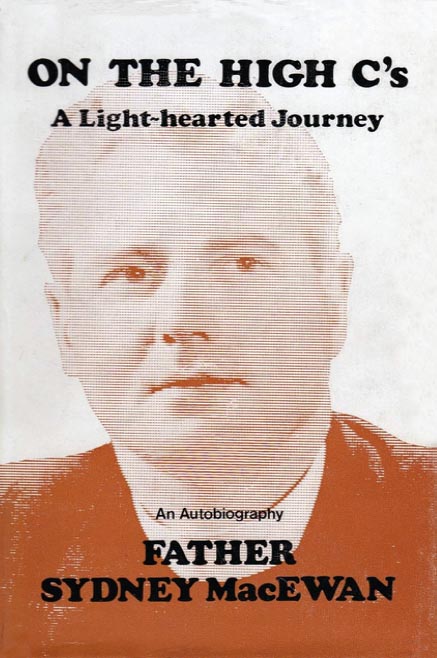

Canon Sydney MACEWAN (1908-1991)

THIS IS YOUR LIFE - Sydney MacEwan, priest and singer, was surprised by Eamonn Andrews during a religious conference at the Catholic Radio and TV Centre at Hatch End in north west London.

Sydney, who was born and raised in Glasgow, studied at Glasgow University, where he was encouraged by writer Compton Mackenzie to become a professional singer. Having moved to London in the early 1930s, he made several recordings for Parlophone, undertook two successful world tours, and by 1938, had become a star on the international circuit of concert halls performing traditional Scottish and Irish songs.

Despite his fame and success, Sydney followed his vocation to become a priest and began training at the outbreak of the Second World War. He was ordained in June 1944 and, having become parish priest at St Margaret's Church in Lochgilphead, Argyll, he later relaunched his singing career, recording and touring to raise funds for the Church.

programme details...

- Edition No: 198

- Subject No: 199

- Broadcast date: Tue 16 Oct 1962

- Broadcast time: 7.55-8.25pm

- Recorded: Mon 17 Sep 1962 8.30pm

- Venue: BBC Television Theatre

- Series: 8

- Edition: 3

on the guest list...

- Eric Robinson

- Harold - brother

- Roger MacDougall

- Sheila McNeill

- Mary Stewart

- Frances Boyne

- John MacPherson

- Sgt Michael O'Flynn

- Peter Ciarella

- Elizabeth Boyle

- Robert Wilson

- Jennie - mother Filmed tribute:

- Lily McCormack

production team...

- Researcher: unknown

- Writer: unknown

- Director: T Leslie Jackson

- Producer: T Leslie Jackson

celebrating the 'men of God'

Photographs of Sydney MacEwan This Is Your Life

I took my mother abroad a lot. But after her eightieth milestone, I thought, there may be no harm in a change of bed, but the business of aeroplanes and sudden temperatures of 80 degrees was perhaps no longer to be recommended.

So we chose to holiday in Dunoon that lovely Clyde resort that loomed so large in my childhood.

The second day we were there, my brother phoned:

"Keep it under your hat, Sydney - you're going to be on This Is Your Life. I thought I'd let you know."

This programme, run by Eamonn Andrews, was once the pride and joy of the British Broadcasting Corporation. It turned the spotlight on people whose lives were alleged to be that bit outstanding by way of achievement or courage or triumph over adversity or devotion to duty.

Its prime appeal was supposed to be that of surprise.

The technique was to inveigle the unsuspecting victim to London, where eventually Mr. Andrews proceeded to turn back the pages of life before his guest's shocked and incredulous eyes and the usual battery of high-wattage lamps and mobile cameras.

I had good fun for the next few weeks maintaining the Great Pretence. There were BBC photographers up taking shots of the village, and people stopped me on the street and said: "I wonder what they're up to?"

"It'll be one of those travel things," I said, hoping that my expression would not disclose that I wasn't a very good liar.

They were even buzzing around the mental hospital, doing interviews with the staff and discovering that I was one of the hospital's ministering angels - which was really a great exaggeration.

Even Bishop McGill was in on the plot. He told me one day: "Sydney, our man on the BBC Religious Board can't make it for the next meeting in London. You know the ropes - I wonder if you'd go down in his place."

This was really a testing moment. When he mentioned the date, it needed all my will-power to suppress a quiet smile.

Dear old mother had to go down as well. She was at the stage of not being able to realise what was going on. All that she could tell me was that she was off to London with my brother to visit somebody or other.

I suppose it was lucky for the BBC that, because of her age, she didn't have to live with the deceit. She just didn't understand.

Funnily enough, it was mother in all her innocence who almost blew the gaff completely.

They had her off with an earlier train than mine, so that we wouldn't meet. The BBC's concern was that I shoudn't be around London's Euston Station when she was met by their reception committee.

Unfortunately, mother's train was an hour late. And I understand that there were a number of nail-biting types at Euston, growing more and more convinced with the passing of the vital moments that the very worst would happen and our two trains would come in together at one and the same time.

They were saved the embarrassment by five minutes. The BBC's Catholic representative, Father Agnellus Andrew, met me at the platform and drove me to the Catholic Radio and TV Centre at Hatch End, where the religious conference was supposed to be taking place.

The whole charade began to amuse me more. I was chuckling inwardly. I lost count of the number of times I was tempted to say: "Wouldn't it be funny if I was on this This Is Your Life thing?"

Eventually Eamonn Andrews turned up at Hatch End with his inevitable book and that dramatic greeting of his: "Sydney MacEwan, this is your life!"

I was grateful for my brother's tip-off. It ensured that in front of the millions I was at least half-decently dressed!

It was bad enough being constantly labelled "The Singing Priest". To have added to this the nationwide reputation of the priest with the baggy breeks would have been rather unfortunate.

But I was left wondering how often has the secret of This Is Your Life really been preserved intact?

Could all the wives of those subjects who were husbands, for instance, have survived the agony of going around with sealed lips for weeks and even months?

I was part of this series, when despite its critics, it seemed to me to have an element of quality and dignity about it. It also achieved an essential versatility. Its characters were from all walks of life and some had brought to the world so much goodness and self-sacrifice that this mass exhibition of their virtuous example would certainly do no harm.

More recently as far as I can gather, the "secret dossiers" of Eamonn have tended to concentrate on various personalities of the show-business world.

I love stage people, but This Is Your Life has thereby got itself into something of a decorative rut. It also frequently runs the risk of developing into a mutual admiration society.

I was far from happy with what was alleged to be My Life.

Lily, Countess McCormack, was in it - and Robert Wilson and my brother, and my right-hand man at Lochgilphead, Peter Ciarella.

So far, so good. All splendid folk whose friendship I cherished.

But there was also a policeman who was supposed to have brought me up my haggis from the Glasgow Constabulary's Burns Supper. There were Sheila Craig, widow or Hector McNeil, and the playwright, Roger MacDougall whose only link was that we were contemporaries at university. Actually, I'd never met them again since.

They were presented as vital cogs in the wheel of my fortune, when the only real connection was that we each took part in the long, long ago, in one of those "College Pudding" entertainments at Glasgow University.

My Life had no Mannix, no Spellman, no De Valera or Arthur Caldwell. Not even the BBC's Andrew Stewart or Auntie Kathleen Garscadden, to whom I had been very close in the early days.

The whole thing came over as a trivial little cameo concerned with the life of someone who had certain experiences similar to my own. But that was as far as it went. I certainly never recognised it as my life. I hardly sensed it was dealing with me.

I remember as we walked towards the stage, Eamonn whispered somewhat apologetically: "Canon, you may be disappointed with this."

I'm afraid I was especially when it wasn't even a surprise.

He was accurate with his mode of address. I had received my Canon status at the age of 46, well ahead of a number of priests who were my senior. I was aware of no jealousy, however - of no grumblings at my having jumped the gun.

I took the award as a tribute to what I had been able to do for the diocese, not strictly an honouring of myself. That way I preferred it.

Series 8 subjects

Rupert Davies | Kenneth Revis | Sydney MacEwan | Cleo Laine | Arthur Baldwin | Edith Sitwell | Ben Fuller | Robert McIntoshMabel Lethbridge | Stephen Behan | Ruby Miller | Richard Attenborough | Daniel Kirkpatrick | Michael Wilson | Dick Hoskin

James Carroll | Uffa Fox | George Cummins | Hattie Jacques | Sam Derry | Finlay Currie | Phyllis Lumley | Ben Lyon | Bertie Tibble

Zena Dare | Victor Willcox | Learie Constantine | Phyllis Holman Richards | Michael Bentine | Joe Loss | Gladys Aylward