Big Red Book

Celebrating television's This Is Your Life

Lin BERWICK (1950-)

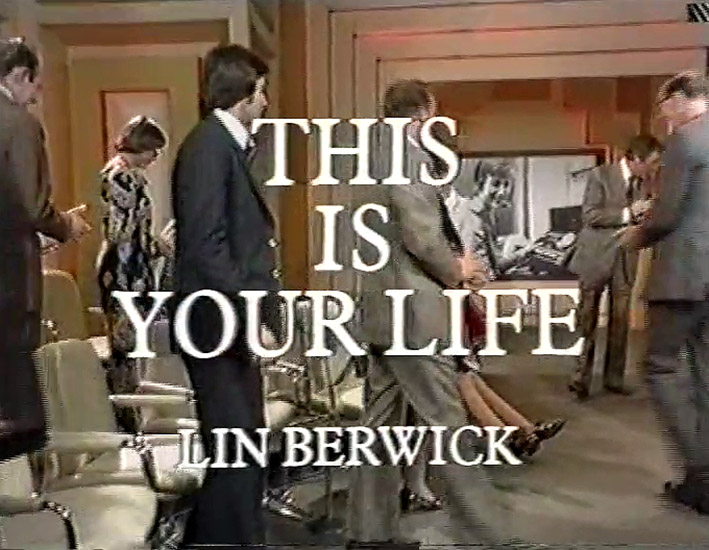

THIS IS YOUR LIFE - Lin Berwick, telephonist, was surprised by Eamonn Andrews during an office Christmas party at the Commonwealth Savings Bank of Australia in the city of London.

Lin, who was born in London with multiple disabilities, including Cerebral Palsy Quadriplegia, spent her childhood undergoing intense physiotherapy and various operations before taking her first steps with the help of sticks at the age of 12.

Despite her disabilities, and losing her sight completely at the age of 14, Lin trained as a telephonist and secured a full-time job, received a Special Achievement Award for work with the disabled and was the only disabled student in a scheme training volunteers as councillors to disabled people.

"Oh no! Crikey!"

programme details...

- Edition No: 472

- Subject No: 468

- Broadcast date: Wed 21 Dec 1977

- Broadcast time: 7.00-7.30pm

- Recorded: Wed 14 Dec 1977

- Venue: Euston Road Studios

- Series: 18

- Edition: 5

- Code name: Will

on the guest list...

- George - father

- Alma - mother

- John - brother

- George - brother

- Alfreda Elderfield

- Norman - uncle

- Jan - aunt

- Jenny Porter

- Fr William Sturks - via telephone

- Geoff Chandler

- Sid Crook

- Vince Simmons

- Les Kill

- Pete Brown

- Lin Preston

- Denise Colette

- Andrew Cruikshank

- Edith Taylor Filmed tributes:

- Hattie Jacques

- Muriel Braddick

related appearance...

- The Night of 1000 Lives - Jan 2000

production team...

- Researchers: Marilyn Gaunt, Maurice Leonard

- Writers: Tom Brennand, Roy Bottomley

- Directors: Royston Mayoh, Terry Yarwood

- Producer: Jack Crawshaw

- names above in bold indicate subjects of This Is Your Life

from domestic cleaner to teacher

a celebration of a thousand editions

The Daily Mirror reveal's Eamonn's This Is Your Life secrets

Magic Book That Opens New Chapters Of Life

TV Times feature on 'The Unsung Heroes'

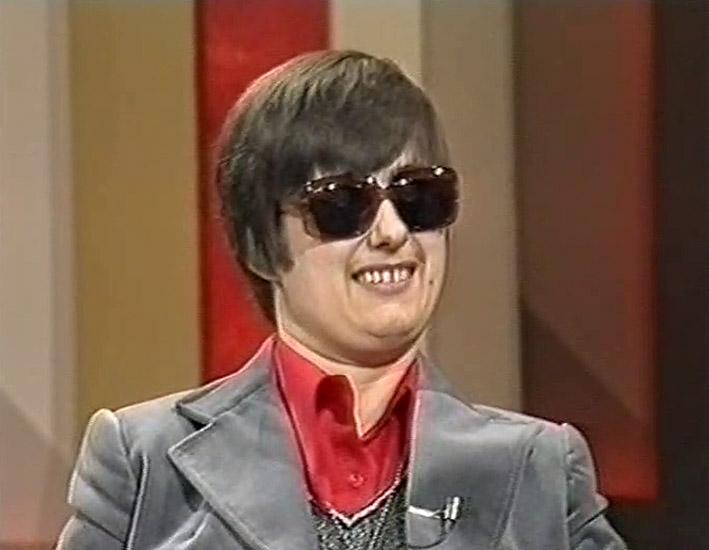

Screenshots of Lin Berwick This Is Your Life

It was the start of another academic year. I had been permitted to go forward to the next stage of my psychotherapeutic counselling training. This necessitated being released from the bank one morning per week, which the management happily agreed to. This time the lectures were held above a church in King's Road, Chelsea, and we were now getting down to some serious study of the different schools of psychology - Adler, Fromm, Freud, Jung - together with approaches such as transactional analysis and the techniques of family therapy. I loved every minute of it. I particularly enjoyed role play and psychodrama.

One afternoon as I was returning to the bank from the lectures, my manager, Mr David Wood, came into the switchboard room and said in his usual cheery way, "What are you doing on Wednesday afternoon, Berwick? I never know whether you are in or out these days!" I told him that I would be in the bank. "Good," he said, "because you are coming on a gin-sling with me." I told him to stop messing about and tell me what was going on. "Well you see, Lin, it's like this. You know the bank's policy of 'tell the staff as little as possible'? Well, that's it!"

I retorted by asking him to come clean, stop walking round in circles and rattling the bunch of keys in his pocket, and to stand still so that I could locate where his voice was coming from. "What it actually is, is that we want you to take part in a public relations exercise between the bank in London and our head office in Sydney, Australia. We're going to hold a Christmas party and we want you to be filmed making a call on the switchboard to wish everybody down-under a happy Christmas." I told him I had heard it all now and I wondered what else they could waste their money on, but of course I agreed to participate.

On the morning of Wednesday December 14, 1977, which was the day on which the filming was to take place, my mother woke me at 5.15 in the morning so that she could wash my hair. I told her I thought this was ridiculous. She said that if I was going to be filmed wearing headphones without my hair being set it would stick up and look awful. I had a splitting headache and hardly felt I could be bothered, so she said "All right, get back into bed and I'll tell Mr Wood you can't help him". I felt I could not let that happen, so I agreed to have my hair washed. Mother had told me she had taken that day off to do some Christmas shopping as she did every year. The night before she had, as far as I knew, been to the annual Christmas dinner and dance at the bank where my father worked. So, spruced up and ready for filming, I arrived at the bank at 7.45am, only to have the awful experience of one of my tripods snapping in two. It had snapped because of metal fatigue. I telephoned my mother in a panic and a spare pair was brought to the bank. Later that morning I was told a huge white van had pulled up in the road outside the window of the switchboard room and on its side were printed the words "Australian World News" Later that day, food and drinks and Christmas decorations were delivered to the bank and at three o'clock, when the bank doors closed for business, the whole banking area was transformed into a party scene. At 3.30 I made my way up the second floor for my usual toilet stop and was surprised to find the bank's senior secretary accompanying me, chatting as we went. At four o'clock a group of people gathered in the brightly decorated banking hall and a chair was brought into the midst of the group where I was placed so that I would feel comfortable. I was offered a sherry, but declined as I was not allowed to take alcohol with my medication. Then David Wood said "Well, just hold it so that you look as though you are enjoying yourself for the publicity film".

The party was getting under way when suddenly the bank doors opened and a squeal of recognition made me realise that something exciting was going on. Suddenly, I heard a very familiar voice. It was Eamonn Andrews saying "Hello, Assistant Manager David Wood". Although he is English, David gave him the typical Australian greeting of "G'day". I found myself thinking, "Oh, no" and saying to myself "Don't be ridiculous, he's probably come to surprise one of the Australian cricketers who bank with us" - yet a moment later he was at my side, saying "It's my pleasure, because I can say to a very remarkable young lady, Lin Berwick, tonight This is your life". There was much cheering and laughter, but my knees had gone to jelly. Then I heard Eamonn saying, "All your friends here are invited back to the studio". So this was what the public relations exercise had been about! That dinner dance which my parents had gone to the previous evening, and the shopping trip that my mother had done, were in fact rehearsals at Thames Television studios for this surprise. Although they did not know it, the people at the party in the banking hall had been selected by my mother because they had helped me in some way or had been a friend during my time at the bank. I said to my father "You rotten..., now I know why you bought a new suit!". This was not shown on TV but certainly caused much laughter. What a wonderful and totally unexpected Christmas present! I was so overcome by it all that I literally couldn't stand up. My father picked me up in his arms (I was much slimmer then!) and carried me to the waiting seven-seater Daimler limousine which was waiting outside. A huge crowd had gathered around the building as they recognised Eamonn, because they expected to see someone famous appear. Instead they got just an ordinary working-class girl from the East End of London who couldn't even stand up on her own two feet!

Eamonn was very kind and attentive. He kept asking me how I was feeling as we drove to the studios in Euston Road. He was concerned because he thought I looked unwell and when I told him that I felt sick, he opened the windows to give me some air.

On arrival, I was taken to the VIP room where I was locked in. This was done so that none of the people who were to participate in the programme would be able to call into the dressing room and spoil the element of total surprise. I asked to see my mother but was told that would not be possible. By now I was feeling bewildered and totally disorientated by the emotion and by the surroundings which were unfamiliar. I said if I couldn't see her, I would refuse to go on. She was brought to me without any further delay. She was laughing and crying all at the same time. Though it added to the excitement, the need to keep it an absolute secret had been quite a strain. If I had discovered what was going on, even just minutes before it began, the programme would have been scrapped. My parents, in fact, had known about the plan for some six weeks, although Thames Television had been researching it for almost a year. It had all started one night when Dad received a call from a Thames Television researcher. He was asked whether I was at home and when he replied that I was, he was asked to go outside and speak from a public telephone. I was upstairs in my study and Dad had taken the call downstairs. My mother instinctively knew what they wanted and said to my father "If they want Lin for This Is Your Life, the answer is 'No'." She was apprehensive about our personal life being portrayed on television, particularly on a programme which she thought might sentimentalise it, something which she knew I would hate. Dad told her not to be so stupid, that it couldn't possibly be for that. Mum told me later that when he came back to the house he was as white as a sheet. "You were right, you know," he said. "You did say no?" Mum asked. "Of course not." he replied, "if the nation wants to pay Lin a tribute, who are we to say no?" So that was how it had all begun. And now she expressed a sense of relief that there was no longer any need for secrecy. But I was feeling terrified and overwhelmed by what was happening. My stomach was somersaulting and I had to ask Mum for a valium.

There was a great deal of activity before the show began. I had to undress and have a belt placed round my waist on which were mounted two batteries and a long length of cable which was threaded up through my clothing for the microphone which was put on the lapel of my jacket. Then I was seen by the make-up department and before I knew it two and a half hours had gone by since the time Eamonn had spoken those magic words. It was planned that I should go onto the set in my wheelchair, but I wanted to walk because I felt that this was something worth struggling for. So Eamonn came into the dressing room and practised guiding me up and down. We then walked to the back of the set where my mother was waiting in the wings to help me up the high step. By this time the film of the "pick-up" was being shown to viewers. Eamonn asked me how I felt and gave me a reassuring hug. He started the countdown. Ten, nine, eight... and suddenly he said "Three steps forward and then turn right". Although I had to walk slowly and carefully because of my new sticks, I got to the chair on the set without any problems. I was in front of the cameras and there was no going back.

What the viewer sees is what actually happens. There is no editing on this programme. It was for me a very moving experience, and I felt deeply privileged that I should be given this honour. Thames had gone to a great deal of trouble. They had driven a Belgian priest friend of mine one hundred miles through the Pakistani jungle so that he could talk to me on the telephone. They brought family and friends from many parts of England, and even flew a friend over from Australia whom I had never seen before. She was the sister of an Australian friend who worked at the bank and she had sent me tapes to tell me about Australia and the family there. Thames brought her six months old daughter Rebecca over too so that I could have the pleasure of meeting the child. They also brought over a very dear friend of mine who had gone back to her home in Canada. Andrew Cruickshank and the late Hattie Jacques were also on the programme. Hattie spoke on film. She had known me very well as a child because she had been President of the East London Spastics Society. My dear friend, Andrew Cruickshank, was the President of the Disabled Fellowship Club of East London and naturally wanted to support me on this special occasion.

After the programme, I was taken into a small anteroom where champagne was on hand for me and my immediate family so that we could enjoy the opportunity of a few private moments together before we were taken to a large reception that had over three hundred guests. The guest list also included family and friends who had not been on the programme and all the people who had been interviewed together with all the people from the bank whom my mother had selected. So that "boring public relations exercise for the bank" had turned out to be something quite spectacular!

After greeting our guests we were all invited back into a theatre to watch a film of the programme. It was really quite amazing because at the time I was completely numb and almost unaware of what was going on around me. It seemed really strange hearing it all over again. Before the programme had started, Eamonn had told me that it would be seen by very many people. Afterwards he confided that it would be seen by 30 million viewers! To me that was absolutely mind-blowing. When we had all recovered from the shock of seeing how we were going to appear to the television viewer the following week, we had a wonderful party. Everything possible was done to make this night a happy one, even to the extent of a beautiful bouquet of scented flowers for me.

Just after 11 o'clock I decided that I needed to go home. It had been an extremely exciting day, and one I shall never forget, but I was beginning to feel totally exhausted. Mr Wood had given my mother and me a holiday the following day to help us recover from the excitement. We really needed it! A few days later the letters from viewers started to pour in. They were from all over Great Britain and Ireland. Many had found the programme inspirational, particularly those who were struggling to cope with some kind of adversity. We can never quite know how what we do and say will affect someone else. With television the effect is immediate and the ripples from it go on for a long time.

When Eamonn hands you that famous red book at the end of the programme, it is just the leather binding with his script inside. The completed book was delivered to me by chauffeur-driven car some three months later. It contained photographs from the beginning to the end of the programme. Most of the photographs are in black and white although some are in colour. The text of mine is compiled in print and in Braille and there is a sound recording on disc. (Not many people had videos in those days.)

There was something very special about Eamonn Andrews. On the day of the programme he had had the ability to make me feel that I was the most important person in his life. He wrote a personal letter of thanks in the famous green ink, which was his trade-mark and we continued to keep in touch until his death. This Is Your Life is synonymous with Eamonn Andrews, and I feel that the programme should have died with him. No-one will ever be able to take his place, however well they might do the job.

That one single programme reached more people than I will ever know and for that reason I thank God for it.

Series 18 subjects

Richard Beckinsale | Peter Ustinov | Virginia Wade | Robert Arnott | Lin Berwick | Bob Paisley | The Bachelors | David BroomeArthur English | Barry Sheene | Margot Turner | Pat Coombs | Michael Croft | Max Boyce | Nicholas Parsons | Richard Goolden

Ian Hendry | Marti Caine | Ian Wallace | Dennis Waterman | Anton Dolin | Terry Wogan | William Franklyn | Richard Murdoch

Harry Patterson | Jule Styne | Mike Yarwood